|

“Thailand” means “land of the free”. The phrase was coined by HM King Rama VI (1881-1925) to celebrate the fact that the country had escaped colonization by the French and the British. The name of the country was officially changed from Siam to Thailand in 1939 in a wave of patriotic fervor. Officially and by overwhelming popular opinion “Siam was NEVER colonized.”

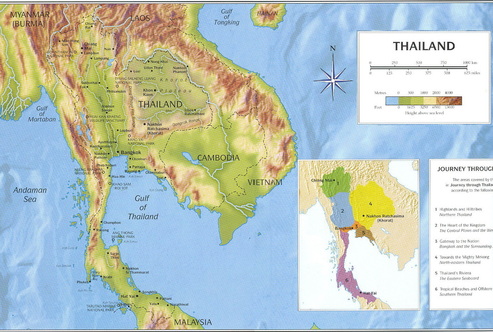

That is not to say the country escaped unscathed. In 1860 the Siamese Empire consisted of the central region that had been the Ayutthaya Kingdom until April 7, 1767 when the city was sacked by the armies of Ava (Burma). But the Burmese withdrew and did not colonize Siam. The kingdom was restored by King Taksin the Great almost immediately. From 1800 to 1860 there were five levels by which city-states and principalities were attached to Siam. Some areas were semi-independent with military protection agreements, others were vassal states, and some were attached through historical loyalty. It was complicated. But the total area of the Siamese Empire included everything from the Shan States to Penang, all of Laos, and Cambodia. Siam was the largest entity in mainland South East Asia. Then came the French and the British. Both of these European empires wanted access to China. Since the front door to China along the Pacific coast was hard to penetrate, the French wanted in the back door, up the Mekong River into the southern region of China. Step by step the French acquired the whole Mekong watershed, by disconnecting Bangkok from its allies and by naked gunboat threats. The British were after trade rights and protections of its privileges and colonies. They acquired Muslim sultanates from Siam in exchange for various agreements, and the Shan states for a promise to guard Siam from any more French warships. By 1914 Siam had lost half the territory once attached to it. Half its empire was colonized, but technically not the central part and the city-states in the Northern Lanna and North Eastern Isan regions that were Siamized and incorporated into the centralized administration run from Bangkok. Thus ended the dream of having all Tai people united in one country. [Resource: Wyatt, D, 1984. Thailand: A Short History. London: Yale University Press and Bangkok: Thai Watana Panich Co. Also see my essay “Protestant Influence in Siam” under the heading Life in Thailand on this website]. Then on December 8, 1941 Japan began its attempted conquest of South East Asia, including an air attack on Thailand’s military base in Prachuap Kiri Khan. Technically, Japan negotiated a military agreement to gain access through Thailand to Burma and India. Records show that the Japanese gained access to anything they wanted. This was not colonization, the propaganda of the times insisted, but the end of European colonization. This raises the question of what Thailand’s patriots mean by “free”. How is “free” different from something less than that. It looks to me like the key elements are that the Chakri dynasty has not been removed (as the British did in Burma), the government is still in Bangkok and includes no acknowledged major non-Thai interference, and Buddhism is the identifying characteristic of the culture. In Thailand “free” means these three institutions are intact.

0 Comments

Why do Christians pray?

For a large majority of Christians the question is dumb. Its answer is simple and self-evident. Why Christians pray would be about the same as why Buddhists and Hindus pray. Christians have Jesus’ instructions about prayer: “When you pray say, ‘Our Father, in heaven...give us...forgive us...lead us...’” Christians pray for the things they need to live abundantly and the attitudes they need to live faithfully according to God’s will. That leads to the underlying question of why Christians need to pray. Is God going to be passive until Christians implore their necessities? That doesn’t comport with the notion that God is loving as well as all-knowing. Does God withhold abundant life from those who do not pray, who are too little to pray, who pray wrongly, or who pray to other gods? In general, that seems hard to demonstrate. Plagues, drought, floods and illness as well as sunshine, kinship and welfare tend to come to populations indiscriminately. Innocent people sometimes suffer and guilty people prosper. Either prayers don’t work very well or the way prayers function is not direct cause and effect. That leads to the on-going discussion about prayer. Karl Barth, one of the 20th century’s leading Christian theologians, concluded that the only legitimate prayer is thanksgiving. Just the other day a friend from Toronto mentioned that prayers in the church he attends are positive, “no groveling in guilt and pleading for mercy.” An Internet posting informed me that the Church of England has mastered the art of prayer so as to remove the possibility that a priest’s indigestion will affect the contents of prayers. My friend and former colleague, Philip Hughes, a sociologist of religion in Australia, draws attention to a paradox embedded in Christianity as well as Buddhism. “The world is seen as both chaotic and governed.... It is negotiated both through calling on supernatural powers and through moral merit-making” [or obedience to God’s will, which is often the Christian equivalent of merit-making]. Philip and I tend to agree that most Thai sermons, Buddhist as well as Christian, are authoritative about moral and religious performance. That does not account for that which is random, chaotic, and supernatural. But the unaccountable elements in life are incorporated in faith practices when the sermons are over. In the picture accompanying this essay Saman Chaisatan a faculty member of the McGilvary College of Divinity at the time the picture was taken, is leading a group of seminary students praying for Elder Saikaew of Lampoon. It is probable that they were trying to be both realistic and optimistic, and that their prayer was intended to give the elder encouragement as well as to express confidence that God would do the optimal things to provide comfort and to address the infirmities and insecurity of the ailing church leader. In other words, Christians tend to shift into a supernatural mode of belief when dealing with big trouble. Philip puts it this way, “I believe that there is, in fact, a lot of 'supernaturalism' in the popular expressions of faith among Thai Christians. The ways in which people pray, their expectations of miracles, the ways in which they talk about God, all suggest to me that some of the thinking about spirits has been transferred and infinitely expanded to cover the idea of a 'Great Spirit' who has power over all other spirits ... to whom one can transfer one's allegiance and seek patronage.” I agree with Philip, and I remember Karl Jung’s conclusion that should modern theologians ever succeed in removing the element of mystery from Christianity, the religion will crumble into dust. From where I view life here in the valley, neither Christianity nor Buddhism is in danger of that happening. What’s going to happen when Lon retires? He has had a small heart attack and is getting older. His children are about the age to take over or at least to begin to help out, but he has two girls who are getting an education to escape that fate. In fact, in all of Pramote and Lon’s clan, there is not one candidate to take on farming the family acreage.

A generation ago, when Lon and Pramote were little boys the family owned a water buffalo. She provided the muscle-power to pull the plow. About 20 years ago the buffalo died and Lon and his father got by with a borrowed machine to pull the plow. The tractor Lon is using in the picture above was bought when Lon and Pramote acquired more land to be plowed about ten years ago. It takes three passes to get a rice field ready to accept transplanted seedlings. Rice farming in the traditional way is labor intensive. Lon has been working all day from 9 this morning until 5 this evening and he is just getting done with the first plowing. The area is a little less than 2 rai, or about 8 tenths of an acre. One of these days he will have to hire the plowing done. We offered to do that today, but Lon refused. Sometime, of course, he will not be able to do the second round of cultivation either, or the planting, or the harvesting. It will all have to be hired done. As it looks, that would eat up the income from the land. It would be cheaper to buy rice to eat than to hire the work done to grow it. Lon will be retired by then. Predictably, the next step will be for Pramote and Lon to sell the land. That will be the solution for the family. But what about the wider society? In all the villages around here there are few people between the ages of 15 to 30 who aspire to be farmers. The generation between the ages of 30 to 50 is the last generation to have enough farmers. They are supplementing their incomes with part time work in construction, village-level governmental positions, or crafts. When the next generation reaches adulthood they will have salaried positions and live away from here. Not only agriculture, but village life will change radically, and by that I mean it will cease to be community oriented. The social and cultural ramifications could be staggering. An image of the Lord Buddha undergoes an impressive ceremony to begin its service inspiring reverence and evoking peace. At the climax of the ceremony the eyes of the image are symbolically opened. One of the best ways to understand the significance of Thai images of the Buddha or of the temple in which the image resides is to comprehend what the dedication ceremony means.

Dr. Kenneth E. Wells was a Presbyterian missionary in Thailand. He made a study of Thai Buddhism his avocation and in 1938-9 wrote what is still the most comprehensive and authoritative description of Thai Buddhist practices in English. He built his study around field observations which he supplemented with references to available texts in various languages. When his book Thai Buddhism was reprinted in 1960 and issued in Thai it became a standard reference work for Buddhist monks as well as the general public. He described a night-long dedication at Wat Tha Satoi, Chiang Mai in February 1937. Within the vihara was an altar with about two dozen bronze images of Buddha, and behind the altar and along the wall were four larger images made of brick and mortar covered with gold leaf. A sincana cord had been wound about from one image to another and one end of the string brought to the monk in the preaching chair. Most of the images were new and many of them had been brought from private homes to be consecrated in this Suat Poek ceremony. The eyes of the new images were sealed with wax and a cloth of white or of yellow was placed over the head and shoulders of each figure. The worshipers, seated on mats, extended from in front of the altar to the door of the vihara and even outside filling the portico in front. [Wells describes the night long series of chants.} The selections were intoned rather than read, and so chosen that the final chapter, recording the death of the Buddha and his attainment of Nibbana, was completed just before dawn. At this point a monk opened a window shutter revealing the first faint streaks of morning light to the group within. The monks then seated themselves facing the altar and the leader chanted the “Presentation of Incense and Candles” (thavai dhup tien). Then followed the “Consecration of the images of Buddha,” or Buddhabhiseka ceremony. In this the Namo and Saranagamana were chanted, followed by the Dhammacakkappavatana Sutra. Then the Buddha Udana Gatha was used and a portion of the Vipassanabhumi Patha. As they chanted “Whenever the Dharma is made manifest to a brahmana who is diligent, such a bramana can ward off Mara with all his attendants like the dawn drives away darkness and fills the air with light” a monk arose and led a few of the laity in the task of unveiling the images and removing the wax from their eyes. As the vihara faced east the eyes of the images were thus opened upon the first rays of the rising sun. This Buddhabhiseka Ceremony was spoken of as an ordination ceremony whereby the images entered the priesthood. Prior to this service the images were considered to be simply statues, after the service the images were “phra”, something worshipful and more than metal. They had become sacred and possessed of mana or spirit of intelligence. At the conclusion of the ceremony the khao madhupayasa or celestial food was placed before the newly consecrated images. (Wells, Kenneth, 1960. Thai Buddhism. Bangkok: The Christian Bookstore. Pp. 127-8) Wells provided two valuable references as footnotes to his text: The origin of this ceremony is found in India. There when a man has purchased an image, “It is his invariable practice to perform certain ceremonies called “Pran Pratishta” or the endowment of animation, by which he believes that its nature is changed from that of the mere materials of which it is formed and that it acquires not only life but supernatural powers.” L.S.S. O’Balley, Popular Hinduism, Macmillan & Co., New York, 1935, p. 26. In Cambodia images of Buddha are likewise consecrated by a ceremony in which the eyes of the statue are opened. “The Acaraya takes scissors and pretends to cut the hair of the statue. He does this three times, and each time he recites a Pali stanza called Pheak Kantray .... He then takes a razor and pretends to shave the head of the Buddha [as takes place whenever a man is ordained]. He does this three times and recites a stanza of Pali called Kamboet Kor .... Then he takes two needles and places them, one on the left hand and one on the right of the statue .... Then he takes the needle resting on the left hand and pretends to pierce the right eye of the statue; then he takes the needle on the right hand and touches the left eye with the point. All the worshipers then cry out three times in Pali, ‘We have now happily opened the eyes.’” Adhemard Leclere, Le Buddhisme au Cambodge, Paris, Ernest Leroux, 1899, p. 369. I have attended a dedication ceremony which included opening the eyes of the Buddha. It was missing the dawn symbolism, taking place within a two hour period in the evening. The meaning was the same, and no doubt has been the same for centuries. In the picture accompanying this essay, we see our friend Than Daeng lighting candles and incense. The Buddha image is made of bricks and mortar, completed by the monks seated before the image. Its eyes are covered with yellow wax and the head with a white cloth sack that will both be ceremoniously removed. Thus is the Lord Buddha awakened and invested with mana, animation. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed