|

I believe there are three phases of retirement.

The FIRST PHASE is usually what one is being chosen to do. For many of us retirement is a formal step when one can begin to collect accumulated funds set aside for this time in life. It does matter that one passes a mandatory date when one’s options begin to be set by rules. However, many of us have extended careers for which we are recruited. It is good advice to not just “retire from” but also to have a plan that includes “retiring to” something meaningful. Examples: A good friend of mine retired several years ago but has continued in the very same position until this week. She will now be entering phase two. Another good friend would have liked to continue in his position, but did not get a chance to do so. He took a series of short-term positions that were equivalent to his life-long career. A pastor in Illinois retired to do interim pastoral stints. I have heard of a man who retired from a career with the railroad to run a model railroad in the St. Louis Zoo. Exceptions: Some people begin this sort of consultancy or interim work before getting to the age where compensation is secondary. I know an engineer who took a “golden parachute” into retirement at 45 years of age, and now is a free-lance engineer with his own company. Some would say he has not really retired, but his portfolio says he is independent. My dad skipped this phase and went straight into full retirement. The SECOND PHASE is what one chooses to do. This is often thought of as “real” or “full” retirement. It may be entirely different from one’s professional career. Hobbies and social relationships can become the focus during this phase of retirement. It takes mental and spiritual dexterity to discover something significantly meaningful in the midst of a plethora of activities that are plainly enjoyable. Examples: My dad retired to go fishing. Many go fishing in retirement, but Dad retired in order to do it. He made that his main endeavor for several years. A former pastor of my home church retired to do landscape painting and to write articles for church journals. I am now in this phase and I have written everything I planned on writing when I fully retired, and am now writing just for the fun of it. I believe my brother and his wife can be said to have entered full retirement in order to travel around to as many state and national parks and forests as they can. That’s Dan, my brother, in the picture above. Exceptions: Some people have a chance to choose to do what they have done in some form or other so the line is blurred between phase one and phase two for them. Others go from phase one (continuing to work) into phase three, due to a sudden medical crisis. I know of a couple whose carefree plans for retirement were abruptly changed when they had to take over raising two more children. The THIRD PHASE is what one has no choice about. One always has choices, but when the range becomes limited by what works best to handle health and physical circumstances, one has come to the third phase of retirement. Phase three is when the controlling factor is how to handle one’s health and safety. For some, this means a change of residence, but for others it is more a change of perspective. The greatest challenge is to ascribe meaningful significance to this phase of sustaining one’s self. Only those who have developed a solid spiritual base can do it. Examples: Mom spent several years as a senior-citizens’ ombudsman, after retiring from teaching kindergarten. The time came when she just took a room in the retirement center so her meals and medications could be handled dependably. The wife of a good friend from long ago is now in advanced dementia and her life is supported and sustained by professionals. A friend here in town has just moved into “assisted living” after falling several times and being unable to get back up, once in the bathroom where he could have drowned. A lot of retirement institutions have 3 or 4 levels of care to accommodate levels of need. Exceptions: It is quite obvious that some people need assistance and support long before getting to an age that could be called retirement. That is, medical and physical circumstances can begin to compel responses at other times in life. “Normally”, we think, we will get old before we have to rearrange our life plan to handle things like that. Many of us, like my dad, never get to phase three. He took his medicine and didn’t let his health concerns impact his plans to go fishing in the warm south. For others, as is the case with Pramote’s father, extended family provides nearly constant care. But his life is impacted by his health and his daily life is bounded by these issues. Let me insist, however, that it would be very wrong to think of phase three as terminal or lingering. Phase three has just as many thrilling and fulfilling possibilities as other times of life may have. CONCLUSIONS: It has been helpful to me to think of retirement as having three phases. But as with other discussions of ages and stages in life, there are exceptions. Even more frequently, there are incremental steps from one phase to another. Finally, age is an artificial measure of one’s progress through life. It is conditions and circumstances that matter most. POSTSCRIPT: What are coming generations going to do if they are prevented from developing the capacity to build toward retirement? The rules are changing. It is already almost impossible in the USA for those in their career prime to accumulate funds to manage the sort of retirement I have described.

0 Comments

“Are you unique? Are you special?” the teacher asked his class. They thought they were. “Yes, yes,” they chorused. “Of course we are!” How absurd to question our individuality. It’s a basic human right isn’t it? It’s a basic assumption, anyway.

We who are LGBTIQs will probably be among the first to insist that each and every human being is unique. It’s the basis for our argument that we are entitled to equal treatment with heterosexuals and celibates. “I don’t need to be like you.” “I am who I am,” or “I am who God made me,” or “I am gay because my karmic destiny led to this.” We need this rationale. “No,” the professor responded, “you are not unique.” His argument was that overwhelmingly we are the same. Biologically, physically, psychologically we are far more alike than we are different. Our range of head sizes is hardly more than an inch different. Our number of any physical organs, their size and function is normally the same. Our life expectancy, the environment in which we most easily thrive, or the way we will succumb to viruses, in all these ways we are alike. Where did the idea come from, then, that we are discrete, diverse and different? Like many of our most passionately held persuasions the concept is not particularly old. Throughout most of human history individual rights were unheard of. Rights, rules and regulations were not structured until the second half of recorded history and the individual was not singled out until much later. In the West it was the Enlightenment, just 500 years ago, that placed special emphasis on the individual. In the East it was the coming of the West that initiated the idea, still not very widespread, but growing. The teacher’s point, however, was that the major beneficiaries of the idea of individuality are the manufacturers of products. It is they who profit from our desire for wide choices of hair styles, foodstuffs, and fabrics. How many types of sneakers does the human race need? He was convinced that this was all part of a vast conspiracy with potentially disastrous environmental consequences. It’s a thought-provoking idea, and we can see how it applies to the gay side of society. Here in Thailand there are now a couple of gay oriented lifestyle magazines and several more aimed at “metrosexuals”. From them we are meant to learn how our trend leaders dress, what they eat and where they go to express their natural desires, so we can be more like them. But wait a minute! These guys are not like us…not most of us. They are all physical hunks, under 35, with perfect complexions (not counting tattoos), and extensive expendable funds. They are not us, and they know it. They are disdainful in their expressions, attitudes and actions. They suppose they are who we are supposed to be. And we suppose so, too, if we aren’t careful. They are our trend-setters and role models, and if we are too old, too fat, too dark, too anything – we need products to compensate. We need ointments, clothing, services and activities to make up for our sorry deficiencies. Obviously, this is a marketing ploy and it is used to manipulate various sectors of the marketplace, not just us. The teacher was right about that. Still, I am not yet convinced that the thing to do is to protest against the place of the individual and advocate the sovereignty of the group. We’ve been there and suffered from it. The tyranny of the majority is sometimes against US. So, how do we sort this out? We need to affirm our membership in the human family. That could be our metaphor. We are all part of this family. But we are not identical, nor clones. Although largely alike we are not entirely alike. Our DNA is different, our fingerprints are unique and our personalities are diverse. We are mostly like everyone and even more like kinfolk, yet we are not like anyone else except in certain apparently random aspects not of our own choosing. On the other hand, if we are to be gay we need to set ourselves apart, express our individuality, dare to be proud, and find our place in the world. It is particularly urgent for us gay men to defend our niche in homogenous humanity. There are ways in which each of us is more like certain groups of total strangers and distant foreigners than we may be like our next of kin or closest ancestors. That, in fact, affirms our membership in the whole human family, and it is what moderates our identity as individualists. Keep your wits about you, as my grandmother used to say. Don’t be shoved into behaviors that are wrong or optional, which are not of your own choosing. You can’t buy your way into significance. Being gay has no connection to brands of underwear. And styles of briefs have no impact on happiness. Or most of the time it does not matter. [This essay was based on an initial idea supplied by Louise Jett and written in 2012 for OUT in Thailand magazine edited and published by James Barnes.] See also: www.kendobson.asia/blog/spectrum TALKING ABOUT THE BOYS IN THE CAVE CAN GO WRONG

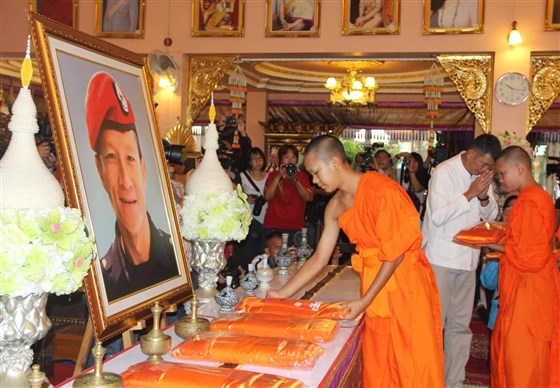

My friend, the Rev. Gene Borquin sent me an August 4, 2018 article in Episcopal Café, about the rescue of the 13 fellows trapped in the cave in Chiang Rai, Thailand. He asked for my response to “the Episcopal article.” The article was rather like daily devotional literature, meant to inspire reflection. Here is a link to the article by Amy Shimonkavitz, a lay preacher and a postulant to the Diaconate in the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland: https://www.episcopalcafe.com/the-way-out/ The author reminisced about how she reacted to the drama of the 13 boys trapped in the cave for three weeks. Some of her experiences reminded her of Christian truths, she said. She talked about those. As she went on I began to wonder whether her reflections were valid. How does one evaluate an article or a sermon that describes a meditation? She essentially did what we all do when we preach based on a true-life story. There are three ordinary steps which she followed. She recalled the narrative accurately in ways that she could reasonably assume her readers could agree was what the story said. Then she gave testimony about how the story had resonated with her, personally. She mentioned emotional points and triggers. As she got these two steps firmly enough behind her she attempted to universalize in ways that she hoped her readers would perceive theological principles. She thought she found why we were hooked on the story. “This is the story of our own rescue.” “Our hearts echo with the same joy of being found.” That’s why we were so enthralled with this unfolding saga and its marvelous outcome, she said. The question I would raise is, “Did she actually catch anyone on her hook?” Is it true that the reason we were glued to our TVs and computers during the days-long drama is because we felt echoes of our own salvation story being dramatically re-enacted? The unfolding saga mesmerized nearly the entire Thai population and resulted in what is surely an unprecedented massive response by Thai officials who were not acquainted with the Christian narration of salvation, but were responding as humanitarians. But I’ll cut her some slack on account of her obviously writing for Christians who are at least supposed to have joy at being found like the lost sheep. She tied those echoes of joy at the boys’ rescue rather clearly to the Christian interpretation of salvation, including atonement involving the death of Christ. Did the death of the former Thai Navy Seal “recall Christ’s own sacrifice for us in the mission to save us from sin and condemnation”? I cannot question that it did recall Christ’s sacrifice for her. However, I am confident that not everybody made this connection. I think her recitation was manipulated at least insofar as its validity depends on those who are rescued being a type of those who are saved from sin and condemnation. The allegory breaks down at this point. I would argue against saying it was due to sin that the boys went into the cave and got trapped in there by a natural phenomenon. I would argue even more against the suggestion that Navy Seal, Saman, was doing what Christ did. Saman did not single-handedly reverse the outcome that was otherwise in store for those boys. Saman was part of a massive effort that was impelled by a united humanitarian impulse. What Saman was doing was a help, but his death neither defeated nor completed the rescue. He was not a Christ figure. Amy would have been more on target if she had compared the rescue effort to the Good Samaritan. Her analogy also failed when she talked about what the boys needed to do in order to be rescued. She called it “repentance, turning back,” and said it’s “never easy.” Well, getting the boys out was certainly not easy, but it had little in common with repentance and turning back. It was much more like going on through conditions they had never encountered before. She said, “The boys needed blind trust” in the Navy Seals. (The key rescuers were not all Navy Seals, but never mind.) Actually, because of concern about a panic reaction, the boys were anesthetized as they were brought through the flooded cave. Once they were unconscious, trust on their part had nothing to do with it. It was the rescuers who had to have trust that their calculations and preparations were right, that nothing unexpected would go wrong. The planning was meticulous and left as little to trust as humanly possible, the rescuers told us in post-rescue interviews. Allegories always fail to catch the essence of a universal principle, whether it is theological or otherwise. Rigid allegories fail spectacularly. Amy wrote a soft sort of analogy that did not try to extract every drop of truth from the narrative or even try to identify the central truth. She settled on how the story of the boys’ rescue moved her to tears and prayer and brought to her mind Christ’s rescue of her. All of us preachers preach, but not all of our sermons are grand. Great preachers are rare. They exceed the rest of us in their ability to find the central truth of a narrative and then challenge those they address to measure their response by the ideal discovered in Jesus the Christ. So her homiletical essay was almost OK. My response is that she intended to be uplifting for her readers in Episcopal Café and she succeeded. She reached that point about half-way through paragraph five. However, when she went on to tell us that the reason we were moved is because we realized that what was going on in the cave rescue was parallel to what was going on with Christ, she invited dissent, which undoes inspiring uplift. As soon as I say, “Whoa! Few of the people I knew were making that connection with Christ’s sacrifice and the Easter salvation message,” I stop being inspired and began to doubt what it was she said that held the world enthralled. She was wrong in her main assertion. Our emotional involvement in the boys’ rescue was not because “this is the story of our own rescue.” It may be parallel to the story of our salvation, but that’s not why we wept tears and prayed. The reason we did that is deeper in our human nature than a cognitive theological construction. The parents of those boys cried and prayed because it was their sons in there. Many of the rest of us cried and prayed because those boys were suffering and their chances were slim and we felt desperate for them. Amy distorted almost everybody’s profound emotional involvement and cheapened it by describing it as a metaphor for something intellectual. For most of us, this cave drama never became about anything that had ever happened to us. Not even those of us who had had near death experiences thought what was happening to the boys was very like what we’d been through. Even the rescuers insisted that this was unique in human history. No boys that age had ever been forced to do what they had to do to get dragged and carried out of the cave. A theological concept is derived from and not the cause of involvement in something profound that comes to be seen as a divine-human encounter. Theologizing is second-step or second-level. It is one step removed from raw experience. It happens when experience is processed, and that is culturally informed. [Pictures from various news sources show that the boys were not “processing” their experience into a Christian religious formation. Hardly anybody in Thailand was doing that at the time.] Overenthusiastic theologizing discredits Christianity, and this is the wrong time in history to keep on doing that. The more I think about it the less Amy’s analogy holds up. REMINISCENCES

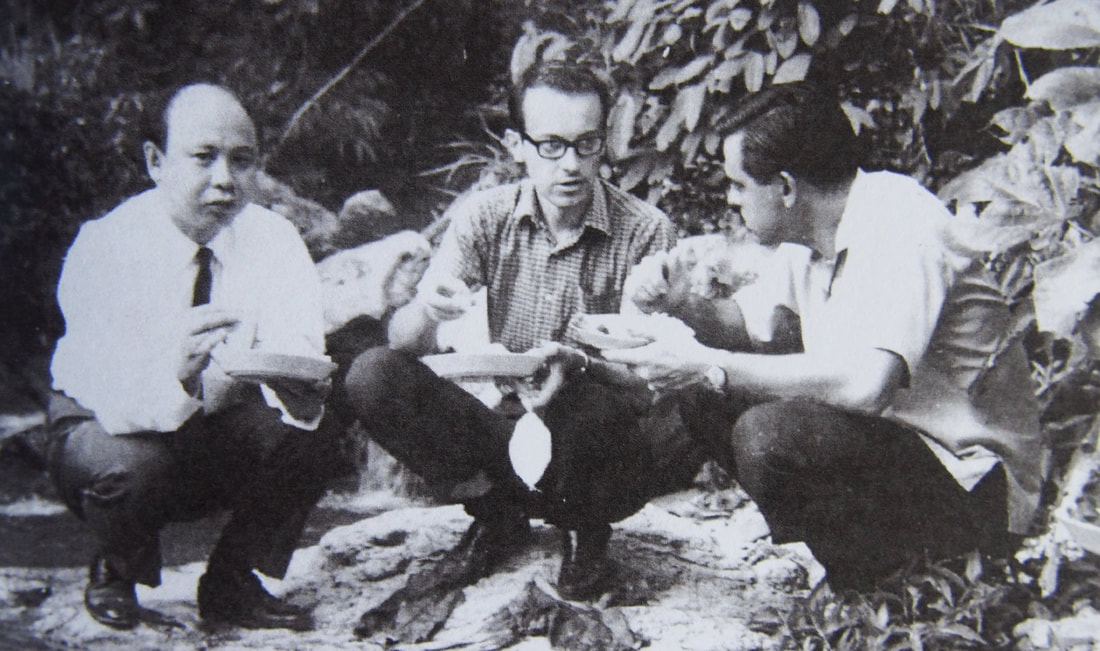

Shane asked, this week, for people who were missionaries in Thailand during the Vietnam War to tell how our work was affected by the war. I was a United Presbyterian Church (USA) fraternal worker in Chiang Mai, Thailand from August 1965 to June 1969. My duties included teaching “theological English” at the Thailand Theological Seminary [which is now the College of Divinity of Payap University] and at other nearby schools of the Church of Christ in Thailand. Superficially, the escalating war in Vietnam did not affect our work as missionaries or the mission of the CCT. But the war was a pervasive issue in the background, a background which also included profound changes in Indonesia, Communist infiltration into Thailand, and the Maoist Cultural Revolution in China. World War II was a personal memory of several of our missionary colleagues including Ken and Margarita Wells who were just retiring from long-term service in Chiang Mai. A number of other missionaries in Chiang Mai were transferred here when the Communist Revolution fully took over mainland China. These missionaries and those who came after the war to rebuild the church infrastructure of schools, hospitals and churches were heavily influenced by the specter of yet another anti-Christian military-political apocalypse. The longer the Vietnam War lasted and the more it expanded into the rest of former French Indochina the darker grew the shadow over Thailand. By the middle of my 4 years in Thailand other areas of the country were being heavily impacted by the construction of air bases and naval facilities and especially by the influx of large numbers of US military personnel in and around Bangkok on short leaves for R&R. Even in Chiang Mai, military developments were coming into view. Air America planes were parked at the airport and we knew they were not for commercial use. On the lower slopes of Doi Suthep a seismic and meteorological monitoring station was built and staffed by the US Air Force working alongside Thai Air Force personnel. Those US personnel lived in town, and although few in number, were our age, so we got to know some of them. Also, higher ranking USAF officers occasionally moved their families to Chiang Mai to be nearer, but not too near. Up to this time there had been an English language worshipping community composed mostly of missionaries who attended Thai churches on Sunday mornings but gathered for worship and fellowship in the evening, and for Bible study once a week. The addition of new US military families was one factor that prompted the community to consider forming a full-fledged church congregation as was already the case with International Church of Bangkok. The Rev. John Butt and I were designated co-pastors of this new Chiang Mai Community Church while a committee looked for a full-time pastor. The Rev. Douglas Vernon was recruited in 1968 and he and his lovely, vivacious wife Dot moved into a rented house on the Ping River right across from the US Consulate. One of the activities of the Chiang Mai Community Church was to host Religious Retreats for US military personnel, which were alternatives to free-for-all R&Rs the military provided. Bob Bradburn (Presbyterian) and Jim Conklin (American Baptist) coordinated these retreats with chaplains who wanted to have them. Bradburn and Conklin worked out the program with the chaplains and then recruited us to help provide what was needed, including Bible studies, worship services, tours of mission work, Buddhist temple tours, talks by Buddhist monks, visits with Thai church leaders, pot luck suppers or overnight home stays. One of the goals was to give these military service personnel insight into ordinary Thai life to counter the jingoistic opinions that tended to develop among them. One of the themes that Bradburn and Conklin tried to convey is, “This sort of freedom and culture is what is natural here and worth defending.” We got high praise from the chaplains and anecdotal accounts of changed attitudes from some who had attended the retreats. Overall, these were addenda to the mission work each of us was doing. What we were doing, we believed, was supportive of the mission and ministries of the Protestant Church in Thailand. We were involved in building peace, a more important and full-fledged peace than others were building, and without strategies that annihilated people in order to save them. At the same time, due to new American children of USAF families in Chiang Mai, the Chiangmai Coeducational Center expanded from a small school for missionary children with a dormitory facility, into a larger “American School” that became Chiang Mai International School. In lieu of direct tuition to offset the increased class sizes and need for staff, the CCC board negotiated with the US Consulate to provide a teacher starting in 1966. We can say that the impetus for expansion of the little mission school into an international school was a result of the US military presence in town. CCC became the first of several international schools in Chiang Mai. In my opinion, it is the most lasting physical change to missionary objectives. Of course, it too would have faded with the end of the Vietnam War and the relocation of military personnel except for tourism and the nation’s new willingness to have the economic advantages of expatriate long and short term residents. The increase of expats living in Chiang Mai has been exponential and that has included what amounts to an open door for missionaries of a bewildering variety. That, too, I believe is the direct result of what was going on beginning in the 1960s. [Thanks to Gerry Dyck for this picture of 3 seminary teachers who helped with Religious Retreats for US military personnel. L-R Ken Mochizuki, Ken Dobson, Gerry Dyck. The picture appears in Gerry’s memoirs: Musical Journeys in Northern Thailand, p.37] |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed