|

On Christmas I “joined” the congregation of the Washington Cathedral for their midnight Eucharist at which the Episcopal Bishop of Washington DC, the Right Reverend Mariann Budde delivered the Christmas homily. It was inspirational, insightful, and interesting. It “worked,” I thought, reverting to my seminary-teacher mode.

But why did it work? Why do some sermons work and others do not? This is a question I pose not only for Christian preachers but for Buddhist and other preachers, as well as those who listen to preaching. There is one absolutely indispensible component for a successful preaching event: the listeners must be imbued with the foundational narrative as it relates to their existential context. In this case, the congregation in the cathedral and on-line (as was I) must know the Christmas story and find it currently and personally important. There is a link the preacher must make between the story that people know and how it relates to what’s going on. As to the Christmas Story, we Christians have that memorized. We know it by heart, at least the outline. It’s about Mary and Joseph going to Bethlehem, having trouble finding lodging in the inn, birthing the baby Jesus in an animal shelter, shepherds hearing angels singing and visiting the holy family, and then three wise men (kings?) on camels seeing a star and coming to worship the new king they have read about, and then evil Herod trying to kill the baby but Joseph taking the family and escaping to Egypt in the nick of time. The story can almost be taken for granted, as long as the audience is familiar with it. Christmas worship can then safely include symbolic references to the basic story. A star hanging from the rafters of a cathedral or stuck on top of a Christmas tree needs little explanation. Plaster sheep or children dressed as shepherds fit into the picture. Songs create a familiar emotional tone. Nevertheless, there are levels of meaning that can be explored … or not. Many Christmas services and most other Christmas events do not explore very deeply beneath the surface. Oh, there is a predictable anguish about how the real meaning of Christmas has been diverted by Santa and by commercialism. We try to get back to that real story with our candles and carols. But if the story is to be successfully probed for deeper meaning (that is, if the sermon is to “work”) it must connect the dots between what happened in Bethlehem some 2020 years ago and what’s going on right here and now. Bishop Budde’s homily was a splendid example of how to do it. She began by reminding everyone of Dietrich Bonheoffer’s heart-rending Christmas letter from prison to his family. She mentioned, then, her main point, that there is always a gap between what is and what could be. We feel that keenly on Christmas, but Christmas addresses that, because Christmas is all about a growth of awareness that God dwells with us. The STORY, she reminded us shows this gap, and how God comes to us to deal with it. The gap is seen in ourselves where we know we are not as we could be. It is in our family circle where there are divisions. In our community life we are polarized – ah, now she is particularizing a social condition. At the end she expanded her application to the whole world. Her sermon was pastoral, befitting her office whose symbol is a shepherd’s staff. It was not prophetic, denouncing the causes of the gap, but persistently announcing the solution as the main fact of Christmas. When speaking to people who know the Christmas story, it is expected to go deeper into what it means that God has come among us. Christmas is the beginning point and the ending point of the Bishop’s sermon. It was the context and the content of the whole service and what had brought the congregation to fill the National Cathedral at midnight. The sermon “worked” because the issue of gap and brokenness which is both universal and particular is consistent with the Story as everyone thinks of it. “Yes,” we respond, “there certainly was a gap between what God was doing in Bethlehem and what the government was doing.” And there still is this gap between what God is doing with Jesus and what governments are doing. What would it be like to preach on Christmas to a congregation who did not have the shared narrative of Christmas instilled in their minds? I have done that. In that case the homiletical task is quite different. Without Christmas as the unifying context and without the Christmas story to build on, the elements of a typical Christmas remain fragmentary and attached to individuals’ random and diverse meanings. The dots stay mostly unconnected. Most preachers would probably begin by introducing the Christmas story. “Christmas is the celebration of the birth of Jesus.” The idea would be to expand the audience’s knowledge, in hopes that some would “catch” or remember something. Maybe the benefit would be bridge-building between the audience and Christians living nearby. Preaching a Christmas sermon to a non-Christian audience would be a long-shot. It is hard to make it “work” at a deeper level because the audience does not have “the foundational narrative.” It is the same reason that tourists in Thailand tend to miss the whole point of a Buddhist sermon. The narrative context is missing for them as well as the social context. A Buddhist sermon loses a large part of its purpose if the congregation does not imagine themselves to be an extension of audiences who gathered to implore the Buddha to tell them how to overcome suffering. A Buddhist preacher will be most successful if the audience is a cohesive community and the preacher is an integral part of it. Most Buddhist funeral sermons, for example, assume that the fundamental story is shared by everyone, and that what is needed is an interpretation of how to overcome the multiple anxieties that death arouses. Both the sermon and the funeral event combine to do that. It is not strictly necessary for a Buddhist funeral sermon to be intellectually stimulating, or even fully understood. Some sermons are mostly chanted in a way that the congregation simply knows “that’s good, it’s just what it’s always been.” Anxiety subsides. A Christian Christmas celebration works that way to some extent. It is not strictly necessary for there to be a sermon. A cantata or pageant can renew the narrative. The Eucharist is supposed to do that surpassingly. The sermon is only successful in a context of understanding. Life is messy, but there is help nearby. The whole worship event communicates “it’s going to turn out well.”

0 Comments

REMEMBERING CHRISTMAS OF 1989

Preface: The week before Christmas in 1989 after the Berlin Wall came down and Eastern Europe felt velvety and joyful, the bloodiest revolution of all raged in Romania. Then, on December 22, it seemed it could be over, but the news was slow to reach into the mountains. A fine dusting of snow filtered down on the village of Borsa-Dej. Pastor Laszlo gazed out through the diamond-shaped panes in the windows of the parsonage wing of the Reformed Church. His breathtaking view of Mount Pietrosu was almost obscured by the flurries. In this Carpathian valley every winter day was nearly always overcast, and the weather every Christmas Eve was ominous as well – as was the outlook for the days to come, because Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, and every day, were days of stifled dreams and repressed ambition. The sheep herders and timber cutters of Borsa-Dej had never known anything else than being under the iron fist of the Ottoman Turks, the Nazis, and then the Communists. For four decades the Christmas Eve service was the only time the Reformed congregation ever dared to gather, except on Sunday morning. And for two of those decades, every Christmas Eve Pastor Laszlo watched from his pulpit as Nicu Hoge stood in the back corner of the sanctuary taking notes on every word the Pastor said, and carefully recording who came to church. It was as if the two of them, at opposite ends of the room, were on opposite sides of Borsa-Dej, one a communist representing hostility to religion, and the other a Christian pastor, representing a holy mystery that somehow threatened to destroy political oppression on a night like this. There were too many candles, and too much singing of angels and of God, for tyranny to stand it. “Comrade Nicu, in your report tell them how the Christians of Borsa-Dej love Jesus,” Pastor Laszlo had said last Christmas Eve as the informer had brushed past him on his way out of the church building. But this year the snow flurries were lighter than usual, and even the faint silhouette of Mt. Pietrosu was briefly bathed in an orange and lavender glow from the setting sun, as Pastor Laszlo allowed himself to be transformed by the wonder of the events of the last week. Most of the time their remote village was ignored by the powers that played games in distant cities, but, Pastor Laszlo well knew, at least by the time the snow-packed mountain passes had melted in the spring, some effects of their maneuvers would drift up to Borsa-Dej. How long would it take this time, Pastor Laszlo wondered, for the tremendous news he had heard over the static on his radio to make this latest change felt in their remote valley? And what would be the first sign of the change? On his lap a tattered Bible lay open to the words from the Christmas story, “And on earth PEACE….” It was the need for peace that sent tears streaming once again down the pastor’s cheeks. News had come of the slaughter of children and innocents by the hundreds. Even there in Borsa-Dej, where they had never seen an army tank, Pastor Laszlo could imagine the sight of their firing down a street filled curb to curb with people carrying flags. “What flag?” he mused. The national tri-colors … with the communist emblem snipped from its center, as if it had been ripped out by one of the tank’s bullets on its way into the crowd. Pastor Laszlo imagined the scene, mist in his eyes, as mist began to enshroud Mount Pietrosu. He envisioned, too, how the soldiers would have been sent around the public square to toss the dead into trucks like cord-wood to be dumped into a ditch and covered by a bull-dozer. Finally, Pastor Laszlo formed a picture in his mind of how his fellow pastors in less remote places must have been attacked over the last few weeks of the hideous crack-down. Some of them must have broken legs and burnt skin that results from an interrogation by the secret police. The revolution, after all, had first broken out in a Reformed Church in Timisoara. As the grey-green forests grew dark outside Pastor Laszlo’s window, the faces of Elena and Corneliu Ratescu floated into his memory. This very night marked the second anniversary of their disappearance. Such a happy couple, Laszlo thought, the brightest and best of Borsa-Dej. That is, of course, why they were sucked into the mindless bureaucracy of government service and relocated far from their beloved mountains. It was the government’s prime ploy to rip people out of the places they love, and apart from the people they love, and into settings where they are helpless and forced to live with people they do not know. Even so, the spirit of such a couple as Elena and Corneliu was not so easily extinguished. For five years, they almost flourished as accountants and shift managers in a factory producing farm equipment to harvest hay. Their work, they wrote home, reminded them of the mountainside hay fields in the Carpathians near their village. And the people with whom they worked, they reported, also had spirits, once you got to know them. Such spirits, evidently, drew them into church on Christmas Eve where they were neatly set upon by the police. For two years there had been only silence. Whatever had happened to Elena and Corneliu Ratescu could well become the stories of all the souls of Borsa-Dej, they thought last Christmas Eve. Village after village was being relocated into urban concrete apartment towers, layer on layer, like bees in hives. The government, of course, cast no thought to the matter of their village relationships, their love of the mountains bred in over a thousand years of living there, nor their native devotion to the Lord God and the stone church in which every important event of their lives was celebrated. One by one, already a thousand or more villages had been abandoned and then leveled so the people could not be tempted to return. But, if the incredible bits and pieces Laszlo heard over the radio proved to be true, all that might be over. It was being said, if he heard correctly, that the nightmare of the dictatorship was ending. There was even news, now, that in a dozen other countries vast changes were sweeping out tyrannies and letting in the wind of freedom. Pastor Laszlo breathed in the air from his room. He imagined it felt freer inside his lungs than it had felt. But this feeling alone was not the confirmation he needed after so many years and disappointments, in order to dare to allow his emotions to feel free and his soul to feel ecstatic gratitude. That must come in some other way. But what would the sign be that even tiny Borsa-Dej was now liberated? The snow had become more than a crystalline mist. Fat silvery flakes were bouncing on the beams of light that stabbed the darkness outside his window. Now that the day was over, as evening came, it was time to celebrate Christmas. And, even though the thrilling thoughts of freedom from fear and peace on earth would not go away, it was time to open the church doors to receive the villagers’ annual pilgrimage. Inside the chapel the candles were ready for lighting and the nativity scene was arrayed in front of the communion table. There, solid Joseph, radiant Mary, and the Christ-child lying in a manger with chubby arms reaching toward heaven were in place as they had been every Christmas since a woodcarver had brought them down from his Carpathian cabin high up on Mount Pietrosu one Christmas Eve a hundred and thirty years ago. That loving generosity had initiated a Christmas tradition in the Reformed Church of Borsa-Dej. From then on, people had brought an offering for the Christ-child every Christmas Eve, some carved trinket, or a sack of grain, or a jar of preserves. It was a love offering that Pastor Laszlo shared with those of the parish who needed an extra measure of love. Reassured that everything was in place and ready, Laszlo reached for a rope hanging from a hole in the ceiling of the vestibule and began to heave on it. Gently, the stentorian toll of the great bell in the tower began to remind the faithful that the Christ-child was waiting for them. After several minutes of ringing, more than usual perhaps, because of the excitement in his heart that threatened to break out at any moment, Pastor Laszlo went back to collect his thoughts and to pull on his antique black robe with its high frilled white collar of the Reformed faith. Nicola Botez had climbed the tiny stairs into her nest above the back doorway where the organ was hung, and she was filling the room with sounds of Christmas. There was no doubt of the signs of Christmas, Laszlo reflected. But what would be the signs of “Peace on earth?” Laszlo half expected angels to announce the advent of this peace with its new liberty, or perhaps the dazzling glory of a star from the East penetrating into the chapel itself. He was prepared, it seems, for any scene but the one that presented itself to him. As Pastor Laszlo stepped into the pulpit of the church of Borsa-Dej, Comrade Nicu was not standing in his customary place. For twenty-three years, Comrade Nicu had stood in the back of the church every Christmas eve transcribing the pastor’s comments and recording the names of every worshipper. At Laszlo’s appearance, Nicola pounced into the familiar beginning of “O Come All Ye Faithful,” so that the faithful of Borsa-Dej could process to the manger with their Christmas love offerings. In the midst of all the commotion, the door at the back of the chapel opened unnoticed by everyone except Pastor Laszlo who was ensconced in the elevated pulpit. Onto the end of the procession came three people whom Laszlo did not recognize until he got a better look at them, Nicu Hoge with Corneliu and Elena Ratescu. By now the whole assembly was watching them as they found their way to the holy family. There from the folds of his long green coat Comrade Nicu extracted a ponderous sheaf of twenty-three reports on yellow paper from his twenty-three years of vigilance. These reports would never find their way into any investigations nor into any police file, for at the manger he filed them with Jesus. Then, for the first time in his twenty-three years, Nicu Hoge bent down to kiss the forehead of the infant in the manger. Laszlo admitted at last that the static-distorted message he had heard from the radio and the much clearer message from his tattered book of Luke were both true. Corneliu and Elena were back home in Borsa-Dej in the mountains they loved. The war against the innocents must be over as well. Even men like Nicu Hoge were free to love Jesus, and after years of secrecy, to show their love. There was no need for another sign. Pastor Laszlo had seen the sign in Borsa-Dej that God has pronounced, “Peace on earth.” Postscript: This story was written for the Christmas Eve service of the First Presbyterian Church of Alton, Illinois, before the amazement diminished that the Soviet Union had ended and the Cold War was over. Of all the final acts by the dictators, the atrocity during the days before Christmas inflicted on hostage children in Bucharest by the Ceausescus was the bloodiest. On Christmas Day the tyrants were shot by a firing squad. After 30 years it is growing hard to remember how astounding and difficult it was to believe the nightmare was probably over. Our forgetfulness comes with a risk. Again we seem to be forgetting what life was like when dictators ruled. [The picture above is of the Calvinist Church in Dej. The story imagines Borsa-Dej as a smaller village than any of the real towns of Borsa or Dej. The characters are imaginary, but the setting is as authentic as I could compose from news on the three days before Christmas 1989.] A couple of weeks ago my Facebook posts were loaded with a shocking set of pictures. I have posted one of them so you can get the idea. Clearly, SANTA’S REINDEER ARE LOST! They were photographed wandering around in downtown Alton, Illinois. I was a resident of Alton 25 years ago and I can testify that in nearly a decade, winter or summer, we never saw a single reindeer or any other kind of deer wandering around in front of the library in the business district. So, even though the deer population in Illinois has reportedly risen dramatically, there can be no doubt at all these reindeer are lost!

It isn’t fog that did it to them, as in the 1939 tale told by a Montgomery and Ward ad-man, so that Santa called upon sad Rudolph to lead his sleigh that night. The song based on the little story has become so well known, and cartoon versions so universal, that it is no longer acceptable to talk of just 8 reindeer, named by Clement Moore in his poem published first on December 23, 1823. There now have to be 9, led by the most famous reindeer of all even if the night is clear as it was in “O Little Town of Bethlehem” as Phillips Brooks remembered it from his visit on Christmas Eve in 1865. He said that the night was the same as the night Christ was born. The sky was filled with silent stars and then broke “the everlasting Light,” seen first as a star guiding Magi from afar with their gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Santa brings the gifts now, with a lot of assistance, but it’s still up to him and his reindeer WHO ARE WANDERING AROUND, LOST! But I have a concrete solution. We all know that things have expanded since 1823 when Moore described the reindeer as “tiny” and Santa as “a little old driver” and “a right jolly old elf.” Thomas Nast, the most famous cartoonist of the 19th century, depicted Santa Claus as an elfish fellow, but that would never do. Someone is needed between miniature and gigantic, as is the star in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. That immense balloon-size Santa would never fit onto a throne in a shopping mall, much less get down a chimney. In fact, by the middle of the 20th century the chimney thing was glossed over, except for stockings hung carefully close by if there is a fireplace. No, Santa has grown. Santa needs to be human-size in order to help sell things. The classical pictures were in advertisements by Coca Cola. There is no doubt what scale Santa was, because everyone knows what size a bottle of Coke is. So there you are. It’s time to get over the notion that bulky Santa could be gotten aboard a tiny sleigh. The sleigh would have to be both big and able to navigate in climates without snow. If the climate keeps getting warmer as it is now, there might not be snow on rooftops pretty soon. I think Santa has abandoned rooftop landings as he has his slimming diet. Just this week I saw the group of sleigh or wagon pullers a Santa needs around here. No worries, mate, reindeer lost? Here’s your substitutes…. WHO ARE INDIGENOUS PEOPLE AND WHAT DO THEY WANT?

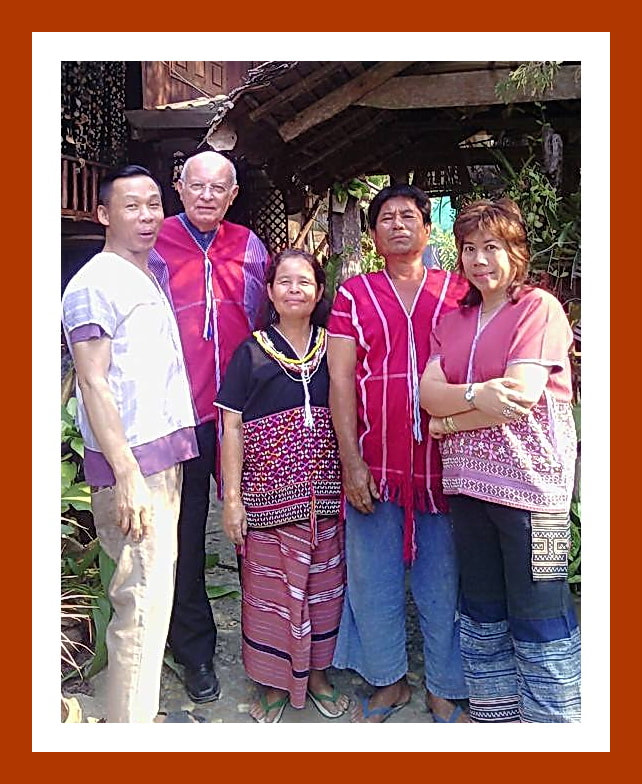

Never, since 1492, has the question been so hotly debated, “Who are indigenous people and what difference does it make?” The Persians and the Greeks accommodated indigenous people in ways that would bewilder Europeans voting for Brexit, North Europeans scared of an influx of Syrians and Turks, and white Americans building a wall because they don’t live on an island. Thanksgiving in the USA, the coming election, and the challenging season of Advent and Christmas turn spotlights on indigenous and migratory human movements and challenge the sentiment that one ethnicity must be dominant at least within a particular boundary. The harsher name for ethnicity is tribalism. It is this that has become the actual rationale for pretty much all geo-political action since … well … a long time. Just since World War Two, which could have ended international imperialism, and since the end of the Soviet Empire 30 years ago, ethnic cleansing and re-emergent tribalism have murdered millions and brought the world to the brink of insanity and (arguably) extinction. Back to the more limited topic of who are indigenous people and what they want. How can you tell? Who, for instance, is “indigenous” in the picture that accompanies this essay? This week Cliff Sloane provided an article written by Ian G. Baird, entitled “Indigenous Peoples of Thailand: A contradictory interpretation” published in Asia Dialogue, a journal of the University of Nottingham Asia Research Institute. Baird’s contradictory interpretation is that movements for indigenous rights and restitution are limited to areas where settler colonizers moved in overwhelming numbers and blotted out the indigenous culture and often most of the indigenous people. He laments that the Thai government avoids efforts to focus on indigenous sub-cultures while in other places (such as the USA and Australia) survivors and descendents have begun to try to reclaim some of what their ancestors lost. But in places where the in-migration was not across “salt water” the idea of some people being indigenous and not others has not taken hold. [Baird’s article is worth study if you are interested in Thailand’s ethnic issues, but it is also relevant to what is also going on world-wide.] I have no intention of disputing Baird. I think he is right. I just want to mention that there are additional reasons why the idea of indigenization (and race, for that matter) evades the every-day consciousness of people around here and different ways of measuring progress aside from what the government is doing on paper. (1) HM King Bumiphol, Rama IX (whose birthday December 5 is a national holiday and “Father’s Day”) and his mother made a very large impact on gaining status of many kinds for ethnic minorities in Thailand. They spent decades expanding commercial options and government services to marginalized people. Without them the country would still be ignoring ethnic diversity in favor of centralized cultural dominance and the accompanying opportunities for government entities to exploit these people. The work, however, is unfinished although the momentum toward fuller acceptance continues. (2) Cultural centralization is increased by the general preference of oncoming generations of people from ethnic backgrounds to enter the financial mainstream and gain its advantages of security and comfort. They may still wear ethnic items of clothing, but ethnic culture is selective and optional for them if they can pull it off. The drive is to get language, education, and vocations to join the mainstream. The idea of ancestral lands and customs being buried and stolen is hardly remarked on. In fact, regardless of historical reality, most ethnic minorities passively accept the idea that their lands really belong to a higher entity and they have moved uninvited onto it from where they actually belong. The motive for this forgetfulness is that they feel identified with people whose demographic center and cultural base is elsewhere. “Our people are over there.” Historical reality is that they have lived where they are for several generations and when they moved there the area was dominated by an entirely different military power than the one that claims sovereignty at present. (3) When it comes to drafting legislation and national policy, political action to accommodate ethnic sub-cultures and minority religions inevitably bogs down when it becomes apparent that whatever is done must also apply to those in the southernmost provinces. The Muslim population in the 3 provinces bordering Malaysia has never been reconciled to the military and political take-over of their Pattani Sultanate by the Bangkok government 150 years ago. The least that must be done is to acknowledge their religious rights. This sometimes works to the advantage of minorities, holding the zealous majority at bay from such things as declaring Buddhism the only national religion, but often simply results in the parliamentary political conclusion, "We're not going to touch that, yet." So the government signed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples without being able to specify what to do about those rights. (4) Baird makes an excellent argument for seeing the drive for making ethnic cultural rights official as being restricted mostly to places where settler colonialism took place, whereas elsewhere it has been common to disregard cultural minorities because "they are just varieties of us, after all, deep down." "Just more of us" breaks down, of course, when things like full citizenship or property rights are opposed for "some of us" who are really "actually them." Meanwhile, some of the old ways are being neglected, and cultural knowledge is slipping. Nostalgia is a motive to hang onto some of it, and commercial possibilities tend to help. When ethnic textiles or household utensils become marketable, it’s considered a “win” and hardly anybody objects that the products have to be repurposed to sell. At the base, where it matters most that an ethnic culture is valued and fought for is whether the language, activities of daily life, and opportunities for children growing up are thought to be better inside the ethnic culture or not. (5) If the dominant culture begins to lose its allure, especially if there is rot perceived in its elite, previously subjected sub-cultures may re-emerge. As time goes on, for example, Lanna history and mores are being reasserted and the prevailing narrative of the North being rescued by Bangkok is being disputed more openly. This ability to tell a different story about how Lanna was conquered rather than liberated, in the face of fierce opposition by the story-spinners in Bangkok, is ironically enabled in part by the momentum that continues to sustain and empower other ethnic cultures whose people are even more easily identifiable as immigrants. As Karen (Paw-ka-yaw) and Hmong communities gain civil rights and yet sustain pride in their ethnicity, the idea of being proud of diversity takes root. National unity does not HAVE to mean cultural subjection. Finally, this is a timely seasonal reflection. For Christians, Advent leading to Christmas is a reminder of the intention to create a different kind of realm. Kingdom was a term of the era in which Jesus was advocating the things that now come under the heading of human rights and human unity. Political powers, kings and Caesar, were not going to do the job of valuing human life differently. Only a divinely inspired grassroots respect for diversity and inclusion have the potential needed. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed