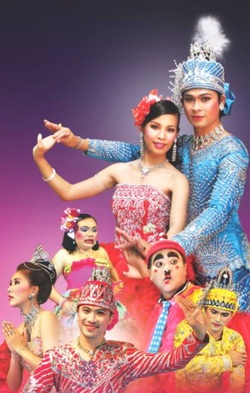

Dare to be ridiculed or you will never be able to get the Gospel into the heart of a culture. Being an inter-cultural Christian is not for the faint-hearted. But daring to make Christian applications of one’s own most venerable cultural treasures is risky, too. The good news of Jesus Christ must be interpreted in order to make sense. First, the Gospel emerged in the Roman colony of Judea and it had to be interpreted for the wider culture which used Greek and Latin as well as a hundred other languages in Gaul, Germania, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Parthia and Persia and even China all within the lifetime of the first generation of Gospel-spreaders. Not only were there language barriers, but the cultures were diverse. The history of the Christian Church can be written as the story of accommodation to and domination (sometimes decimation) of cultures. The parallel history, of course, is about the evolution and preservation of doctrine. The Gospel that goes nowhere withers. In Thailand one of the best known organizations working to interpret the Gospel in Thai cultural terms is the Christian Communications Institute of Payap University. The CCI has been a pioneer in the use of traditional Thai folk melodrama, called likay, to communicate Christian stories and Christian values related to moral and social issues. Likay is a South East Asian folk-art form using stylized costumes and dance movements, traditional music, set characters and melodramatic plot-lines. In this era of information technology when even television is being challenged as the leading medium of mass communication, such highly personal and small scale approaches as likay are disappearing. Where there were hundreds of traveling likay troupes a few decades ago, now there are only a few scrambling for sponsors to bring them to fairs and festivals. But the mere appearance of a poster with likay characters, like the one at the top of this blog, still says “LIKAY” to every Thai person who sees it. A likay character has the power of an icon. But “Christian” likay, is that possible? This was not an easy concept to establish. Cultural traditionalists scoffed that the CCI would erode the art form, ignoring the fact that all art forms are evolving if they are not dead. There was even the call for a royal investigation, which concluded by vindicating Christian likay. Christian traditionalists scolded the CCI for desecrating the Gospel by dressing it up in debauched and pagan attire. But the CCI has prevailed into its fourth decade, performed before audiences in North America, Europe, Asia and Australia, and is now embarking on its 15th international tour that will take a group to churches in California, Texas, Kansas, Iowa, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Kentucky during March. Google: CCI USA Tour or send an e-mail to [email protected] for details. The purpose of performing Christian likay in Thailand is to communicate Gospel messages and show that the Gospel is not a foreigner’s dangerous faith. The purpose of performing Christian likay on international tours is to show that there are many ways to adapt the Christian message without imposing a homogenized “Christian sub-culture” where a vibrant culture already thrives, a concept that early missionaries rejected and current “One Country, One Language, One Culture” advocates seem in danger of forgetting.

0 Comments

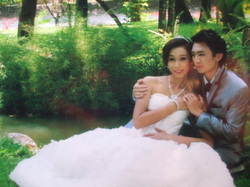

The selfie fad is not as vapid as it appears to be, although it may be as narcissistic. It is an expression of a deep need, and an aspect of postmodernism, which is not a passing fad. Postmodernism has been criticized in the USA in particular, since the beginning of the 21st century, as being obscure, undefined and lacking in identifiable principles. Nevertheless, so-far no better term has become standard to describe the intellectual mindset of these times. Postmodernism is a description of contemporary culture. It is global. It is not limited to selfishness or egocentricity. It is a basic reality which cannot be understood and addressed by minimizing its nature as a character flaw. The selfie fad is a product of postmodernism, and not simply a fruit of modern public-hedonism. Just to be sure we’re on the same page: a “selfie” is a picture one takes of one’s self, usually reflected in a mirror with a hand-held camera or with a more recent i-pad or phone that shows the photographer what the picture will be at the same time the picture is being taken – electronic mirrors that create the illusion of preserving the ephemeral. Postmodernism is more difficult to explain. In order to understand postmodernism let’s take a moment to consider modernism. Modernism was a movement in philosophy and the arts based on identifying basic structures and constructing design universals. Specific aspects or facets of things might be isolated, but they were reflective of mega-stories, universal truths and contiguousness. Before the modernists, romantics like Dostoevsky wrote about war and peace, but modernists like Joyce wrote about even larger entities by detailing the odyssey of one day in the life of an Irishman in Dublin. Postmodernists deconstruct stories and deny the fragments are less significant than an imaginary whole. Postmodernists think that there is much to be gained from ignoring the confinements of structure. An intellectual quest is never most usefully in search of an intellectual thread. There are greater challenges to the imagination. When I was finishing my bachelor’s degree I had the good luck to fill in an elective slot with an art course taught by a young man who also drove formula-one race cars in Europe while he worked for the Doctor of Fine Arts degree in art history. One of the assignments he gave us was to produce a still life of bottles, then reverse the light values so the bottles were in silhouette, then take them apart and rearrange them. I did not know why we were doing that, but I was intrigued by the results. In fact, we were doing with pictures what William Burroughs had pioneered when he cut and shuffled paragraphs to produce his famous Naked Lunch. In the Beat Hotel in Paris, where Burroughs resided for a while, he met Brion Gysins and was inspired by his cutting up pictures and reassembling them in a random manner. It was what Mr. Scott had us doing. Modernists, Picasso, Eliot, Sartre and Frank Lloyd Wright with all seriousness and Salvador Dali with a great deal more mirth, were trying to get to the bottom of reality. Modern art was avant garde. Reality was deeper than superficial appearances. Progress for civilization, in desperate need of progress, depended on starting with what is essential, permanent and below the surface. The hallmark of modernism we might say, borrowing from the art historian E. H. Gombrich, was the “rejection of the study of natural appearances” (p. 622). As the term implies, postmodernism is a rejection of modernism which was a rejection of romanticism with all its Victorian gingerbread, knick-knacks and sentimental ultra-realism. Picasso isolated forms ruthlessly, as did Mondrian, Corbusier, Kandinsky, as well as John Cage with his music and Kafka with his tales. Postmodernism in art is not strictly a return to natural appearances, but to eclecticism. As John Russell Taylor put it in The Times 25 years ago, “…we live in a pluralist world where often the most advanced, being probably post-modern, is likely to look the most traditional and retrograde.” He seems to have been referring to such art as close-ups of flowers, whereas the modernists would have dissected and abstracted the flowers to get to their essence. The 80s was a time in arts and literature when anything goes, including fantasy as truth and reality as fiction. Since then it is pluralism that has flourished in modern culture. Everybody prefaces their essays on postmodernism with the disclaimer that the movement is very hard to describe. But one thing all seem to agree is that it is about language and the use of words or at least signifiers. Philosophically, postmodernism follows logical positivism as developed by Ludwig Wittgenstein in Austria a century ago. Wittgenstein pushed philosophers to admit that there is no reality they can talk about except the words they use. The words never quite assimilate the referents, but just “reach out” to them. This laid the foundation for postmodernism’s denial of realities that cannot be experienced. The postmodern era is positioned to synthesize at…the level of experience, where the being of things and the activity of the finite knower compensate one another and provide the materials whence can be derived knowledge of nature and knowledge of culture in their full symbiosis…. [Deely] This was a disavowal of most of philosophy since Immanuel Kant definitively explained how Descartes could account for the existence of things, rather than insist that their existence must ultimately be accepted on faith, which had been the position throughout the Middle Ages. The philosopher Jean-Francois Lyotard “…argued that in our postmodern condition, … metanarratives no longer work to legitimize truth-claims. He suggested that…people are developing a ‘new language game’ [ala Wittgenstein] – one that does not make claims to absolute truth but rather celebrates a world of ever-changing relationships (among people and between people and the world).” [“Postmodern Philosophy”] Whether in discussions of postmodern philosophy, architecture, religion or art, the rejection of “metanarratives” is key. Postmodern critics of culture argue forcefully that whoever controls the narratives controls the world, and postmodernists do not want that to happen. A metanarrative is a grand story, held in common by an entire population that tells of a great hero taking a great voyage facing great dangers for a great enduring purpose, which inspires and incites the population to coalesce around and support that purpose. On the other hand a metanarrative can also be the narrative of a narrative, as in the case of telling stories about American free-market capitalism as proof of the superiority of the American form of civilization. Another and perhaps better example is the way some feminists assemble a large number of stories to conclude that patriarchy is about the oppression of women. Lyotard’s view was that “local stories” do not contribute to any large truth, and the insistence that they do is an attempt to obtain power over the people who believe in the conspiracy. The emergence of a conspiracy theory is nothing more than a power-grab by those who gather disparate and largely unrelated stories into a mega-story. One of the more cogent interpreters of postmodernism is Dr. Mary Klages, Assoc. Prof., English Department, University of Colorado, Boulder. In an article on literary “Postmodernism” she explains: Postmodernism is the critique of grand narratives, the awareness that such narratives serve to mask the contradictions and instabilities that are inherent in any social organization or practice. In other words, every attempt to create “order” always demands the creation of an equal amount of “disorder,” but a “grand narrative” masks the constructedness of these categories by explaining that “disorder” REALLY IS chaotic and bad, and that “order” REALLY IS rational and good. Postmodernism, in rejecting grand narratives, favors “mini-narratives,” stories that explain local events, rather than large-scale universal or global concepts. Postmodern “mini-narratives” are always situational, provisional, contingent, and temporary, making no claim to universality, truth, reason or stability. Mini-narratives abound. Facebook is rife with them. It is my contention, in fact, that mini-narratives can be the key to understanding modern culture and society. I will not try to account for exceptions, but the rule prevails in all of Europe, North America, urban South America, Australia and New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, and large parts of East Asia as well as wherever the Internet is informing youth about what life is all about. Just to be sure we are clear about the impact of postmodernism and what it challenges (some of which we older residents in this changing world may hold dear), let Klages be heard: In modern societies, knowledge was equated with science and was contrasted to narrative; science was good knowledge and narrative was bad, primitive, irrational. Knowledge, however, was good for its own sake; one gained knowledge, via education, in order to be knowledgeable in general, to become an educated person. This is the ideal of the liberal arts education. In postmodern society, however, knowledge becomes functional – you learn things not to know them, but to use that knowledge. [Klages, ibid] Postmodernism has manifested itself in religion, as well. Postmodern religious systems of thought view realities as plural and subjective and dependent on the individual’s worldview. Postmodern interpretations of religion acknowledge and value a multiplicity of diverse interpretations of truth, being and ways of seeing. There is a rejection of sharp distinctions and global or dominant metanarratives in postmodern religion and this reflects one of the core principles of postmodern philosophy. A postmodern interpretation of religion emphasizes the key point that religious truth is highly individualistic, subjective and resides within the individual [“Postmodern Religion”]. Our thesis is that since postmodernism is the mentality of the modern world, it can be useful to help us understand popular culture. Let’s turn to that now. I am grateful to Stephanie Sklar for her simplified list of characteristics of postmodernism. In my own words and with comments of my own, here is Sklar’s list: Disillusionment with modernist thinking. Modernism did not make strides in achieving peace and progress in society. It was flawed. In other words, peace and progress in society are to be sought by postmodernists. Unlike religious fundamentalism, postmodernism is not simply a negative reaction to modernism. Opposition to traditional authority. Authority is dangerous and untrustworthy. Authority figures are to be opposed. This opposition is valid wherever it happens even though it involves un-peaceful and destructive means in the short term. It is unnecessary to try to account for the apparently inevitable emergence of new authority figures whenever the old authority has been displaced; to try to do so would be tantamount to relying on some universal principle rather than living in the present. Truth is relative. Truth has been defined by people and groups to obtain power. One’s perception of reality may not match another’s perception of the same thing. Truth is subjective. Even such an intimate statement as “he is my husband” is subject to interpretation and shifts of meaning. Facts are useless. Facts can change. Facts may be lies. Facts are contingent upon factors that cannot be assessed; if we only know in part, the part we know is useless. All investigation is inductive but inconclusive. Rationalization. Opinions are what matter, as long as they can be rationalized. Science is rejected since there is no objective reality. Discourse is a game even though the stakes are sometimes high. Beware those who insist that their ideas are more than opinions; they are trying to become your masters. Morality is relative. There is no moral system that is right for everyone. You have the right to just say “no” and you have the right to suggest; infringing those rights is the only wrong. Whenever a religious or social entity stakes its legitimacy on mediating morality it endangers its viability in the postmodern world. Each religion is legitimate. Faith based on personal experiences legitimizes religion for a person. Faith, by definition, involves a decision to embrace uncertainty but then to ignore it; institutional religion, by definition, involves denial of uncertainty. The evolution of every world religion involved the abnegation of the founder’s vision of freedom for believers in favor of the benefits of a mass movement. Belief in internationalism. Nationalism drives nations into conflict with each other. Nations need metanarratives to coalesce adherence; without those grand stories there are no enduring nations. But when a metanarrative about internationalism develops, look behind it to find the puppeteer. Collective ownership. Dividing and distributing goods as a group would be most fair. Left alone, individuals and groups would and always have operated this way; massification of society is the factor that opens the way for manipulation of needs and satisfactions. Given the reality of mass society, however, the collective ownership ideal is diverted and unfairness is rampant. Equality. There isn’t one right way to live. It is a lie that one’s freedom to live according to one’s own vision somehow deprives others of that freedom; every freedom involves responsibilities, but these are realized and not imposed. As I understand it, Sklar has summarized how postmodernism functions in popular culture. This is her sketch about how people operate these days. As a person of an older generation more in tune with James Joyce than Lawrence Ferlinghetti, I am grateful for Sklar’s help in coming to terms with the confusion I feel when I confront the stuff that appears in pop culture and current political battles. As a teacher who believes in knowledge as a benefit, I have trouble with the current trend toward anti-intellectualism and can hardly make sense of it. As a Christian pastor I am convinced of something akin to eternal truth. But then I am a modernist who is frankly in awe of T.S. Eliot and Virginia Wolfe. It is tempting, and perhaps even responsible, to criticize postmodernism, and popular manifestations of it in particular. Mary Klages concludes her lecture with an implied critique, when she calls postmodernism a “movement toward fragmentation, provisionality, performance and instability” and wonders (perhaps euphemistically) if it is good or bad. But if we propose to be responsibly critical of postmodernism we are confronted with two separate tasks: comprehension and critique. We need to conscientiously try to understand what motivates this generation who are now moving to take over the roles we are vacating, before we hasten to lambast it for being flawed and self-destructive. It is easy enough to lay into the contentions that “truth is entirely relative, facts are useless, and opinions are what matter”. It is enticing to rail against how that threatens chaos and anarchy, into which tyranny and totalitarianism are ever ready to move and take over. It is frightening to ponder the results of moral and ethical dissipation. But that sort of critique has gone on for a long time without coming to terms with the essential dynamics that drive popular postmodernism. Postmodernism is what people in this generation are about. Even though they do not put it in so many words, they are individualists at heart. But I do not think that this individualism of the “me generation” completely accounts for the psycho-social dynamics of our times. As Russell Taylor observed, “we live in a pluralist world.” Sometimes this pluralism has turned anti-intellectual as in the phrase “my opinion is just as good as yours.” These are hard times for rigorous studies. All academic endeavors must pass the test of practicality. Things, ideas and people are valid and valuable insofar as they are useful. But useful for what? Not for the great good. There is too much pluralism to assert a general value, or a universal truth. Business and technology, government and education all need people to fill particular functions. There’s nothing postmodern about that, except perhaps the extent that it is true. What is postmodern is that individuals are not dissolved in the process. They do not melt but maintain a natural diversity that refuses to yield to pressures to relinquish completely. They live for something else than the corporation, the nation or any metanarrative. There is a stubbornness about this that screams out for explanation. Why is the selfie generation so fascinated with self-portraiture and “me” micro-culture? Why do people of this time need such constant reassurance? I think the reason for this has to do with the socio-economic megaculture. This used to be called this the military-industrial complex, and we were warned against it before embracing it. What do young adults confront these days? Is it not a maze of barriers that serve more to block than to guide? This is a hi-tech electronic time, following an electric-industrial time, following a steam-mechanical time, and so forth. At the present time knowledge must be digitalized. Otherwise it is meaningless static. The opposite of knowledge these days is not ignorance (something to be defeated by education) but noise. Within this context an individual is a cipher, a digit, a dot. Life in the pursuit of a living involves being submersed, indeed subsumed, in a massive enterprise, the nature and purpose of which are extremely unclear. One can only know a certain part of it; no one knows the whole. It is popular to account for the whole as part of some secret conspiracy, with a hidden manipulator at the controls. The truth, insofar as there is any truth about the phenomenon, is the far more ominous possibility that no one is in control. The parts of some entities that are under control are all parts of larger entities that probably move according to dynamics as inscrutable as the development of celestial galaxies. Even the enterprise in which a young adult finds herself or himself employed is ultimately de-humanizing. The value of workers is measured by their productivity at their task. Were the task to change, as all of them do, a worker trained for the former task becomes extraneous or redundant. This is a constant specter beclouding the horizon toward which every worker moves. It leads to workers feeling tentative and constantly scurrying to avoid inexorable pendulums and dropping trapdoors. Meanwhile, the worker knows that the thing for which he or she is valued (and is being paid) is a minute part of the person’s whole and a fraction of the array of passions and abilities which she or he values. The more trivial the task, the more minimal it is as a measure of one’s life. Livelihood is in tension with life. I will leave it at this for now: “When the context in which people find themselves is exploitative, only the strong survive.” Selfie kids are afraid. They are resisting. And maybe also they are blocking out the wider world by shoving these mirrors and pictures of their food in front of their eyes. Citations: Deely, J. (2001). Four Ages of Understanding, Toronto: University of Toronto, downloaded Feb 8, 2014 from en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postmodern_philosophy Gombrich, E. H. (1995). The Story of Art, 7th Ed. London: Phaidon Press, Ltd. Klages, M. “Postmodernism” http:www.colorado.edu/English/ENGL2012Klagespomo.html downloaded on Feb 8, 2014 from www.bdavetian.com/Postmodernism.html “Postmodern Philosophy” downloaded Feb 8, 2014 from en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postmodern_philosophy “Postmodern Religion” downloaded Feb 8, 2014 from enwikipedia.org/wiki/Postmodern_Religion Sklar, S. (Apr 25, 2011). “10 Key Characteristics of Postmodernism” downloaded Feb 8, 2014 from www.allvoices.com/contributed-news/8892593-10-key-characteristics-of-postmodernism Taylor, J.R. (Oct 11, 1988) quoted in Gombrich  Many weddings are all about the photo album. Since they are supposed to be about something else we can say this is as case of diverted significance. Weddings have been occasions of significance in almost every culture and era that we know about, and pretty much all of them have distorted the significance and diverted the focus. I’m thinking of creating one of those photo-montages popular on the Internet these days. “My Wedding” it would be entitled. “What I think it is” would be the caption for a picture down from the ceiling of the Salzburg Cathedral of Maria’s wedding to Captain von Trapp in The Sound of Music. “What the pastor thinks it is” (God smiling down on the couple piously praying). “What my father thinks it is” (a little girl breaking out of her father’s grasp and running toward a runny-nosed little boy). “What the groom thinks it is” (a long line of people bringing presents). “What it is” (Cecil B De Mills commanding a team of technicians and photographers). In India the wedding is so important to a family’s social standing that some families are bankrupted to put it on. In Japan an elaborate wedding day may involve as many as 10 costume changes. The Northern Thai wedding itself begins with a groom and his supporters and family making a boisterous trip to a bride’s home. The short walk is blocked at several points by the bride’s kinfolks holding gold or silver chains or ropes across the path, demanding a toll. Finally, the bride and groom are together, usually seated behind a low, small table. A person of status gives them each a floral lei and ties their heads together with coronets of string. The elders come, led by someone who has prepared an exhortation in verse covering the main aspects and goals of married life. The couple then pays respect to their parents and the parents bless them, which is really the heart of the wedding. The grandparents and elders come forward and tie strings around the wrists of the couple while wishing them health, prosperity, offspring and happiness, sometimes in forms of a chant, always with hyperbole such as, “May you live a thousand years and see your great, great grand children….” Then the couple is escorted by their parents and elders to a bedroom specially decorated with flowers where they are symbolically bedded, before the wedding dinner and party begin. But a casual observer would be forgiven for concluding that the main purpose of every aspect of the wedding is to create photographs. The project normally begins weeks ahead, when the couple spends a day or more and a lot of money having glamorous pictures taken in settings as spectacular and varied as the photography team and the couple can arrange. The effect is entirely imaginative. The costumes for these pictures are usually rented. The venues are conjured up for their scenic value with no regard for relevance to the lives of the couple or their families. One of the photographs is then turned into a major wedding portrait to be displayed during the wedding and on invitations, booklets and, of course, on Facebook. Other photographs are used to produce a wedding album, which is the central relic from the wedding. As many snapshots as can be recovered from the couple’s past, as well as all the professional pictures, are converted into a romantic video that implies the couple were lovers and meant for each other since the dim past, perhaps even before either of them were aware of it. This, as has been said, distracts from the wedding’s purported focus. In North Thailand the reason for a wedding is to proclaim two clans’ decision about creating a family, and demonstrating agreement about this on the part of the larger society. Why this photographic hijacking of such a solemn undertaking is tolerated and even encouraged is connected to the universal consensus that constitutes this individualist, post-modern age. To some extent postmodernism rejects the idea that there is a unifying theme or even strains of meaning more important than disparate perspectives of diverse individuals. In other words, the clans’ roll in the wedding is being subjugated. In Northern Thai society the marriage is still the union of two clans, but the wedding has been diverted to reflect wider cultural values. This opens the door for a woman to expand her wedding day into the greatest day of her life and to preserve it as her legacy for posterity. Notes: thanks to our niece Aem and her husband Nat for the use of their wedding portrait and for giving us the honor of hosting their wedding at our house in 2012. This is the third of four blogs on coming to terms with the ¨selfie¨ generation. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed