|

REMINISCENCES

The Henry Luce Chapel on the Mae Kao Campus of Payap University in Chiang Mai, Thailand is, as it was planned to be, the identifying structure of the university. The chapel was constructed with a generous comprehensive grant from the Henry Luce Foundation at the urging of the United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia (UB), also a major beneficiary of Luce funding. One stipulation of the grant was that the university must choose from a list of architects of international renown provided by the foundation. For example, Tunghai University in Taiwan chose I.M. Pei. Payap University requested the services of Ed Sue Associates of Oakland, California, based on his experience in Asia, including his accomplishments in Hong Kong and a year he spent in Thailand as a teaching volunteer at Bangkok Christian College. Ed was told that the building should clearly be “Christian and Thai”. He succeeded in designing a chapel that is “Christian and modern”. From 1974 to 1983 Payap College was located on two in-town campuses. During that time undeveloped land was acquired east of the city through a grant from the American Schools and Hospitals Abroad program of U.S. Aid for International Development of the United States State Department. As that land and four buildings were being readied for occupancy, Dr. Amnuay Tapingkae, first President of Payap (1976-1985), learned of the Luce Foundation program to provide chapels for UB institutions. Dr. Konrad Kingshill, Vice President for Development, was assigned to work with Ed Sue to see the construction through to competition. Move to the Mae Kao campus, completion of the Luce Chapel, and Payap College’s elevation to university status all happened in 1983-4. Main features of Ed Sue’s design were energy efficiency, flexible utility, classical elevation of attention upward, and a sense of community intimacy reflecting the theological mood of the 1970s. However, the building, Ed told us, was also to evoke the image of a lotus on a lotus pond. The chapel was built in the middle of a small pond, accessible by an imposing bridge. Ed insisted that accomplished the mandate to make the chapel “Thai”. The chapel was made of concrete pillars and pilings that managed to be both substantial and spacious. From the outside the main feature is the roof and a steel and glass tower suggestive of a spire surmounted by a tall cross. In fact the entire structure was attached to a pyramid of 4 massive concrete beams meeting high overhead in the center of the ceiling. A second implied pyramid fractions the roof lines and rationalizes peaks in the cardinal directions. From inside, the space appears to be a wide flat floor with a sunken middle area and a geometric bowl above. Seating for 500 is on three sides of an octagon that dissolves into a square in the center. The fourth side, opposite the main doors, is a platform on 2 levels. Seats are on steps descending toward the center. Under each seat, at the back, is a vent so that cooler air from the water below rises up and is deflected through louvers in the tower. Furthermore, walls on 3 sides of the room are simply shutters, allowing maximum ventilation. Ed’s intention was for there to be little need for air conditioning, artificial lighting during the day, or sound amplification. He succeeded with two out of his three goals. (Acoustics are bad inside, since the bowl-shaped pond below and the bowl shaped ceiling above focus outside sound in the chapel.) The lower floor is covered with teak parquet. Furnishings, including pews, are teak. The heaviness of the stark concrete beams is mitigated by substantial lighting fixtures of teak that seem to float in mid-space, repeating the horizontal lines of the teak seats and horizontal alignment of the shutters all around the walls. The visual effect is white vertical lines and ceiling leading upward to a clear glass tower with a view of heaven above, and earthy-brown horizontal lines on three planes. Furniture consists of the pews attached flat to the concrete steps, a large pulpit and smaller lectern, and a communion table, all of teak. The “chancel” furnishings are moveable to allow for various arrangements, depending on occasion. Mrs. Josephine McLean, an artist from New Zealand who spent a decade with her husband at Payap, designed bas-relief wood carvings for the pulpit and lectern and for a pair of double front doors, each with a set of traditional symbols with Thai flavor, representing the four Gospels. The first worship service in the chapel was in 1984. It was refurbished last year, after 30 years of use, by a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation.

0 Comments

I have spent my life listening to the sounds of Christianity crumbling. Creak, crack, crunch … chunk by chunk the world-wide church is splintering first here then there. Nothing world-wide will withstand the collapse in the end.

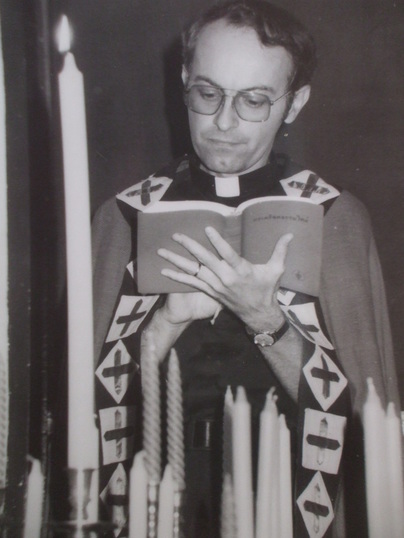

I hasten to say Christianity is growing. Membership is increasing and there is not the least reason to believe this trend will falter. It is the world-wide-ness of Christian organizations that is ending. That is what I find sad – and disappointing because I felt recruited for and called to a role as a Presbyterian in helping the Ecumenical Church grow. [The picture accompanying this essay is from 1980 at the crest of my expectations for the world-wide church.] This week it is world-wide Anglicanism that we heard cracking. The North American Episcopal Church has been formally “suspended” from world Anglicanism. The idea that there is a world-wide Anglican community is now in jeopardy. Episcopal bishops and the presiding bishop (the North American primate) no longer have a voice or vote where it matters in Anglican councils. Unity is a lost priority. When I was a seminary student in 1962-1965 I was closest to Dr. Lew Briner at McCormick Theological Seminary. He was one of the Presbyterian observers at the Second Vatican Council. Heated by hopes raised in Rome, a first step toward reunification was to unify forms of worship built around a “Common Lectionary” patterned on liturgical reforms of Vatican II. We Protestants would raise our worship forms as Vatican II was modernizing Roman Catholic liturgies. We would meet them in the middle. Meanwhile, Protestants in North America, Canada, Australia and India (and nearly everywhere) developed united, re-united, or uniting churches. An ongoing Consultation on Church Union helped member denominations in the USA design worship books and plans for merger. There was enthusiasm for forms that would be compatible world-wide. As Dr. Briner’s enthusiastic protégé, I drafted a worship textbook for our seminary in Thailand based on the concept that worship would soon be what was being discussed in Rome and in all branches of the World Council of Churches. If Evangelicals didn’t want to get on board this fast-moving band wagon they would be left behind. Then Rome balked. The common lectionary was rejected. The Roman Catholic Church decided not to revise the calendar of readings very much. Before long, unification actions were outnumbered by splits and defections, small at first but then much larger. Simultaneously, former mission churches achieved mature independence, not only with regard to funding and leadership, but independence of theology and tradition based on “relevant history”. Few of these emerging mission and independent churches and movements wanted anything to do with unity. The Ecumenical Movement was going to have to be sustained by older churches, but then the compelling reasons for making the effort began to fade and at the same time revolts began to fester. The united, world-wide missionary effort faded, and with it went the idea that it is better to work together than to build churches competitively. Every couple of decades brought a new cause for revolt: feminist issues (e.g. women pastors) split churches, presumed communist leanings or social liberalism aggravated large sectors, and now we have gender and sexuality as a presenting issue for further fractures. During these decades of decline in the hope for detente and reconciliation I have become convinced that Christian church leaders have been myopic about what it is all about. As recently as yesterday I read an Anglican scholar’s summary of the decision in London, saying that it is all about conservative Southern Hemisphere versus liberal social views, as if this is exclusively a church issue. We have all talked about church schisms that way. It’s the church splintering over something, of course. So we look no further. Now I want us to look again. The trend has been toward cultural localization all over the world at the same time as there is economic globalization. The “issues” leading to revolts have supplied energy to incite separatist action, but the ISSUES behind the issues are the same pressures that have split countries, ended empires, divided societies and accelerated ethnic eradication efforts beyond counting since the end of “World War I/II”. I believe THE ISSUE springs from a crisis of identity and meaning. The more economic globalization there is the more cultural localization emerges. The name of this localization is tribalism. It is on the rise again. The two years following the Battle of Hogwarts were very hard times for many a magical household. That was especially true for families who had lost members in Voldemort’s year back in power when Death Eaters and bands of Snatchers rampaged the magical world trying to purge all Muggles and Mudbloods.

Few were more hard-pressed than Tira Kitner and her granddaughter Maggie. Both of Tira’s sons had been killed along with all their families, sparing only little Maggie who was now ten. They had lost everything. They survived in a highland hut above the village of Gilfenning, just a fair broom-ride from Hogwart’s Castle. As the shortest day of the year passed and Christmas came and went, the weather grew more severe. Maggie was now old enough to share her grandmother’s struggles as well as anxieties that the dour Scottish matron did nothing to hide. Of the necessities for winter they had little, little oats for porridge, hardly enough wood for the fire to last another week, none of anything else. Then began first bright glimmers. A few days before Hogmanay two people from Gilfenning made their way up to Tira and Maggie’s hut with a proposal. “We are going to revive the ‘old way’ a wee bit,” they explained. For years Gilfenning was one of the few places in Scotland to end the year with the burning of the Clevie. To that custom they wanted to add another vague tradition from the distant past. “Make us a Sun Goddess, will’ye?” Ailie Gordon asked. Maggie was mystified but Thira was alarmed. Anything that drew attention to the ‘old way’ was going to arouse suspicions. But Ailie produced a picture from the Inverness Courier of “the Catalonian Sun Goddess” used in a Hogmanay parade in Edinburgh. “If they can do it down there, we can do it up here,” Ailie declared. The picture placated Tira a little, but she said, “Why do ya come ta me?” She tried to keep the fact she was a witch a secret. Had they found out? Was trouble on the way?” “Who knows the old ways better?” was the only answer Ailie would give. “Tell us what you need.” “Just some flour for paste and some strips of cloth.” Ailie and her friend left a bag of oatmeal “as a down-payment”. Within two days the sun goddess image was ready for delivery. Meanwhile, preparations were underway for the burning of the Clavie. An oaken whiskey barrel was sawed in half and securely mounted on a pole. It was split apart and stuffed with twigs and splintered wood doused in coal oil. As far as the villagers knew this was just one of many ways of sending off the old year with fire. In other places burning balls were hurled, torch parades were held, and bonfires were set. In larger cities fireworks were colorful. Some brave and foolhardy fellows breathed fire or twirled spectacularly burning batons. The Clavie was spectacular enough for Gilfenning. After it was lit, the parade wended its way to the top of Gilfenning Ridge led by three strangely dressed sisters carrying the Sun Goddess. The whole parade could be seen from Tira and Maggie’s hut, but Tira merely stood in the shadows and huffed at this imaginary magic. The ruckus was still going on when Tira and Maggie were startled to hear a male voice call from the path to their door. “It’s a brigand!” Maggie squealed. “Brigands don’t announce their coming,” Tira retorted. “But if it’s after midnight it’s our ‘first footing’! Light the lamp and see who it is.” At Maggie’s invitation a tall dark man stepped into the circle of lamp-light. He was followed by two younger versions of himself, all dressed for the chilly New Year’s night, not in tartan wool but distinctly wizardly attire, complete with peaked hats. Tira held her breath. Yes! The first foot across her threshold on Hogmanay night was a tall dark man. Their luck had turned! Tira could hardly keep from smiling. The dark stranger said not a word but set a bag on the table in the middle of the room before waving a stick in his hand at the glowing fire in the hearth causing it to blaze brightly again as if an armload of kindling had been thrown on it. One of the pair with him unpacked the sack, bringing out a bottle of whiskey (not the local Gilfinning kind, a mellower brand in a triangular bottle with a name that was very well known). Then came a ‘black bun’ stuffed with rich candied fruit and sweetmeat, a small symbolic sack of coal, one lump of which the other young wizard tossed onto the hearth producing a magically warm, multi-colored flame that would go on burning throughout the winter, and a heavy package of shortbread. Tira was beside herself. Not in decades had she seen such an auspicious thing as this first footing and set of gifts, and never had it happened to her. These were the traditional Hogmanay promises of a prosperous New Year. “I would not object to a slice of the black bun,” the tall man hinted, removing his hat. In better light, he was seen to be younger than Tira had first thought. Maggie scurried to cut the bun into six pieces for the five of them. Tira regained her wits as well, and opened the tall green bottle, tipping a splash into each of the two glasses she owned, offering one to the stranger. It was such a night and such an occasion that normal social formalities were foregone, but not forgotten. Tirathought of asking the names of the visitors and all the customary banter to become acquainted, but it felt wrong to interrupt this quiet event that seemed so fraught. Laughter and cavorting on the ridge were still going strong, but it no longer intruded into the hut where the dark stranger said, “Now for the last piece of the black bun,” as if it was special rather than simply left over. He handed it to Maggie. She was unsure what to do with it. Her hesitation ended when she was told, “Eat it carefully.” The reason was immediately clear when her bite produced a substantial gold coin. There were three others in that slice. “Now, two final things,” the stranger said. “Do you know of Hogwarts?” “Maggie misunderstood. “Tonight is Hogmanay,” she said. “Hogwarts,” the stranger repeated. Maggie lapsed into embarrassed silence. “It’s the witch school,” Tira replied, making it clear she had not been there. “I am a graduate, a year ago. My name is Dean Thomas and I have news. Next month you will be eleven, Maggie,” Dean said, as if Maggie might not know. “On September first I will come back here to take you to Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, if you would like to go.” Rather than pleased, Maggie was alarmed. “Oh, I cannot leave Grandma here alone,” she protested. Dean smiled for the first time. “Tira Kitner, your wand has been recovered from the scene where your family was massacred.” He drew the knobby shaft from his sleeve. “And with this and the help of these two,” he indicated his helpers, “you will produce brooms.” Thea did not need to be told what kind of brooms. It had been the craft of Kitner women all the way back to Poland. Tirastreaks would soon be the most sought-after magical brooms in Europe by those who could afford one. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed