|

These two Halloween stories are how I remember them after all these years. In other words, accuracy is coincidental. The most haunted house in Chiang Mai is gone. I noticed a big plowed field the other day where the house had been since I arrived in the city 53 years ago. As it happens, Google Maps’ street view still has a picture of the old colonial house. It has been vacant and for sale since I first laid eyes on it pedaling my bicycle from language school. It is one of several built when wealthy foreigners and patrons came to town. There was a disaster that few spoke of, that decimated the original family. After a while new owners took over, although they had trouble recruiting domestic staff because the place was famously haunted. Accidents, a fire, disease and then two more suspicious deaths and a horrible hanging added to the ghosts. No one has dared to move in since. Twice the property changed hands and went on sale. It is in a prime location and was of sturdy classic stucco on 3 layers of bricks. It was the sort of place that had historical value, except it was deadly. It was too haunted to inhabit. We’ll see what is planned for the vacant lot. Probably the most expensive piece of derelict haunted property in Chiang Mai is the former Poi Luang Hotel. It still stands, gutted and forlorn, as well as perpetually for sale. The hotel was constructed during the first wave of the tourist boom. It sits on the corner of the highway to Bangkok and Sankampaeng Road which was being developed to attract tourists and showcase Chiang Mai’s amazing handicraft industry – silk weaving, wood carving, traditional umbrellas, silver craft, celadon pottery, bronze ware, gems, lacquer ware, basketry, teak furniture, and much more. The hotel had a revolving restaurant on top that revolved about twice and couldn’t be coaxed to do it again. Sometime in the late 1980s there was a tragedy, resulting in deaths (or maybe I’m confusing that with the Chiang Inn where Legionnaires’ Disease killed a bunch), anyhow, guests began reporting ghosts in the hallways and registrations fell way down. No amount of exorcism could get rid of the ghosts. The hotel was sold to a consortium of physicians who began to convert it into a hospital. As the hospital-to-be was encased in bamboo scaffolding a storm tore some of it down taking a couple of construction workers to their deaths. It was one thing after another. Then the 1997 Asian financial crisis bankrupted the consortium. The building has been vacant ever since. The hotel was briefly attractive for clandestine trysts. The last one of those ended in a murder, adding still another ghost. Graffiti enthusiasts gave up shortly afterward, telling tales of ghosts they encountered. I understand the estimated cost of tearing the building down is still more than the property is worth. So the ghostly hotel remains, haunted. This Halloween blog marks the end of our sixth year. This is our 312th posting, for an average of exactly one per week. At present we have about 2500 “hits” a week by 400 of you. Next week we will begin year seven on the same eclectic range of current events, LGBT issues, Northern Thai village life, and Thai Buddhism and Christianity. Again, thanks to our intrepid webmaster for his skill and persistence. Blessings to everyone as we maneuver through trying times.

4 Comments

Nominating Sirisak Chaited as THAI TRANS HERO OF 2018.

Evidence that Sitisak (nickname Ton) is our most forthright advocate of gay rights is Ton’s own postings on social networks. [Pictures above and permission to use them and say nice things about our hero were obtained in an interview October 23, 2018]. Sirisak has smashed barriers and defied boundary markers more boldly than anyone in Thailand this year. He has rebranded himself as the bald binary bomber. Sirisak’s identity is fluid. “Now she’s femme … now he’s not!” Always both. Sirisak is so “Teflon” nothing sticks. Lately, Ton has been attracting attention wearing nothing but a couple of conflicting gender signals and holding a sign or two warning against a range of conceptual wrongs. Nobody attracts attention like Sirisak. Sirisak Chaited is a Chiang Mai resident. He graduated 15 years ago as a German language major from Payap University. He has been a gender rights advocate for nearly two decades and has been an activist volunteer since 2545 (CE 2002). He spends much time with M+, Chiang Mai’s best known HIV-AIDS prevention and education organization. He is owner of two businesses in Chiang Mai, from which he still manages to take time to respond to invitations all over the country to represent gender-rights causes. Meanwhile, on the other side of the globe we hear a memo of the Trump administration has been leaked to the New York Times in which the US government is proposing to re-define transgender out of existence. The idea is to make it definite under the law that one’s sexuality is exclusively and unchangeable the one assigned at birth. That would make “Transgender” as well as “Intersex” legally impossible, and pave the way for still more oppressive actions against the rest of us on the LGBT spectrum. Backlash and furor have been immediate. I have doubts about this flash. Every time some outrage has been ignited by Trump-Pence in the past two years, it’s served to deflect attention from something wretched being concocted by Ryan-McConnell-Pence a few blocks away. At the moment, it occurs to me they’re afraid the election in 3 weeks may be trouble for them. What better way to get their homo-hysterical voter base agitated than to have them inflamed with pictures of angry people massing in front of the White House with pink and powder-blue flags? We are so manipulated. It is a delicate time in both Thailand the USA (not to mention Taiwan, Malaysia, Russia, and scores of other countries). Basic human rights incorporated in national laws are being acted upon. In Taiwan, a national referendum about marriage equality is coming on November 24. In the USA a national election on November 6 may help restore power to balance decisions on gender issues upset by recent Supreme Court appointments. In Thailand, committees are gathering opinions about how to expand civil rights to persons, regardless of gender. It will make a big difference if individuals get to designate their sexuality in the forthcoming Thai constitution expected before national elections next February. Here in Thailand political activism is suppressed, but for the time being the door is again open for human rights advocates to raise consciousness on issues and help generate positive public opinion. Sirisak has turned himself into an icon, and now that he is a celebrity he is even being invited to lead training sessions for novice advocates. Internet social networks provide a forum, to which Sirisak’s protégés, followers, and target audience devote hours a day; but he has the courage to be fabulous enough to grab their attention. He is recognized, but he is brilliant at turning his recognition into advocacy for every form of gender diversity. I wish we had more heroes like Sirisak Chaited. There has been a lot of talk during the last couple of weeks about how dangerous it is for boys (and men) these days, because if they are accused of being predatory they are guilty until proven innocent, which is next to impossible. Although I agree with the #Me Too movement, I am reminded that this issue is certainly not new. Peter Pan comes to mind.

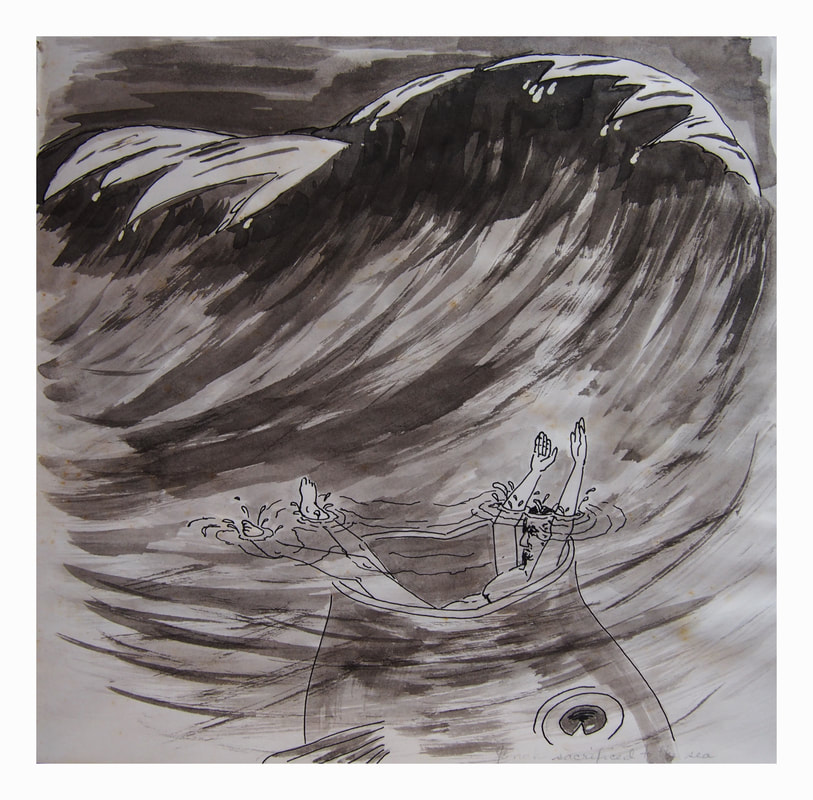

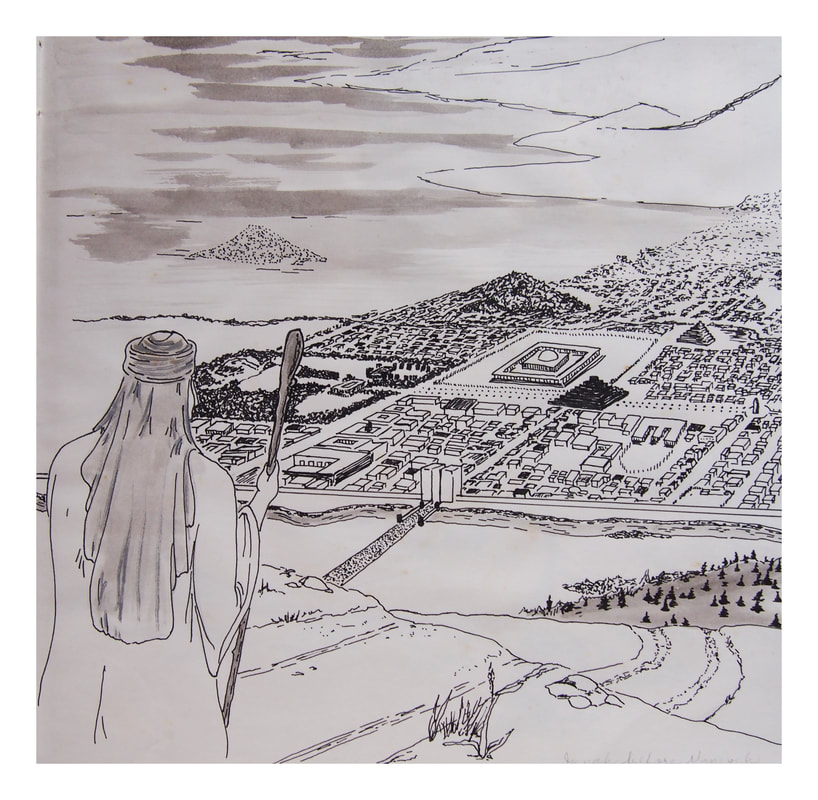

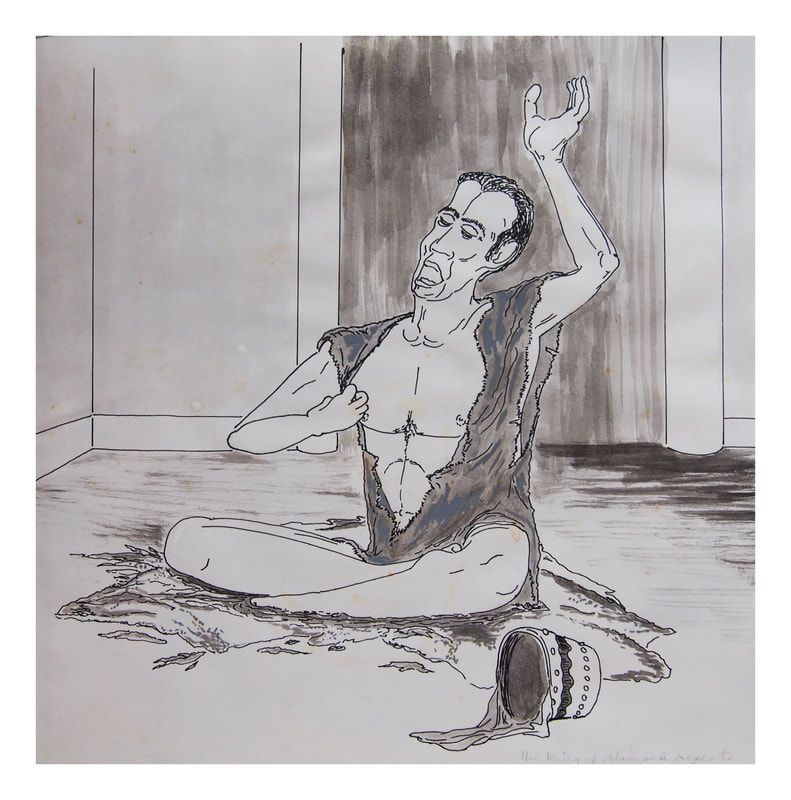

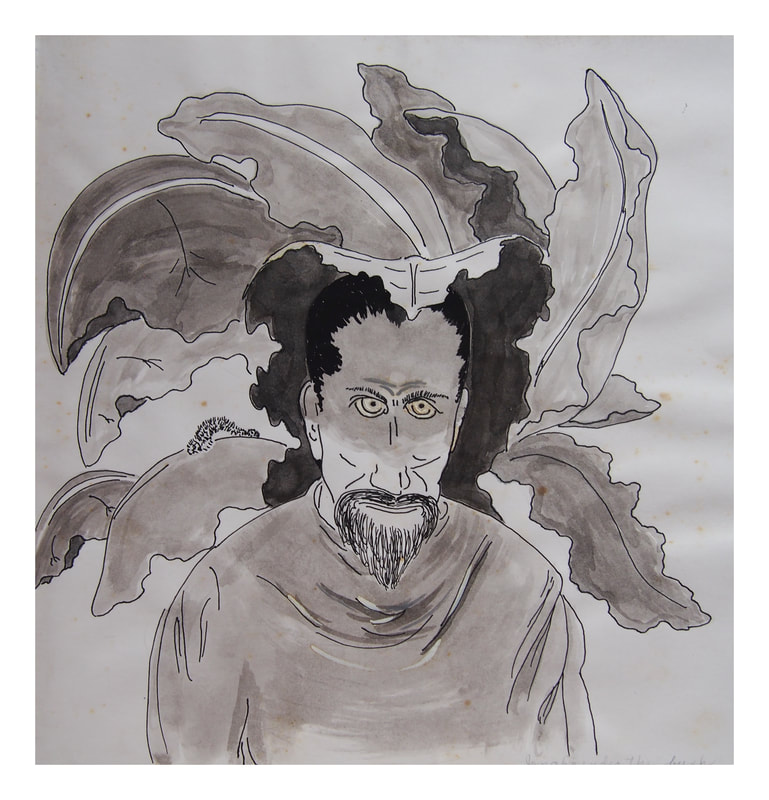

Peter Pan was domesticated the night of December 27, 1904 when the curtain opened at the Duke of York’s Theater, London on the first night of “Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up.” The character of Captain Hook on stage was so commanding that when Peter was victorious he was a hero. This is not what J.M. Barrie had in mind when he wrote the play. To Barrie, Peter was a shadowy character, reflecting Barrie’s own ambiguous relationships with adults and peers. Peter had a vivid fantasy life which blocked his ability to come back home from one of his flights of fancy (that and his mother’s fickle affections which she transferred to a new sibling). From then on Peter was locked out of his home and stranded in Neverland where he was chief of a gang of boys whom he had enraptured, captured, bullied, sometimes killed, and constantly controlled through mind-games. Neverland, as Barrie conceived it, was no idyllic playground, but was a prison island where the inmates battled for their survival simply because war-games were what they knew. Barrie’s conception was that the boys handled their survival struggles by treating them as childhood play, rather than face the grim reality that it was actually about life and death, as all life is. In Neverland it is the trickster, the conjurer of fantasy, who is in control and who is fulfilled by consigning his prey to perpetual childhood. That, and only that, is the central fact about Neverland, although a century of gossip mongers have persisted in projecting their comparatively pale, pedophiliac phobias onto the lords of Neverland, the asylum for boys who wouldn’t grow up. It might be a stretch for us, after decades of indoctrination and consciousness-raising about the latent debilitating effects of sexual child abuse, to agree that there are worse things than can happen to a boy. The court of public opinion has been swayed by testimony from his boys who wouldn’t grow up and his biographers, that Barrie was probably sexually impotent, that he never made sexual advances, and that his guilt was different than suspected. It now seems clear that James Matthew Barrie “did a ‘Peter Pan’” and engineered a complex scheme to abscond with a couple’s boys, capturing them for himself, and in the process gestated the story of “Peter Pan and Wendy”, as he entitled his book finally written in 1911. The boys in question were the five sons of Arthur and Sylvia Llewellyn Davies. In 1897 Barrie loved to walk through Kensington Gardens, where nursemaids aired their charges in prams and children cavorted. Barrie loved to play with them, games of imaginary pirates and Indians which he acted out energetically and embellished with magic tricks, accompanied by his shaggy St. Bernard. That is how he became acquainted with the Llewellyn Davies family, at length managing an invitation to a social event with them. Over time Barrie became a close friend and then a virtual relative affectionately called “Uncle Jim”. When the boy’s parents died of cancer Barrie adopted them with the concurrence of the other relatives and on the strength of a handwritten letter in which Sylvia appeared, as Barrie had altered the document, to transfer her sons to Barrie rather than to her sister. Barrie was close to the clan; it was Sylvia’s own brother, Gerald duMaurier, who played Captain Hook and Mr. Darling in the performance that launched Peter Pan into mythic status and made J.M. Barrie rich and famous. What was sinister about that was that Barrie’s love of the boys was possibly predatory. If Piers Dudgeon is right, as his exhaustive study concludes, Barrie had been scripted by the death of his brother, David, his mother’s favorite. Only when David died of a skating accident was the way open for little Jimmy into his mother’s arms. Anthony Lane says this taught Barrie that “…a perfect child who dies on the eve of his fourteenth birthday will be spared the degradation of growing up, and…the boy will seem scarcely to have passed away at all.” So Sir J.M. Barrie came to power. He had sons he wanted and he was a widely acclaimed playwright on his way to wealth and glory as a baronet and OM. Dudgeon is convinced and convincing that Barrie filled his own sexual vacuum with these little boys he had stolen from their family. Tony Rennell refines that estimation, “…his thrills came from the power dynamics of relationships and playing mind games with people, at which he proved a master. That was what made Barrie a dangerous man to know, particularly for children.” The strongest evidence that this was pernicious is culled from surviving letters and corroborated by the tragic deaths of the Llewellyn Davies lost boys, one of whom died in World War I, a second in a drowning (double suicide?) wrapped in the arms of his boyfriend, and a third finally succumbing to the relentless pressures of life identified as a “lost boy in Neverland” by committing suicide, throwing himself under the wheels of a subway train when he was 60. Dudgeon configured that as evidence that the Llewelly Davies boys were undermined by Barrie’s own emotional issues by which they were entombed in eternal, inescapable childhood where Barrie needed them to be. J.M. Barrie is doing better as time goes by. A 2004 bio-pic about Barrie, starring Johnnie Depp, is kind. And now, serious scholars are daring to depart from the curious idea that Barrie caused the suffering and deaths of the Llewelly Davies boys he loved by life-casting them as little lost boys who can never grow up. It is not politically correct and it is professionally dangerous to come to the defense of an accused pedophile these days. “They should just be ‘put down’ like a mad dog,” one Internet posting suggested. But Justine Picardie re-examined the evidence about Barrie and concluded, “I remain…uncertain about J.M. Barrie who seemed not to be out to corrupt boys with adult desire, but for himself to rejoin them, in the innocence of eternal boyhood, in a Neverland where children fly away from their mothers and no one need grow old.” References: Picardie, J. “How Bad Was J.M. Barrie?” The Telegraph 13 July 2008 Lane, A. “Lost Boys” New Yorker Nov. 22, 2004 Rennel, T. a book review of P. Dudgeon, CAPTIVATED: J.M. Barrie, the duMauriers and the Dark Side of Neverland. Chatto & Windus, 2008 Once upon a time there was a prophet named Jonah. God said to him, “Do your duty. Go to Nineveh and prophesy.” But Jonah hated those people, so he got on a boat going the opposite direction as far as it would go. Not so long ago a preacher was told, “Go to the Capitol and tell them what Jesus said.” But the preacher thought those old boys were doing great. So he went on TV to tell the world how God loved what was going on. Out in the middle of the sea a great storm blew up. It grew stronger and stronger, threatening to tear the boat apart. The ungodly sailors, however, caught on that this storm was telling them something. Tumult began to ravage the land, as historic hurricanes beat upon its cities, and illness went untreated because of huge costs. People everywhere began to worry something had to be done quickly. Jonah confessed, “Throw me into the sea and you’ll be spared.” The godless sailors hesitated to be so cruel just to save themselves but finally they yielded. The last they saw of the prophet, he was being swallowed by a huge fish. In the back of the preacher’s mind was concern that those old boys in Distant Capitol were trashing all the values the preacher and his crowd had stood for, but they hated the same things and feared all those people of different colors. The preacher said, “What’s a little wind and rain when we’ve got such fine old men making things great again.” But some were watching in amazement, “OMG! The preacher’s been swallowed whole!” Down in the deadly deeps, Jonah was wrapped in seaweeds as he succumbed to despair that led to confession. Even in the deadly deeps God was paying attention to Jonah, and God ordered the fish to puke the prophet out back onto the beach where he had started. The preacher grappled desperately trying to figure out how to be both true to Jesus and loyal to the good old boys thumping each other on the back as they piled up their profitable deals. At last the preacher found himself right back where he’d started Jonah made it to the huge city of Nineveh, home of the horrible people Jonah hated most. He vowed to do the absolute minimum. Getting himself barely inside the vast city he announced, “You’re done for, three days from now.” Then he turned around and left. “Well, these days of high-tech, one doesn’t have to really GO to Distant Capitol to have one’s voice heard there,” the preacher decided. So he went on TV again, waved his hands comfortingly and crooned, “Remember Jesus.” Well, that wasn’t so hard Word spread throughout Nineveh. Panic resulted. The king himself tore his royal robes, put on a burlap shirt and wailed repentance sitting in ashes. The whole city fasted and prayed. Nineveh turned to God. God spared them. The tousle-headed Good Old Guy was congratulated by his wattle-chinned prime mover. PM declared, “It’s a wrap. We got’em now.” The city was in their hands court, capitol, commerce, and all. Jonah was livid. “I knew you’d do that!” he railed at God. Poor Jonah wanted to see Nineveh in flames, but all that happened was his own shelter was eaten by worms so it was he who suffered from the heat. He heard that dreaded voice again, “Jonah, Jonah! You’re pissed off at me for saving these millions? Get a grip. Think!”

Outside the city, millions were no longer listening to the preacher. They hadn’t heard him say a word from Jesus for so long that they no longer expected to hear any. They had heard from Jesus directly, however, and they were on the move. Integrity is the integration of a person’s parts into a contiguous whole, particularly the intellectual and ethical aspects. Integrity means that beliefs and actions, values and expressions, are consistent. One comes to a sense of self-identity by the development of this capacity.

Jean-Paul Sartre was a spokesperson for this way of thinking, and the most fascinating expressions of his rigorous and courageous point of view were in his stories, novels and plays, for which he became world famous, a Nobel Prize recipient for literature, and that rarest of phenomena for philosophers, a popular celebrity. In story after story, Sartre describes how, among our range of options, we choose that which we value most to express who we are. In his story “The Wall” three prisoners are sentenced to death. They are held in a coal cellar to await their execution the next morning. As the night wears on the prisoners begin to lose their sense of being normal human beings and begin to die. In the state I was in, if someone had come and told me I could go home quietly, that they would leave me my life whole, it would have left me cold: several hours or several years of waiting is all the same when you have lost the illusion of being eternal. I clung to nothing, in a way I was calm. But it was a horrible calm – because of my body; my body, I saw with its eyes, I heard with its ears, but it was no longer me; it sweated and trembled by itself and I didn’t recognize it any more. I had to touch it and look at it to find out what was happening, as if it were the body of someone else. At times I could still feel it, I felt sinkings, and fallings, as when you’re in a plane taking a nosedive, or I felt my heart beating. But that didn’t reassure me. Everything that came from my body was all cockeyed. Most of the time it was quiet and I felt no more than a sort of weight, a filthy presence against me; I had the impression of being tied to an enormous vermin. Once I felt my pants and I felt they were damp; didn’t know whether it was sweat or urine, but I went to piss on the coal pile as a precaution. [Sartre, p. 182] What Sartre is describing, with eloquent pathos, is a sense of disintegration, of fragmentation, and of losing touch with physicality (as well as transcendence, of which Sartre is unremittingly contemptuous). Finally, the narrator, Ibbieta is isolated, with 15 minutes to live. He can tell his captors where the revolutionary leader Ramon Gris is hiding or Ibbieta will be shot. It is the critical moment of the story. I…knew that I would not reveal his hiding place. …All that was perfectly regulated, definite and in no way interested me. Only I would have liked to understand the reasons for my conduct. I would rather die than give up Gris. Why? I didn’t like Ramon Gris any more. My friendship for him had died a little while before dawn at the same time as my love for Concha, at the same time as my desire to live. Undoubtedly I thought highly of him: he was tough. But it was not for this reason that I consented to die in his place, his life had no more value than mine; no life had value. They were going to slap a man up against a wall and shoot at him till he died, whether it was I or Gris or somebody else made no difference. I knew he was more useful than I to the cause of Spain but I thought to hell with Spain and anarchy; nothing was important. Yet I was there, I could save my skin and give up Gris and I refused to do it. I found that somehow comic; it was obstinacy. I thought, “I must be stubborn!” And a droll sort of gaiety spread over me. [Sartre, p. 185] “I would have liked to understand the reasons for my conduct,” Ibbieta says, and finally concludes, “I must be stubborn!” It boiled down to that, nothing more noble or patriotic for Ibbieta than simple stubbornness. However, for Sartre, there is a great more about it that can be said. All of philosophical existentialism, in fact, is behind Ibbieta’s stand and, Sartre contends, our stands as well. In his essay “Choice in a World Without God” Sartre says: “If, however, it is true that existence is prior to essence, man is responsible for what he is. Thus, the first effect of existentialism is that it puts man in possession of himself as he is, and places the entire responsibility for his existence squarely on his own shoulders. And when we say that man is responsible for himself, we do not mean that he is responsible only for his own individuality, but that he is responsible for all men.” [Sartre, p. 187] Sartre was certainly aware that the philosophic background for this position is Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Kant’s famous Categorical Imperative that we should “act only according to maxims which you can will also to be universal laws.” In itself, the categorical imperative is not a revolutionary concept, being found virtually everywhere from the so-called Golden Rule attributed to Jesus to Confucian dictums. It was existentialism’s contribution, to insist on this as its “first effect” and to attribute to this ethical principle the role of defining one’s entire destiny. Of all the actions that a man may take in order to create himself as he wills to be, there is not one which is not creative, at the same time, of an image of man such as he believes he ought to be. To choose between this or that is at the same time to affirm the value of that which is chosen; for we are unable ever to choose the worse. What we choose is always the better; and nothing can be better for us unless it is better for all. [pp. 187-8] Put in more facile terms, “In a Godless world we have no alternative but to choose, and in that sense create, our own values. Yet in doing so we are laying down the ground rules of our own lives. And in doing that we are determining how our own personalities develop: we are creating ourselves.” [Magee, p. 217] It is a frightening responsibility to be the creator of one’s self. Some forms of Christianity would relieve us of that by having us be compliant to the benevolent plans of a loving God. Sartre recommends that we always choose that which is better, but he does not say that the better is always, in all circumstances, the ideal. Existentialism is far from idealism. Sometimes the operational principles a person uses are mundane, as when Ibbieta decides to do what he does for no lofty reasons, but because he is stubborn. In another script Sartre would have Ibbieta agree that stubbornness in such circumstances would be recommended for all of us. If, moreover, existence precedes essence and we will exist at the same time as we fashion our image, that image is valid for all and for the entire epoch in which we find ourselves. Our responsibility is thus much greater than we had supposed, for it concerns mankind as a whole. [p. 188] That, then, is existentialism’s basic social philosophy. Existentialism’s individualism avoids social chaos by a deft delegation of responsibility, which is based on the premise that human beings are rational. When a man commits himself to anything, fully realizing that he is not only choosing what he will be, but is thereby at the same time a legislator deciding for the whole of mankind – in such a moment a man cannot escape from the sense of complete and profound responsibility. [p. 188] Of course, Sartre, of all people, was aware that much of modern history, and contemporary European history, 18th and 19th century French history in particular, bear witness to an irrational, chaotic bent to human social behavior. What of those who are not apparently upset by the greed, sadism, depravity and conceit that their characters and their behaviors exhibit? There are many, indeed, who show no such anxiety. But we affirm that they are merely disguising their anguish or are in flight from it. Certainly many people think that in what they are doing they commit no one but themselves to anything: and if you ask them, “What would happen if everyone did so?” they shrug their shoulders and reply, “Everyone does not do so.” [p. 188] Sartre’s argument is not that all people do act responsibly but that they ought to. But in truth, one ought always to ask oneself what would happen if everyone did as one is doing; nor can one escape from that disturbing thought except by a kind of self-deception. The man who lies in self-excuse, by saying “Everyone will not do it” must be ill at ease in conscience, for the act of lying implies the universal value which it denies. By its very disguise his anguish reveals itself. [p. 188] This anguish and regret is a burden that existentialism puts back onto human shoulders and removes from God’s. Existentialism never asks whether God is cruel to allow sinful behavior and natural calamity, or just unable to do anything about it. Kant, refused to deny the existence of God, and insisted instead, “It is thoroughly necessary to be convinced of God’s existence, it is not quite so necessary that one should demonstrate it.” Sartre avoids the temptation to shed the blame for human moral failures by denying that God has any role in human affairs. Faced with rising anarchy that came to its peak in the socialist and communist revolutionary movements, Dostoevsky argued that it is God and divine moral law that form the only dependable barrier to the collapse of civilization. Sartre argues that this felt need for something like God does not mean that God exists. He put it this way: Dostoevsky once wrote, “If God does not exist, everything would be permitted”; and that, for existentialism, is the starting point. Everything is indeed permitted if God does not exist, and man is in consequence forlorn [i.e. in despair and anguish at “abandonment”: Heidegger’s favorite term], for he cannot find anything to depend upon either within or outside himself. [p. 190] As was the ironic hero Ibbieta, Sartre is also stubborn, obstinate in his insistence that human beings are responsible for their actions and the consequences of them. God cannot be blamed. Frightening as this might be, that’s the way it is. Nor, on the other hand, if God does not exist, are we provided with any values or commands that could legitimize our behavior. That is what I mean when I say that man is condemned to be free. [p. 190] “Many people find this freedom and this responsibility too terrifying to face, so they run away from it pretending that they are bound by already existing norms and rules,” one interpreter of Sartre explained. Sartre said these people were acting in “bad faith” and lacked “commitment.” Thus he threw the terms back into the face of the French church. How, without God, does one achieve this type of stability (or stubbornness) and this level of commitment? One of the most ancient prescriptions explains a way: 55 O Partha, when a man relinquishes all the desires of his mind, and when his spirit delights in itself, then is he called a man of steady wisdom. 56 He whose heart is unperturbed in the midst of calamities and free from longing in the midst of pleasures, from whom attachment, fear and rage have departed, is called a sage of steady reason. 57 He who is unattached in all things, who neither exults in nor feels aversion for any good or evil that befalls him, is said to be steady in his wisdom. 58 When a person withdraws his senses from the objects of sense on every side the way a tortoise draws in its limbs, his wisdom is steady. 59 The objects of sense abandon the man who abstains from feeding on them, but the longing for them does not cease. But even this relish ceases when he has experienced the Supreme. 60 O Son of Kunti, these turbulent senses lead away by force the mind of even the wise man who is striving [for control]. 61 Having acquired self-control, he should sit in yoga and meditate on Me [Brahman] alone. He whose senses are thus controlled is steady in his wisdom. 62 A man who contemplates the objects of sense develops an attachment to them; attachment gives rise to desire, and desire results in anger. 63 Anger gives rise to confusion, confusion to loss of memory. Loss of memory destroys intelligence and, once a man’s intelligence is destroyed, he perishes. 64 But the man whose mind is disciplined and whose senses are under control is free from attachment and aversion though he moves among the objects of sense, and such a person attains serenity. 65 And in that serenity, all misery is destroyed; because the intelligence of the man of serenity is also steadied immediately. [Bhagavadgita, ch. 2] Anyone familiar with the Bhagavadgita is aware that the writing is theistic in its orientation and might not fill the bill as a guide for stability free from God. Yet, anyone that familiar with the Bhagavadgita would also know that the advice is shared in common with atheistic and agnostic Hinduism and with Buddhism. It is yoga and meditation that Sri Bhagavan recommends to control attachment and desire, the causes of human suffering. In the Bhagavadgita it is relinquishment of all desires that is the basis of steady wisdom, whereas in the Bible it is fear of (or reverence for) God that is the beginning of wisdom. On the surface the Bhagavadgita has the final word to say about human integrity and responsibility, including the way to achieve it. In actual practice, that may not always be the case. Our friend Linda called yesterday morning from her sister’s house in Virginia. She wanted to hear a friendly voice, she said, “to have a little light in the day.” Linda has come home from the hospital, and is recovering from her second operation on her neck, where they have removed a tumor that was attached to her spinal cord. A month ago she was driving from California to take refuge at her sister’s, after her money ran out, and while she was driving through Texas her left arm went numb and the fingers on her left hand “just went limp.” She got as far as Nashville before she had to pull into a hospital and call friends. “Last time the radiation didn’t work,” she reported. “They say this in incurable. The terrible thing is knowing that in a few months it will be back. It is the pain that gives me the most fear. They give me such heavy doses of medicine to keep down the pain that I live in a blur.” She paused and signed, “I have such morbid thoughts.” Her view of her condition has a right to be morbid, I felt, but I just listened as she changed the subject to her former husband, Ben. He left her and the five girls four years ago to go live with another woman and her 17-year-old heroin addict son. Ben took all the good stuff when he left including the piano and the car, and she had to sue him to keep him from canceling her medical insurance and child support. Now that the girls are grown and the divorce is final, she has nothing. She’s not bitter about being homeless and broke, but bitter that their twenty-year marriage, and even their five daughters, meant nothing more to Ben than they turned out to mean. Then she thought about what she was saying to me, “But you know what I’ve been remembering?” she asked rhetorically. “All those old songs are coming back, ‘Count your blessings, count them one by one,’ ‘Safe in the arms of Jesus,’ ‘I walked in the garden alone,’ songs like that.” Integrity is a product of two fields of energy, so to speak. Concentration, focused attention, or meditation, empowered by energy from the core of our souls in the form of intuition responds to a growing sense of maturity and creativity emanating from our silent center, our unconscious deep within. This maturity comes as freedom from ontological concern, selflessness. Where those two fields of force intersect, there our integrity emerges. Thirty years ago Elizabeth O’Connor penned it this way in a collection of calligraphy: To be a liberating community – the New Community – is to touch not only an individual quiet center, but a corporate quiet center, and to drink as a people out of wells of living water. Out of us will flow an unbelievable creativity. People will begin to marvel at what they see, but that which is happening flows out of an inner life. What is seen is visible as a result of this inwardness – an inwardness that must always be protected, nurtured, and tended. ____________________ Bhagavadgita, The translated by V. Nabar and S. Tumkur, 1997. Hertfordshire, England: Wordsworth Editions Ltd. Magee, B. 1998. The Story of Philosophy. London: Dorling Kindersley Ltd. O’Connor, E. 1976. The New Community. San Francisco: Harper & Row, Publishers. Sartre, J-P. “The Wall” and “Choice in a World Without God” in The World of Short Fiction edited by R. Albrecht, 1969. New York: The Free Press. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed