|

The debate about Christians using Jewish worship forms, such as the Seder service, emerges every year during Lent. It is part of the wider, on-going argument about the validity of Messianic Judaism and Hebrew Christian churches. In general, conservative and orthodox Jews are adamant that the intrusion of Christians into Judaism is to be opposed, and conservative evangelicals also view efforts to appropriate Jewish rituals and festivals as “efforts to undermine the separation of the two religions.” Evangelicals do not want to understand Jews, they want to convert them. Jews argue that the one thing settled between Jews and Christians is that they are permanently separated by the difference of opinion about Jesus as the same Messiah the Jews anticipated and still expect.

Rabbi David Wolpe put it this way: “There are some today who speak of themselves as ‘Jews for Jesus.’ This is nonsense. It makes as much sense as saying ‘Christians for Mohammed.’ A Jew who accepts Jesus has cut himself off from the faith community of Jews, and that has been so for 2,000 years. Moreover, that Christians argue with the Jewish community about the legitimacy of ‘Jews for Jesus’ is presumption of a high order. I would not presume to tell Christians who is a Christian and emphatically reject the idea that the Christian community can tell me who qualifies as a Jew.” [Rabbi David Wolpe, “Why Jews Don’t Accept Jesus” January 9, 2003 reprinted in the March 27, 2021 edition of Jewish Journal.] At the heart of Rabbi Wolpe’s reasoning is the fact that the world is a mess. The job of the Messiah is to fix that. Jesus did not do that. Ergo, Jesus is not the Messiah. It would be best to separate the matters into two parts. MESSIANIC CONGREGATIONS My own limited experience has convinced me that the effort to incorporate Messianic theology into Jewish traditions is much older than “Jews for Jesus” which began in the 1970s. In 1960 I was hired for the summer to work as a counselor at Presbyterian Camps in Saugatuck Michigan. There were 3 camps on the campsite owned by the Presbytery of Chicago. One of them was Camp Piniel operated by the First Hebrew Christian Church of Chicago, which was an outgrowth of Piniel Center, a neighborhood house established by Presbyterians more than a century ago. As I remember it being explained to me, the congregation was Jewish who believed Jesus was the promised Messiah. They continued Jewish worship in the Ashkenazi (European diaspora) form but included readings from the New Testament. It was significant that this congregation was a full-fledged member of Chicago Presbytery. They were somehow Jewish and Presbyterian. It was founded in 1934. In 1960 I heard that it still conducted some services in Hungarian language. Daniel Juster, pastor (rabbi) of the First Hebrew Christian church of Chicago from 1972-77, was a graduate from my own alma-mater, McCormick Theological Seminary, and was ordained as a Presbyterian teaching elder. The church is now named Adat Hatikvah Messianic Synagogue and is in the Chicago suburb of Deerfield. It is no longer listed as a church of Chicago Presbytery. Notice, the congregation no longer calls itself either Hebrew or Christian. I do not expect the aggravation to go away that is felt by Jews against invasion and aggression of Christians, nor do I imagine the anguish felt by Christians, who love their Jewish heritage and want to retain as much as possible of it, to diminish in the face of denunciation for embracing Jesus as Messiah. But I will argue that it is not up to Jews to invalidate the Messianic movement. The heart of the matter is that it is basically legitimate for a new religious movement to attempt to establish itself as a form of an older one, even if the older religion doesn’t like it. Christians hated it when Joseph Smith announced the formation of The Church of Jesus Christ, Latter Day Saints (LDS or Mormons, for short). “They are not CHRISTIAN,” the Christians ranted. It was not, however, up to the Christians to decide what the Mormons called themselves or what they borrowed from Christian jargon and practices. Christianity was at the core of Mormons’ theology and identity. By the same token it is not up to other Christians in the Philippines to decide that Iglesia Ni Cristo is not Christian. Amalgamated religious movements have a right to exist in a free society. Here in Chiang Mai there are Jewish-Buddhists (espoused by several people from New York City) and a prominent Baha’i community (most of whom were refugees from Iran). No matter what religious leaders think of it, Baha’i is firmly convinced that it is composed of the most shining tenets of each of the world’s great religions (amalgamated, indeed!). One of the most impressive Baha’i temples is in Tel Aviv and the other is in Winnetka just north of Chicago. Indeed, the entire history of religion is full of movements that incorporate older traditions, as well as movements to eliminate and purify religions from those old traditions. SEDER SERVICES Christian Seder services are a separate matter. In the last few decades many Christian churches have conducted Seder services using Jewish rubrics. Individual families or groups have done so as well, including the Obama family in 2009 (pictured above in a White House photo of the first such service in the White House). They usually try to re-enact the traditional Seder service while mentioning the way it might have happened with Jesus and his disciples on the night before he was crucified. Actually, the form being used today originated in the rabbinic period after Jews and Christians had separated. Any connection between what Jesus did that night and what Jews do in Seder services is largely speculative. As for borrowing cultural bits to incorporate into Christian worship, that is always controversial. Here in Thailand the most conservative cultural preservationists do not like it when Christians use Thai traditional dance or music, and conservative Christians also refuse to do so. But most Christian churches now set up shrines to “honor” royalty on their birthdays or memorial days. The prescribed ritual is decidedly not Christian. Royalty are venerated because they are avatars of the Hindu god, Rama. In various ways Christianity is continually borrowing from other religions. In the USA the use of African-American spirituals has passed into acceptability. Under certain circumstances it might work to have a Hopi dance group do the Butterfly Dance in a Christian event, but we have come to understand it is wrong to have the dance and costumes done by those who are not Hopi ethnic Native Americans. Many churches could as easily do a Taize chant as to have a bagpiper lead a procession, but they would draw the line at having a Buddhist monk pronounce a benediction or a Muslim start a Christian event with an invocation (as the Presbyterian General Assembly did in 2016, creating a furor). It is correct these days to yield to those of a given religious and cultural tradition if they object to others outside that religious-cultural tradition using its forms or artifacts. So, it is taken for granted that Jews should have the deciding voice about whether Christians should be allowed to borrow any form of the Seder service for Holy Week. Nevertheless, that proprietary right has its limits. That limit has been reached when the form being questioned is basic to the very character of the group being challenged. That is why I would say that Jews should be listened to carefully when they criticize a Presbyterian Church for desecrating the holy Seder service if it is being conducted on Maundy Thursday. But Jews would be off base if they try to prevent the Adat Hatikvah congregation from doing so.

2 Comments

Images of Gay Muslim Reality in South Thailand

Samak Kosem has undertaken a daunting endeavor: to artistically portray the reality of Islamic LGBTK life in Thailand’s far south. He is (among other things) an anthropologist and a graphic artist using photography, videos, and montages to elicit insights. In the process of composing his projects he investigated and interviewed communities to confirm his perceptions that LGBTK people of all ages are living throughout Muslim communities but that conversation about gender must be nuanced and indirect. In a “Payap Presents” program from Payap University on March 24, 2021, the Chiang Mai University PhD candidate told us about several of his art projects and the metaphorical theory behind his productions. One set of images was of sheep, which he explained are the most marginalized animals living in Islamic villages, as are gay people; but in his exhibits he let the pictures speak for themselves saying, “This is what marginalization looks like.” From photographs, Samak proceeded to sculptures of sheep to require visitors to go among the sheep. Another project was a video of an actor on a crowded holiday beach surrounded by Muslim families. He was apparently celebrating life as a gender-ambiguous pondan or kathoey. In explaining to others on the beach what he was doing he had obfuscated; he told them the video being made was about littering. The video also said, “This is what it ought to be like being gay in the middle of everyone.” A third project was portraits of gender-diverse Muslims of various ages, but he had hidden their eyes behind blocks of text to protect their identities because fundamentalist groups used such pictures to find the individuals and intimidate them. Reality is dangerous. Samak described some of his conclusions and inferred others. The overall impression he made is that being a gay Muslim in South Thailand is publically unacceptable. But, as everywhere, there are gay young people. They are being confronted and tolerated (within limits). In one school pondan boys are segregated for daily prayers, “to protect them from bullies,” the teachers said. This is progress beyond the bullying being encouraged or ignored. Mothers, Samak found, are more tolerant of gay boys because they realize some of their sons are gay, but men are more rigid. Samak concluded, “You can be queer and you can be Muslim. But that cannot overlap.” For example, if a “Tom” (lesbian presenting as male) is participating in something religious, they must wear a hijab (Muslim headscarf). Gay men are pressured to get married by age 40 and from then on they conform to religious moral norms again. Samak has made presentations to Muslim audiences in which he interpreted his art. He characterized some of his audience as “shocked.” It seems that religion has a stifling influence on trends toward social acceptance of Thai LGBTK Muslims. It is behind Thai society at large in this regard. However, progress is being made in small ways wherein religion is not the overwhelming factor. I was impressed that in the Muslim south just as in the Buddhist north, “If your family accepts you, you are fine. But if your family does not accept you, you have nowhere to go.” In Thailand all progress toward gender equality starts with the family. Thank you, Samak Kosem for a fascinating presentation and best wishes as you complete your PhD at Chiang Mai University. To see more of Samak’s work, access: http://aura-asia-art-project.com/en/artists/samak-kosem-minorities-and-artwork-in-islamic-society REFLECTIONS ABOUT TEACHING ENGLISH IN THAILAND

Twenty years ago Dr. Janjira Wongkhomthong and I undertook an innovative venture, to transform Christian University of Thailand (CUT) into the English language hub of the western exurbia of Bangkok. It is fairer to say she directed the exploration and I was her scout. The objective was to have CUT come to mind when people in our part of the country thought of English language. As I reminisce, what we tried from 2001-2007 was both audacious and intriguing. There were lessons to be learned from our attempts, mostly about intractable obstacles that block educational innovation and English language enhancement in Thailand. First a list of things we tried: 1. “English activities workshops for teachers” (7+ workshops) 2. “English camps” (5 week-long camps and several one day fun events) 3. “English for Professional Nurses” (10 workshops) 4. “English for RATGEN” (The Ratchaburi Electric Generating Company) (4 modules) 5. “English for the Ministry of Culture headquarters staff” (3 modules) 6. “English for staff of Nakhon Pathom District” (one attempt) 7. “English for staff of the Governor’s Office of Nakhom Pathom” (one module) 8. Required English proficiency for all degree programs of CUT’ 9. Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language 10. “English In A Minute” (4 series of tapes for local radio stations) 11. “English for Advanced Professional Nurses” (specialized course in the curriculum) 12. English contests for high school students 13. Preparation for passing the government English exams These endeavors were of three types: (1) to establish the CUT “brand” as a reliable and available resource and top-notch center for English programs; (2) to meet expressed need for special English training in workplaces; (3) to explore research and development plans for meeting the country’s need for better English competency. In retrospect we learned more about what we ought to be doing than what people wanted us to do. Our discoveries were potentially more valuable for establishing administrative priorities than educational plans. English is not a top priority. It is important to keep this in mind. All attempts to teach English confront the fact that something else is more important. English acquisition is not unimportant, but there are always over-riding reasons for students and clients to sign up for a course or event. English is supplemental. Our efforts were most successful when we aimed to satisfy the main objectives. English teachers liked our workshops if they were fun, if they provided ideas for things to do with children that didn’t need a lot of preparation, and if the workshop filled some in-service requirement for the teachers. The workshops for nurses were a hit as long as we focused on successful communication with patients, and that involved basic principles of communication with people of different cultures. Profit should not be an objective. Aside from full-fledged academic courses, one-time short courses and workshops are not highly profitable. The reason for providing the workshops and events should be to publicize the institution, to expose the workshop leaders to workplace realities, and to show support for community concerns. An effective language workshop must have an effective student-teacher ratio which will always be smaller than a student can afford, so supplemental finances are always going to be needed either by reducing the cost of the workshop (meaning the university assumes some of the cost) or by attaching the workshop to a program that is funded otherwise (which usually involves increasing the number of participants and reducing the learning outcomes). Special English takes R&D. By the end of our 7 years we had learned that there is no short-cut in the research and development of helpful courses for specialized workers, but there are ways to be more effective. Every workplace in Thailand has its own limited need for using English. It is best to get clear about what the participants need to be able to communicate in English before (or at the beginning of) a workshop. If the need is for staff to take international visitors on a tour of a factory the conversation is different from negotiating a contract for equipment. Our most successful short courses were those where the communication need was clearest and we had time to refine the course. Proficiency takes time. There is a continual stream of programs that promise you can learn a language in no time. Those are unscrupulous. On average it takes 200 hours of educational effort to improve one level in English proficiency, from early intermediate to intermediate, for example. For this reason, “achievement” is often substituted for “proficiency” as a program objective. It is too disheartening to come right out with the truth that a 20-hour workshop can’t get you very far toward proficiency. Thailand is getting better. It is undeniable that it is easier to get around the country using only English than it used to be. Far more people have functional levels of communication. But at the same time graduating students in Thailand have slipped below those of neighboring countries to such an extent that the educational effort in Thailand is widely agreed to be failing. One explanation for this paradox is that the prescribed English curricula are wrong, and so students are not motivated to do more than pass the necessary exams, but they learn to get by with English in many other ways. That, too, was one of the things we learned between 2001 and 2007, but we did not find out what to do about it. Policy decisions are not in the hands of English teachers. The head of a Bible College was disgusted at a picture he saw of me participating in a service for a Buddhist abbot in our neighborhood. He thought it represented a repudiation of Christianity.

Here in “The Land of Smiles” being soft on Buddhism is one of the things that can disqualify you from the ranks of trustworthy Christians. Being openly LGBTK will relegate you to the back pews as well. One cannot be both highly political and a prominent Christian leader. Those three: that’s about it. Interestingly, having a position on abortion doesn’t wave a red flag. Nor does your conviction about how many days it took God to create the world in which we live. I take this as evidence that the tests of unworthiness are not the same for Christian groups everywhere. Most of the things which are fracturing Christianity in the USA are fairly inert here. Conspiracy theories in the USA about the causes of wildfires, climate change, or the current pandemic have caused people to leave churches and pastors to resign. But not one case of anything like that has leaked into this country. Obviously, the corrosive factors that disintegrate religious unity are cultural. If they were religious or theological they would be cross-cultural. Several years ago the Protestant church in Thailand quaked and some fractures occurred. At the time, I had our class of Master of Divinity students study the cause of these splits. They did interviews and gathered histories. In every case the presenting reason for the impending split was theological having to do with the “power of the Holy Spirit” or the inerrant truth about some aspect of religious practice. But the division in every case was on social lines, one clan versus another, or unwillingness to share power or to tolerate dissent. The struggles became so widespread that the national church conducted a series of gatherings to disseminate the “truth about the Holy Spirit” and quench charismatic zeal. None of the churches reconciled through that campaign although restored calm convinced a couple to remain in the denomination. Our class concluded that since the cause was social-cultural, a theological appeal would not get at the root. In counseling we know that the presenting issue is rarely the basic issue. “His drinking” may get a couple to a counselor, but the counseling must delve deeper if the marriage is to be saved. You cannot heal a social division by simply addressing the presenting issue any more than you can heal a disease by suppressing the symptoms. Some very recent surveys suggest that almost half the Protestant pastors in the USA have heard QAnon conspiracy theories mentioned by members of their congregations. In many cases these have led to serious concern about the future of the American church. I read an article just a day ago that worries a QAnon religion (sect or cult) is emerging. At the same time voices are reminding us that the situation in the USA is cultural division which cannot be overcome by appeals for either national unity or religious reform. The problem is that conspiracy-driven evangelicalism is anti-intellectual, and therefore impervious to fact-driven intellectual arguments. Perhaps viral infection is an analogy. A virus is hard to kill without killing the host it has infected. If the victim does not mobilize anti-viral responses the victim will die. A vaccination works to alert the host to the possibility of infection so that the antivirus is already available when the virus shows up. The body must mount the attack and heal itself. Since churches and religious organizations are aspects of the cultural body-politic, the protection and preservation of those institutions is not all that’s at stake. The whole body is infected, not just the organs of religion. Well, I began this exercise by reflecting on how different Christian intolerance in Thailand is compared to the USA. Having come this far, I have one final observation. Christianity in Thailand used to be far more intolerant of Buddhism than it now is. Living together has made a difference, but working on shared concerns has tipped the balance. Justice and compassion are “enzymes” religious organs produce for the whole body. The HIV-AIDS crisis as well as several previous ones (leprosy comes to mind) stimulated inter-religious action that helped religious intolerance and rivalry fade. COVID could be America’s vaccine to get the body-politic alert to the anti-intellectual virus that’s attacking. If religious organs pump out quantities of justice and compassion they will have done what they can. REMINISCENCE

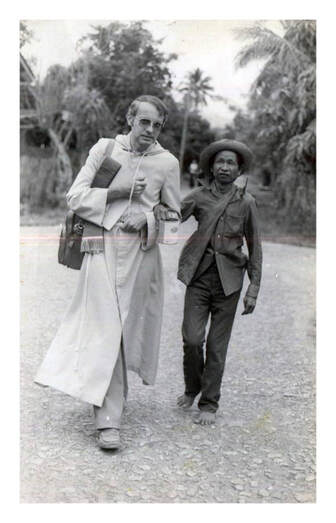

From the first year I became a teacher in the theological seminary here in Thailand in 1965 I began to realize, “We are not doing this right.” Then 40 years ago I had an opportunity to try a new approach to theological education. For a couple of years I took a group of students on week-ends to work in a cluster of village churches. The work was practical and involved teaching classes, leading worship, preaching, and sometimes interventions. Every week we’d then discuss and reflect on what had happened. What we did was reverse the educational paradigm for those “practical theology” functions (i.e. preaching, teaching, counseling, and officiating). In traditional classes the process is essentially to focus on a concept and then tell stories about how that works out in various situations. We gather in classrooms to study activities going on somewhere else. It is about principles in search of applications. On our weekends the situations came first and the concepts were identified in retrospect. It was inductive. We did what we needed to do; then we thought carefully about it, and tried to do it better the next time, if there was a next time. We were constantly surprised by peak learning moments. The best were challenges or interruptions, random and unplanned. Sometimes it was a spontaneous act that reverberated most resoundingly. [I was astonished by the ripples that resulted from my simply taking a blind man to breakfast one Sunday morning (as in the picture with this essay). Most of the student-team hadn’t realized how important random acts of kindness could be as keys to ministry.] Context was a continuous issue, without which most of the learning experiences made less sense. In fact, it was context that made every incident unique, and it was uniqueness that demanded coherent explanation, that being the threshold of theological meaning inherent in the experience. Pretty soon it happened that the learning that was taking place not only informed us about the practical undertakings in which we were involved, they were also leading to vocational and spiritual discernment that just never happened as predictably in other kinds of theological education. Another result was the evolution of community. At the outset we were a group of outsiders who came on weekends. But our group coalesced and became colleagues. The villages to which we went welcomed us as they were able, but that evolved to the point that we actually became part of the village to some extent because of how we slept on floors and ate in the market or in church halls with kids. If there was a village fair we were there, and toward the end of the year we had a fair and the whole village came. If we had not had to conform to the university’s academic requirements and calendar we would have achieved a level of involvement in which we became participants in village affairs with voices in creating the village’s future as well as expanding the capacity of the church to be effective and influential. That was a vision some of those students perceived. Even though that model was not continued by the seminary in Thailand, some of those students never lost the vision. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed