|

Corporate memory often frazzles. Institutional memory is a fragile and devious thing.

Institutions often last much longer than individuals who establish, maintain, and inherit them. Educational institutions can outlast even governments and dynasties. Institutions are sustained by successfully including an influx of new leaders. This is best when it is incremental, allowing new leadership to absorb the accumulated knowledge and unique traditions, as well as the memories of trends, events and people in the past. Meanwhile, institutions need to keep up with the times. An incoming CEO or president has a delicate line to walk between aggressively pursuing change that may have been delayed and alienating significant persons whose commitment has been refined to focus on institutional aspects the new leadership is marginalizing. In pondering my status in the institutions with which I have been involved over the past 70 years, it is clear that I am now largely irrelevant to most of them now. Whenever I contact them or even show up on their campuses I am initially a stranger. Only the buildings feel like I might belong there, and usually not even them. Since I am outside those institutions, for all intents and purposes, I feel free to offer some advice. Few events that an institution experiences are dramatic. Institutions are developed one tiny increment and one decision at a time. In fact, spectacular events tend to be destructive ones that threaten the institution. Recovery is then the institutional task, and that means getting back to the tedious tasks of making little decisions. Those rarely restore what used to be. I remember one day after we re-constructed and re-dedicated the First Presbyterian Church of Alton, IL. The wife of the long-time former pastor was invited to visit as a chapel was dedicated in her husband’s name. She was not appalled at the changes we had brought after the fire had destroyed everything, but she let me know this was no longer the same church of which she had been a key member for a quarter of a century. The building was strange to her eyes, even if many of the people were not. Now most of those people are gone, too, as is she I understand. A couple of years ago I went back to that church after nearly a quarter of a century and the building felt the same, but the people, for the most part, were not. The programs were also different. Payap University, with which I have been associated in one way or another since 1965, has had 5 fully installed heads with the title president. Each brought a clear vision about what the university might become. Those visions were of Payap being a leading liberal arts institution, then as a new president took over the goal was for the university to develop into a comprehensive university, and more recently the president’s vision was for Payap to be the best international university in the region. None of those visions was fully achieved before perceived realities prompted it to be abandoned in place of a new vision. In the process, of course, a vast amount of institutional knowledge was rendered obsolete. Some of that wisdom stood in the way of progress. Last month I had lunch with a long-term university insider. His conclusion is that there is an institutional bias against change. Many universities and colleges stay with whatever they have always done even when it is no longer working, and spiral into oblivion (that is, usually, into economic un-viability). In other words, a large institution is too unwieldy and settled to adapt to change. On the surface, that seems to contradict my contention that institutions have trouble retaining institutional memory. However, I have noticed that resistance to change is not the same as institutional memory. The source of institutional conservatism is usually the collective will of institutional operatives to retain the positions and conditions they have worked to acquire. What is a German language instructor to do if German language courses are dropped from the curriculum? It is only natural that the instructor will try to avoid that. The institutional visionary, on the other hand, is exerting equal energy in proposing some bright alternatives to operations that have become unproductive or obsolete. The institutional historian is neither of these. The historian collects and remembers specifics, dates when decisions were made and reasons for those decisions, the gestalt of key moments in the institution’s history, the names and methods of operation of individuals who got major objectives achieved, and most of all what is the institution’s heart and soul. It is not unusual for each one of those three functionaries, conservators, innovators, and historians, to see the other two as obstructive. Of course, each of them is valuable if they work together. How to get that happy compatibility is a challenge. Conservators are not simply interested in self-preservation; they are institutional ballast without whom the institution would founder whenever it encounters sufficient turbulence. Innovators are most effective when they can demonstrate that new initiatives have already worked, and can incorporate the aspirations of the institution as well as the wider community and customers (by whatever name). Historians must be narrators who are so skillful that when they speak the institution listens, so they need to be the ones most often in the pulpit or on the platform when the institution gathers to ponder itself. It is by the cumulative weight of countless decisions that the institution has gotten where it is. It will take countless decisions, each one of them of little apparent consequence, to get the institution to where it is going to be.

2 Comments

Three years ago I watched a local Buddhist monk inscribe numbers onto small copper sheets to be installed under ceramic lions on gate posts. I described this in a blog-essay at the time (see www.kendobson.asia/blog/guardians). I knew the overall purpose of the process was investing the lions with protective power. It is the same as with tattoos.

What fascinated me was the special order in which the monk inscribed the numbers onto the plate. I thought it might be some form of “magic square” such as the Chinese discovered centuries ago. A nine digit magic square in the form of a tic-tac-toe # is like this: 4 9 2 3 5 7 8 1 6 Each of the lines and diagonals equals 15. Legends say that this pattern first appeared on the back of a turtle seen by a Chinese king, who used it to end a deadly threat. But the monk’s inscription was not a magic square. His figures were like this: 1 4 7 6 9 2 3 8 5 He explained that the chanting as he inscribed the numbers was a Buddhist stanza in honor of the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. It is, presumably, the same chant as is used in every Buddhist service. Namo tassa bhagavato arahato sammasambudahassa. Namo tassa bhagavato arahato sammasambudahassa. Namo tassa bhagavato arahato sammasambudahassa. We worship the Blessed One, the Self-enlightened One, Supreme Lord Buddha. We worship the Blessed One, the Self-enlightened One, Supreme Lord Buddha. We worship the Blessed One, the Self-enlightened One, Supreme Lord Buddha. That is followed by the three refuges, “I take refuge in the Lord Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha: Put-tang saranang kaj-saa-me Tham-mang saranang kaj-saa-me Sang-kang saranang kaj-saa-me Tu-ti-yam-bi put-tang saranang kaj-saa-me Tu-ti-yam-bi tham-mang saranang kaj-saa-me Tu-ti-yam-bi sang-kang saranang kaj-saa-me Ta-ti-yam-bi put-tang saranang kaj-saa-me Ta-ti-yam-bi tham-mang saranang kaj-saa-me Ta-ti-yam-bi sang-kang saranang kaj-saa-me Still, I was intrigued by the sequence in which the numbers were inscribed. After months of considering this I realized that this was not a square but a circle. The order of inscription was “1, skip two places going clockwise, 2, skip two, 3, skip two, 4, etc.” 9 went into the center. It was Buddhist, after all. It was the pattern for the wheel of the law. (See the wheel, above). But now I have discovered its antecedent in Jain religion, as are many of the esoteric forms of Buddhism. A longer discourse on these yantra diagrams is here: https://www.yoginiashram.com/yantra-harnessing-the-power-of-mystical-geometry/ Yantras can be rendered in flat designs as is the blue and white example and the painted yantra above. They can also be executed as tattoos. (The pictures of tattooing by a famous monk tattooist in Nakhon Pathom province, above, are from a Wiki article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yantra_tattooing ). Yantras can be two or three dimensional geometric patterns, but also represent the spirit of animals. Tigers, elephants and snakes are particularly popular. Yantras, we are told, are lifeless unless they are inscribed while a mantra is being chanted. The reason for this is, “Mantras, the Sanskrit syllables inscribed on yantras, are essentially ‘thought forms’ representing divinities or cosmic powers, which exert their influence by means of sound-vibrations.” I have been told that the holy Om is the most potent. Yantras can also be produced as mandalas. Mandalas tend to be much more colorful and elaborate, and therefore their creation is much more complicated. The most famous mandalas are Tibetan, including sand-mandalas. Above is a picture of the Chenrezig Sand Mandala created and exhibited at the House of Commons of the United Kingdom on the occasion of the visit of the 14th Dalai Lama on 21 May 2008. Synthesis: The relationship of mathematical numbers, especially mysterious patterns, to cosmic and physical reality has been a subject of intense speculation for centuries. Occasionally whole mystical, religious or philosophical schools have arisen around these theories and mysteries. The Pythagorean School was one of the largest and most sophisticated. European alchemists were another, as were Jains in India. In fact, every religion and civilization from Aztecs to Zoroastrians has expressed interest in the relationship of numbers (in the broad sense) to physical and cosmic reality. Usually it is numbers or harmonics that bridge the chasm between the mundane and the transcendental. Perhaps mandalas reside in our collective unconscious as Jung discovered, to be remembered and revised -- such as the street design a week ago in Alton, Illinois at the Mississippi Earthtones conservation festival (picture by my son Andrew Dobson). Meanwhile, some religions, Christianity being one of the main ones of these, go through periods of protest against investing physical symbols with mystical power of any sort. That, however, shall be the topic of another essay. The Kai Song food shop in Nam Bor Luang Village is our default place for a meal when Pramote has been too busy or tired to fix something. It is run by Kai (pronounced “guy”) and her life-partner Nong. They list ten or fifteen things they are ready to cook, but they can usually cook whatever you suggest if they have the ingredients. It is a “Food to Order” shop, as opposed to a noodle shop. The shop is, not coincidentally, right across the lane from a Thai massage school that has a constant stream of students from Japan. Kai and Nong were hired 10 years ago to be cooks for the school, and then they had a chance to open their own shop across from the front gate which expanded their clientele. They still provide food for the massage students who come for a week or two. It appears that Kai and Nong are well accepted in the village, and they are frequently visited by relatives.

I do not yet know how Kai and Nong found each other. I think they would tell me if I were bold enough to ask. But that is precisely the matter I want to consider. First, it is not customary for a couple to discuss openly how they met, how their relationship developed, and how they decided to make their relationship public. An invitation to a wedding typically comes as a complete surprise to almost everyone. It is not discussed ahead of time, as if that might jinx the whole thing, or bring shame on the couple if the marriage were called off. Even years later those early days of a relationship are kept private. Second, one thing Kai and Nong have in common with Pramote and me is an atypical relationship. I doubt that Kai and Nong are as “out” about their lives as are Pramote and me. We have gay parties and fly a rainbow flag (thanks to a gay couple who visited us a month ago), and Pramote is affectionately called “Madame” by half the people in our village. I have declared our house a sanctuary for any gay boys or girls who need a safe house, and I have published a book with the subtitle “Gay Experiences in Thailand”. But, as with Kai and Nong, the community at large has found a “neutral” category for us as a couple. It is ambiguity that matters. Ambiguity is important. Abandoning it is risky and almost always unnecessary. I think that is a very large difference between how society functions in North Thailand from how things work in North America. Third, all relationships are somewhat atypical. Each couple in Pramote’s family has a relationship that is unlike any other couple. Let me explain it this way: although Pramote and I are the only couple in the extended family who are identified as “same-sex”, our relationship is not as “abnormal” or “flexible” or “unstable” as at least two other couples. In other words, we are in some ways more typical as a couple functioning in this society than many couples who have or could have their marriages recorded at the district office. My point is, there is no point in designating who is typical and who is not. Pointing fingers is disruptive, impolite, and inevitably inaccurate. Kai and Nong are not “those lesbian cooks” but are simply Kai and Nong. Fourth, with aggravating regularity some asinine writer tries to make a hit by slapping a label on people in a gender genre. Just a week or so ago another ten-day tourist produced a video all about the wonderful “Ladyboys” he had found in Pattaya and Phuket. He imagined he was being complimentary. Those labels always diminish and segregate. Finally, it seems to me that the present disparity between LGBTIQ people like us and the rest of hetero-normative society will eventually be resolved by dissolving the sharp lines that are being made even more distinct these days in order to designate who needs to be included with rights identical to everyone else. As we who are familiar with Thai attitudes know, skin color in this culture is a matter of extensive attention. Never, however, has skin color been used to designate legal or even social rights. Gender identity will, I believe, fade as a factor determining rights, as well. This week marks the 17th anniversary of the destruction of the World Trade Center twin towers in New York City, as well as the ramming of the Pentagon building in Washington, DC, and a foiled attempt to fly a fourth plane fully loaded with passengers into the White House. The results were unprecedented destruction, live-action horror for two billion viewers on television, and nationwide trauma in the USA. The attacks on the morning of September 11, 2001 shook US national self-confidence but the immediate reaction was an immense outpouring of humanitarian responses, heroic actions, and compassionate solidarity.

9/11 (which ironically is also the emergency hotline phone number throughout the USA) is remembered by everyone who lived through it. Still, the motto “Never Forget” has evolved as the slogan for the day. The imperative to “never forget” raises the question, “Why would anyone think we would need to be reminded?” The slogan evokes poignancy and demands response. Forgetfulness is shameful and unpatriotic. Recently, however, the question has arisen, “Never forget what?” Exactly what are we being challenged to remember? Where we were when we saw the planes strike the towers on TV? How erratic the national leaders were at the beginning of the crisis? How horrible it was for victims trapped in the planes or the buildings? How heroic the first responders were? How dastardly the terrorist perpetrators were? The names of those killed? The involvement of Muslims? How all national divisions were forgotten in our moments of response? How helpless and vulnerable we felt? How our rage was aroused? All of the above? For the first ten to fifteen years we were expected to pick some of those memories and to hold them fresh before us every September 11. Now we have a new generation of young adults whose memories do not extend back to 2001. What are they being exhorted to “never forget”? This is not an entirely philosophic question because we are all being groomed to remember a time of collective trauma and response in a certain way. There is, I submit, a great deal more uniformity in our remembrance of the shock and horror that developed into collective trauma than there is to our responses. That is, the responses to 9/11 include some that we have polished and cherish and others that elicit doubt or shame. Our responses were diverse, including the campaign to get Osama bin Laden at any cost and wipe out the forces he recruited wherever they were hiding, and also campaigns to build a fitting memorial for those who died and to provide scholarships for their children. As we welcome the first post-9/11 generation into the conversation as peers we will need to clarify what we are to never forget. As a student of philosophy who grew up on Wittgenstein, I would like to point out that collective memory evolves and shifts. Icons are shifty and their manipulators are too. Consider the monuments we erect to preserve memory of collective trauma. The fall of the Roman Empire is memorialized in the ruins of the Roman Forum. The devastation of the Second World War is recalled in the skeletal dome at ground zero in Hiroshima. The Holocaust is poignant at the Auschwitz site. The US Civil War is symbolized by the Gettysburg graves and battlefield. Those memorialize horrendous loss which came to an end. Italy moved into a Renaissance nearly as glittering as Imperial Rome. Japan survived. Jews overcame. The Union re-unified. So it is safe as well as salutary to ponder the ruins. The ruins say, “We are not defined by that past.” In an ironic way, that is what the glowing hole at the site of the twin towers is supposed to do. It is trying to push our memories forward as well as force us to meditate on what was destroyed … lives (people with names) and spectacular property, the tallest and largest buildings in the world, the very symbols of American economic and military might. The terrorists thought attacks on these would symbolize the fragility of this form of American empire and humiliate us. But, behold, we survived that trauma. The threats against us were once again eradicated. We are essentially invincible. If that is what we are to never forget, we are going to have trouble keeping the conversation going when these new college age young adults have their 20 year-olds ask, “What are we supposed to never forget?” The fiftieth anniversary of 9/11 in 2051 will need a new lesson rather than American exceptionalism and invincibility. That sort of mega-narrative is unsustainable and it is unworthy. Up to now it has worked to just chant, “Never forget.” When everybody who is chanting has a vivid personal memory of that day it would never work to fill in the blank for them. We would retort, “Don’t tell me what to remember, I saw it happen.” The day is coming, however, when circumstances will no longer revolve around today’s targets of terror and pride. People of that day will “never forget” 9/11 at the same emotional distance as we “remember the Alamo.” It fits our narrative to remember the Alamo as heroic resistance to tyranny and eventual victory over huge adversity as a step in nation building. Davy Crockett’s agenda in the Alamo was more personal and existential. A new national narrative about 9/11 is coming, never doubt, and it will fill in the “never forget” frame with content we have not yet contemplated. 1. SPIRITUALITY

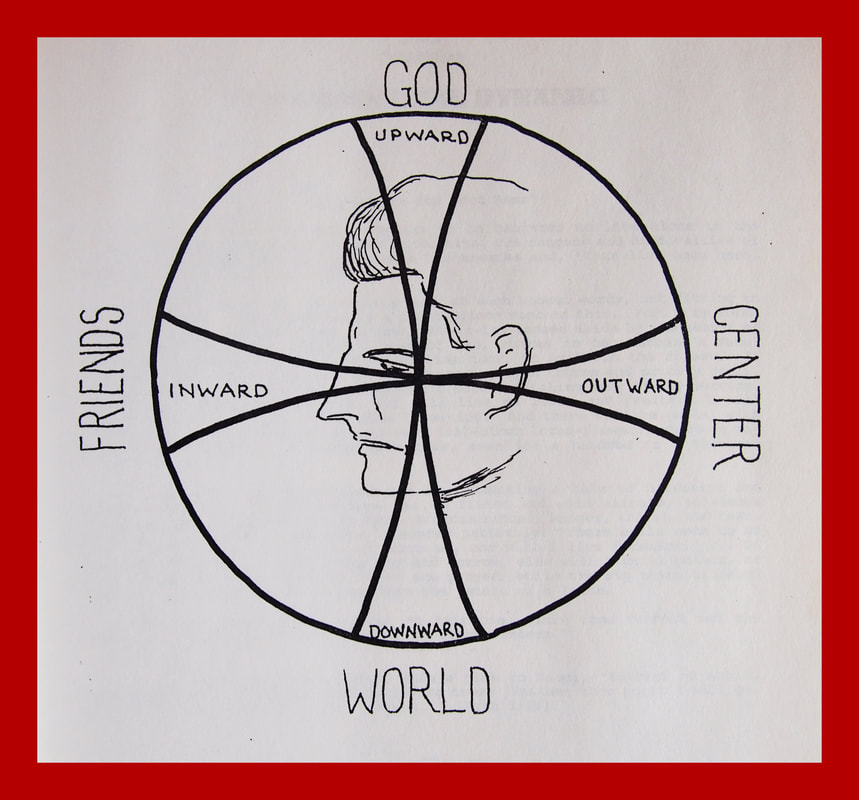

Our lives are lived in a milieu of influences which we perceive as distinct and discrete. From time to time we may concentrate on one or another of these areas, but most of the time we glide along paying little attention to these influences. When there is a crisis we are jolted out of our complacency and become concerned about some aspect of our existence we otherwise blithely ignore. A fellow was sitting in a dental chair gripping the arm rests so tightly that his knuckles were white. The dentist paused and tried to reassure him. “Don’t worry. Try to relax.” “I’m not worried,” the patient responded, “just incredibly alert!” There are times when we pay close attention to our physical well being. There are other times we let that slide and our whole lives may be tied up in religion, or some creative endeavor, or a matter of romance. A religious experience might draw our attention to a new dynamic taking place between us and the transcendental sphere in our life, just as a love affair will pull us out of our relaxed mode into excitement about our social sphere we had just recently been taking for granted. Our friend is an alcoholic. He is a binge drinker. He can go for a period of time without getting drunk, but one day he will take another drink and he will be helpless. He will drink himself into a stupor and as often as not he will simply pass out wherever he is, at a bus stop, on a sidewalk, in a friend’s house, under the table in a restaurant. If he is with friends they will take care of him. If he is alone, he is alone. At least seven times his cell phones and money have been stolen while he was unconscious in some public place late at night. Why doesn’t he take care of himself? The answer may not be far away. He is gay, his sister is a prostitute, his mother is a widow in an ethnic minority village that specializes in drug traffic. It would be hard to find a person who has had sex with more men in more circumstances in the same span of time as our friend. He is a genius at it, an artist, but not a connoisseur. His tastes are eclectic and varied on many subjects. He has intelligence, wit, compassion and loyalty. But he is tasteless in his choice of self-indulgences and modes of self-destruction. I have spent time concentrating on our friend and it has helped me clarify a great deal about our physical reality, its vulnerability and survival. My description, however, would probably not be enough for you to be enlightened by him. Someone else, though, might be a victim you come across who calls forth your deepest level of humanity. It is very common for persons to gain their truest insight into the whole world of nature through the agency of some person who becomes its symbol for them. We do not usually find the metaphors that inform us about life’s urgency and reality, those metaphors find us. In the same way, the transcendental realm of reality will be represented to some of us most vividly by experiences we have had with Mary, or Jesus, or the Buddha, or Rama, or Brahma, or a spirit we encountered in the forest or on a mountaintop. And yet many of us have had no such experience and just have to rely on the testimony of others for the time being. Most people at more than one point in their lives relate to somebody in such a way that they are transformed by the relationship into beings entirely better than they were before. Lovers tend to do that for us. Being in love with someone is the best way to discover the validity and the power of the whole societal sphere of our spiritual environment. The inner center of our minds, where our unconscious minds retain images, information, and identities waiting for us to discover, sometimes urgently imposing on us to fathom them, is a spiritual area that is also separate from our daily consciousness to such an extent that it seems “other” to us, a different spiritual sphere. The silent center is like a different person, at first. It is the well-spring of creativity, although it is a preserve of silence and the absence of confusion. It is the one place a person can be truly silent, completely vulnerable, and absolutely honest. Everywhere else a person is acting or listening. In the silent center, at the heart of a person, life’s priorities are clearer, integrity is obvious; one’s very identity is revealed. Spirituality is a topic of widespread interest these days. It has replaced religion as an operative dynamic for some. Spirituality has attained academic status as a valid topic for advanced study. I have been working on this for nearly sixty years. One conclusion I have made is that spirituality ought to be more comprehensive than are most discussions of it. Our perception of reality needs to be inclusive. We learn who we are, how we function and grow, and what the rationale behind our existence and trajectory is by being aware of four spheres of influence. They are the transcendental sphere above us; the sphere of our physicality and of the realm of nature which upholds us as our foundation; the societal sphere whose reality is exposed to us most distinctly through our relationship to significant others whom we love unconditionally; and the inner sphere which we discover to be a creative silent center in the midst of our unconscious. There was once a little man called Niggle, who had a long journey to make. He did not want to go, indeed the whole idea was distasteful to him; but he could not get out of it. Niggle was a painter. There was one picture in particular which bothered him. It had begun with a leaf caught in the wind, and it became a tree; and the tree grew. Soon the canvas became so large that he had to get a ladder. “At any rate, I shall get this one picture done, my real picture, before I have to go on that wretched journey,” he used to say. Yet he was beginning to see that he could not put off his start indefinitely. The picture would have to stop just growing and get finished. There was a knock on the door. “Come in!” he said sharply and climbed down the ladder. It was his neighbour, Parish; his only real neighbour, all other folk living a good way off. “My wife has been ill for some days, and I am getting worried,” said Parish. “And the wind has blown half the tiles off my roof, and water is pouring into the bedroom. I think I ought to get the doctor. I had rather hoped you might have been able to spare the time to go for the doctor, seeing how I’m placed.” “Of course,” said Niggle; “I could go. I’ll go, if you are really worried.” “I am worried, very worried. I wish I was not lame,” said Parish. So Niggle went. It was wet and windy, and daylight was waning. The doctor did not set out as promptly as Niggle had done. He arrived next day, which was quite convenient for him, as by that time there were two patients to deal with, in neighboring houses. At that moment another man came in: tall, dressed in black. “Come along!” he said. “I am the Driver. You start today on your journey, you know.” [Niggle fell asleep and overheard two Voices debating his fate.] “Still, there is this last report,” said the Second Voice, “that wet bicycle-ride. I rather lay stress on that. It seems plain that this was a genuine sacrifice: Niggle guessed that he was throwing away his last chance with his picture.” Niggle thought that he had never heard anything so generous as that Voice. “I think it is a case for a little gentle treatment now,” said the Second Voice. It made Gentle Treatment sound like a load of rich gifts, and the summons to a King’s feast. They came at last to a place where a great green shadow came between him and the sun. Before him stood the Tree, his Tree, finished. All the leaves he had ever laboured at were there, as he had imagined them rather than as he had made them. “Of course!” he said. “What I need is Parish. I need help and advice: I ought to have got it sooner.” [Tolkein] In Tolkein’s little story, cut all the shorter in this version, are all the spiritual dimensions. Niggle’s identity is defined by his own creativity as a painter, a painter of leaves. The inspiration springs from deep within. He is defined as well by his compassion for those in need, and by his relationship with Parish, who is his only friend. Symbolically, Niggle has to come down from his ladder to help Parish, a cripple, and his ailing wife. This eventuates in Niggle himself becoming like them, sick … hastening the day when “the Driver” comes for him. Strangely, it is this selfless act that accomplishes what Niggle was never finishing on his own: the painting, and a true bond of intimacy with Parish. All this was done, as it were off-stage, but Niggle does overhear two supernatural voices evaluating his life. The Second Voice who decreed “Gentle Treatment” for Niggle, was the representative of the Transcendental dimension for Niggle. From a spiritual point of view we are conscious of being in a condition where four different types of spiritual forces overlap: the transcendental, the physical, the societal, and the unconscious. What is your spirituality? Your comprehensive reality Your potentiality – what you would be if your potential were fully realized A conception of the dynamics of who you are with aspects of you growing A description of what happens when aspects of you become so dysfunctional that all aspects of you are caught into dysfunctionality and deterioration ____________________ Tolkein, J.R.R. 1964, from “Leaf by Niggle” in Tree and Leaf. London: Unwin Books. [Essay 1: SPIRITUALITY. This is the first essay in a series on spirituality.] |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed