|

It looks like progress is being made in Thailand against COVID-19 any way you figure it.

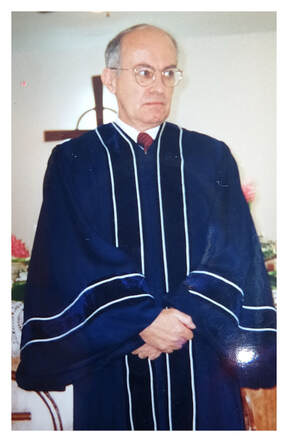

As of Sunday, September 26, there are 122,463 patients receiving treatment. The average per day for the first 5 days of the month was 159,528, and the average per day for September 22-26 was 126,367. That means that there are 33,161 fewer patients being treated than at the beginning of the month. New cases are down from 15,161 per day September 1-5 compared to 12,307 lately, a reduction of 2854 new cases per day. Vaccination surely is having an effect. As of Sunday 50,101,055 vaccinations have been administered. The Prime Minister’s office reports that 44.45% of the population has had first shots, 23.9% have had two shots, and booster shots are beginning. School-age children will begin receiving vaccinations very soon (maybe this coming week). Friday, September 24 was Prince Mahidol Day, a national holiday in Thailand. The Prince was the father of the late King Bumiphol, and the grandfather of the present King. Prince Mahidol is heralded as “The Father of Modern Medicine and Public Health.” To mark the holiday a mass COVID vaccination campaign was held with a goal of 1 million doses. That target was exceeded. 1.44 million doses were dispensed. That number included 947,290 first doses, 320,864 second doses, and around 172 thousand booster (3rd) doses – Pramote was one who got a 3rd jab on that day (picture attached). Despite some stumbles along the way, the Prime Minister says it looks like the country will be able to achieve its target of having 50 million (70+%) of the population (or of “targeted groups”) fully vaccinated by the end of the year. The government has “procured” 125 million doses to accomplish that. That has naturally encouraged talk of re-opening the borders to tourists and retirees. Grand plans are being announced in these regards. Meanwhile, the vaccination rate in 5 tourist-target provinces, including Chiang Mai, has not been sufficient to permit open-doors to tourists on October 1. The new opening date is now November. Since the beginning of this major outbreak announcements of plans for getting businesses back to work have been followed by decisions to postpone whatever was planned. In a few cases the plans went forward and results were unfortunate. Aside from the government, reports on how things have been going have come from two types of sources. Both have built-in biases. Commercial sources paint rosy pictures of excellent business opportunities and reports of promised start-ups. Individual articles about things like a new up-scale restaurant inside the re-purposed hull of an airplane tend to hide the fact that there are still no customers. The other source tries to sustain the view that the country is teetering on the brink of political chaos caused by the government’s failure to respond in any way to the pandemic – no help of consequence has come for countless survivors whose financial providers have died, vaccine is being shunted toward the affluent, and so forth. It is undeniable that there is hardly any cushion if something goes wrong between now and New Year’s Day. The economy must begin to take off. People need jobs. Children need to get back into classrooms. The Prime Minister needs to be right. Or else.

0 Comments

It is pious heresy that “belief is the ultimate achievement and final goal of faith.”

It is invalid to use “belief” as a test of faith. We do that when we limit the inquiry into a person’s suitability for church membership to the question, “Do you believe that Jesus Christ is your Lord and Savior?” A variation of that, and that’s all it is, is the question, “Are you saved?” Such questions imply that faith is cognitive. It’s something to be thought. Even institutions (in this case churches) that accept people from birth require them to think about it and come to an appropriate, overarching conclusion. This is actually important only for institutional maintenance. It filters out potential members who will prove disloyal or uncooperative. But the test does not work even to do that. No member, not even one installed into leadership, relinquishes the right to dissent. Unconditional assent is not a legitimate requirement if institutions and the people who compose them are functionally organic. And we are organic. We change as we grow, even if the change is toward decay or decadence. Institutions change. Change is constant. Therefore, the expectation of unyielding agreement is absurd. But that is exactly what is meant when belief is the measure of a person’s soul and spirit. Nor are institutions consistent about it. The same organizations that insist “human life begins at the moment of conception” and “abortion at any time is murder” also insist that the essential proof of human worth is consciousness of salvation. The moment of cognition is the one that counts. It is impossible to have it both ways, squirm as you may about the details. Even “Holy Mother Church” has fallen short, and sometimes admitted it, although the confessions were tardy, abbreviated, and did nothing to amend anything for those abused. I digress. The idea, of course, is that proper belief leads to proper actions and attitudes. Pure belief purifies a person’s thought, word and deed. So there is no need to ask about a person’s actions when questioning them about their belief. A person’s belief may not be “all there is to it” but belief is sufficient to test since it must lead to action. In retrospect, in celebrating memories for example, actions and accomplishments are mentioned prominently as if they signify the value and identity of the person and proof of their belief which indicates how worthy they are to be honored and certified for rewards temporal and eternal. If this concept works as it should, there can be no exceptions. But there are exceptions. In fact, there are exceptions without exception. There is no case in which a mortal human being can be held to be blameless throughout life in thought, word and deed. No, not one. Actually, it is belief in the trustworthiness of belief that is faulty. We have thousands of proofs that belief is not final. For example, there are vaccine resisters who are letting their belief about the vaccine dominate their actions and often even their actions against people who believe otherwise. But some of them, having refused vaccine, masks, and social restrictions, get sick with COVID. Deathbed confessions that “I wish I’d been vaccinated” are heart-rending. But their window of opportunity for believing is over. There is a window of opportunity to believe; beyond that it no longer matters whether you believe or not. What is it, then, that is ultimate if belief is penultimate? It is action, but not our action as individuals. Concerted, compassionate, action by communities is of greater consequence than individual efforts. That is obvious. And it is the best that we can do. At its best it is noble and influential. But even that is not ultimate. The measure of what is ultimately important resides outside history and is integrated within dimensions beyond human admittance. We cannot speak of it. In matters of ultimate belief we can only confess our limitations and profess hope. We cannot know that which cannot be known. We can only move forward as if our belief is sufficient. The god of whom we can speak is too small to be God (to use JB Phillips’s venerable phrase). Theological language is all liturgical, it is language of worship. Religious belief, then, is something worshipful we do as we pay attention to things we can see that need our attention. Effective belief depends on discernment about what is demanding our attention. Eyesight and brainpower are not enough. The best indicator of authentic discernment is a radical change of heart and perspective towards compassion for the most abused and unfortunate. Belief that matters is what we believe about who we are in the world. That is what informs us. Hope and reverence are what inspire us to care. “Nothing makes us believe more than fear, the certainty of being threatened. When we feel like victims, all our actions and beliefs are legitimised, however questionable they may be. Our opponents, or simply our neighbours, stop sharing common ground with us and become our enemies. We stop being aggressors and become defenders. The envy, greed or resentment that motivates us becomes sanctified, because we tell ourselves we’re acting in self-defence. Evil, menace, those are always the preserve of the other. The first step towards believing passionately is fear. Fear of losing our identity, our life, our status or our beliefs. Fear is the gunpowder and hatred is the fuse. Dogma, the final ingredient, is only a lighted match.”

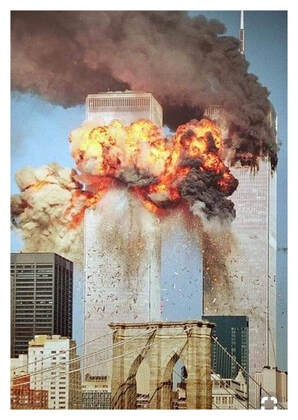

-- Zafon, Carlos Ruiz, 2010. The Angel’s Game (English trans.), Phoenix, p. 247 A very ambiguous “angel” (or perhaps a psychotic fantasy) visits an exploited Spanish writer with a commission. The writer is to write a novel that presumably will serve as a substitute holy scripture for a new generation. Ominous as this turns out to be, the “angel” tells the author the rationale that is to be used: When we feel like victims, all our actions and beliefs are legitimised … we become defenders. …The first step towards believing passionately is fear. That passage arrested me. “That,” I thought, reaching for my pen, “is profound.” What made it profound, in my mind, among the myriad of profundities laid before us in this time of unprecedented availability of literature and wisdom, is how it capsulizes the motivations of so many of our responses to threats. Or at least some of the motivations. But, having reflected on the terrorist attack on the World Trade center these past few days, and thereby brooding about “America”, on September 11, 2001, I think the “angel” was over-simplifying the range of human reactions. On 9/11 anger, victimization, and alienation were NOT the first responses. At least we have chosen stories of heroism, gallant sacrifice, and patriotism to be remembered. Some of those stories are on their way to becoming legends. But those stories also refer to fear. The account of half a million people being moved by boats from Manhattan to New Jersey by heroic sailors operating ferry boats and pleasure craft, “the largest marine evacuation in history,” is also about 500,000 people trying to escape. The images of 9/11 are not of only brave fire-fighters going into smoking and blazing towers but of people running for their lives. It’s complicated. But has the “angel” got it right, that the root of belief is fear? It is possible to see the US government’s responses pretty much as the “angel” described them. “We were attacked. So we retaliated.” In fact, what was released at that time was more extensive and intense. We learned in one terrible morning that the USA is vulnerable after all. That led to: “This is not to be stood for. America needs to defend itself. The world is undependable. We need leaders who will restore us. We need to be able to defend ourselves … we need guns … we need to proud and keep out illegal, undesirable, and unnecessary foreign elements”. Those attitudes blossomed and spread. Zafón was describing Spain, especially his native Barcelona, after the Spanish Civil War and during the dictatorship of Franco. He is also narrating the legitimization of terror and revenge in his novels. It is state terror, but it plays out in particular incidents with indistinct chains of cause. Zafón “divides his time between Barcelona and Los Angeles,” the dust jacket of his book tells us. He knows that the “angel” was enunciating a universal truth. It applies to Croatia, China, Cambodia, and Cuba and it threatens unity and cooperation whenever it takes hold. Does legitimate religion adequately counter this fear? Christian theology struggles as it tries to say it does. In some way even God is to be feared. Fear is basic. Some kind of fear is fine. Buddhism is a search for serenity in eternal uncertainty and change. Some religions try appeasement … some through unspeakable sacrifices and others through metaphorical ones. Without fear that whole apparatus (some say “all religion”) would be unnecessary. So, religion does counter fear although some strategies are paradoxical. Sadly, religion as we have it these days, does not always serve to keep fear from being transformed into defensiveness, too often manifested as counter-terror, and soon enough into a belief system. The writer in Zafon’s novel comes to believe that the “Angel’s game” was to scare the writer into writing about fear as the seed of belief so as to make it happen. It remains unclear at the novel’s end whether that would have worked on a universal scale, or whether the “angel” was only working on the writer. If fear is the impetus for a protectionist belief system that legitimizes violent opposition and the consequences that come from that, love and compassion are the other alternative. Love and compassion are only sustainable, however, when we are not scared to death. We can only be loving and compassionate when we are not overwhelmed by fear. Zafón knows, and we know, that some religion has surrendered to angels’ temptations to fight terror with terror. The question we need to answer before it’s too late for us is whether there is a better way that actually works. I think the “angel” was right that if we feel threatened fear will abduct our belief system. Unless we feel protected, really taken care of despite everything, we are vulnerable to a system that turns us against our neighbor and renders us hopelessly lonely. [Credit the New York Times, for the picture accompanying this essay.] “The first thing that happens once you have been accused of breaking a social code … The phone stops ringing. People stop talking to you. You become toxic.” “Here is the second thing that happens, closely related to the first: Even if you have not been suspended, punished, or found guilty of anything, you cannot function in your profession.”

How true. Back 20 years ago this is how my pastoral career ended. I was accused of breaking the social code that required me to demonstrate my cis-orientation. I was given the choice of dismissing Pramote (my same-sex spouse) and living un-controversially, or finding my way outside the church. I decided to see who would continue to contact me. The phone stopped ringing. Then I was warned not to try to re-activate my pastoral credentials but to just stay off the rolls of any pastoral or missionary list. That was clarified, “Stop doing anything as a clergyman.” I was to hang up my robe and find another job. I reckoned it did not matter in terms of my ability to function as I had been, conducting spiritual life retreats, writing Bible studies, and teaching in seminaries. However, my ability to do those things was never counted when the time came to let me continue or let me lapse. I was never given a chance to appear and discuss this at all. Discussions about me were held without me. It was no longer my abilities that mattered, but my social misconduct. Upon further reflection I think it is unclear that my knowledge, skill, and “call” were ever as important to my functioning as a pastor as was my social position. I seriously underestimated that all along. I was valuable to congregations and communities because of my being the pastor. In those days (the 1960s to 80s) pastors were still valuable to congregations and communities as members of the leadership who oversaw the best interests of the people, who were leaders with various perspectives and privileged entre into private lives at critical times, and due to their collective memory. Formerly, pastors were key members of that leadership, but that was changing in the 1980s. By that time a pastor had to earn esteem. It no longer came with the title. Longevity was important, but so was a track record. Every pastor developed their own persona and standing. But it only seemed to have much to do with how good they were at their jobs as preachers or evangelists (recruiters of members), or even as chaplains to the community. Beneath it all there was a consensus about what a pastor must be that had to do with being a role-model. The right to judge these matters was firmly held by others, especially, of course, those being ministered unto. The bottom line was not “my spiritual gifts and call,” but the approval those who would call upon me to exercise the gifts. If the phone stopped ringing the pastor was done. Decisions to pick up the phone and call a pastor were never made officially by a committee or tribunal; those meetings came much later, if needed to mitigate some catastrophe. The pastor was the first to know when the phone stopped ringing. But in those days before social media it was rare for the pastor to be told why trust had disintegrated. This dynamic is not limited exclusively to pastors and religious leaders. Anyone whose position depends on acceptance by the public can find that eroded. Teachers, civic officials, celebrities, and even war heroes can sink without warning or recourse. Some are in a position to fight back and others are sufficiently buffered to outlast the incoming tsunami, but many are destroyed. Social conformity is demanded as the price for social acceptability. Nonconformists must have some immense skill or leverage. The infuriating thing about this is how little facts count for anything. When a teacher is accused of racism or favoritism, if social media get wind of it, the storm may grow unstoppably. Neither circumstances nor accuracy matter. Only a counter-storm of overwhelming support has any chance, and those who could help are often hesitant to get involved and become collateral damage or targeted as co-conspirators. Social media have made this much worse and more pervasive. Social media are invasive, relentless, unforgiving, and ruthless. They thrive on the very energies that destroy discourse and courageous inquiry. People these days feel entitled to freedom from discomfort, let alone intimidation. They presume they have the right to protect themselves by any means, even at the cost of failing to know what the world is like. This is ominous. At this rate things are going to continue toward repression, fear, and disregard for “others” as well as disdain for the very possibility that truth may exist outside one’s bubble. [Thanks to Anne Applebaum for the quote at the top of this essay from her August 31, 2021 Atlantic article “The New Puritans”.] Nothing recently has impressed me more that sacred space is widely misunderstood than a merit-making ceremony in our village last Tuesday morning at the cremation ground.

The merit-making was to symbolize the merit being garnered by those who had contributed to repairs on the crematorium. Ban Den Village raised 13,000 baht ($400 US) which is the last part of the funds needed to fix the facility. A chapter of Buddhist priests chanted stanzas and then food was eaten. Compared to the efforts and events connected with the reconstruction of the crematorium in 2015 this project is minor. Nevertheless, it was not to be undertaken without due care. Merit-making alone does not cover the reasons for the ceremony. What is going on in spaces like that? A cremation ground is associated almost exclusively with death. It could not be otherwise. Nobody would ordinarily think of using the ground for anything other than cremations. Since a cremation disintegrates a human body, so the story goes, the spirit / ghost is deprived of its accustomed place to be. If they have not gone on (into heaven or hell depending on their accumulated merit) to prepare to be reincarnated, they may be lingering in the cremation precincts. “Placidly haunting” is the least of the things these ghosts may be up to. But the cremation ground has been repeatedly neutralized by solemn and extensive ceremonies. Buddhist monks maintain that death is merely one of the unavoidable conditions and consequences of life. In one of the Lord Buddha’s earthier sayings he posed that there are two inevitable human experiences: defecation (the translation I came upon avoided the Pali word for shit) and death. One discipline undertaken by serious monks is to contemplate the decomposition of corpses (or sometimes just skeletons). Itinerant monks sometimes seek cremation grounds for an overnight campsite. This is all about much more than desensitizing monks about death. Monks are to be masters of the specter of death; at least the more adept of them are. Without extending this essay to include several other examples of the yin-yang nature of haunted-holy places, let’s agree that those are liminal-threshold spaces, as forests are in many cultures. Cremation grounds in Thailand are typically in wooded areas called “paa chaa” ป่าช้า (implying literally, “a forest for lingering”). The dual nature of cremation grounds could not be clearer. What is not so obvious in our time is that all really sacred spaces are that way. Holiness is indivisible from frightfulness. To be in the presence of the Holy is to be terrified and also to be transformed beyond that immobilized and debilitated state. One is never the same after that. Talmudic Judaism, Medieval Christianity, Vedic Hinduism, and mystical Islam all comprehend the awesome and compassionate dual-nature of the Holy. Wherever the Supreme has stood, sat, or lain is sacred, and to touch such a place is perilous as well as pious. Piety, as mystics know, is fraught with ecstatic agony. One must approach treacherous Holy places with respect; but respect is only the beginning. Indeed, one can never know what sacrifice might be required when one enters the Holy of Holies. Christianity early on conceptualized the holy event as a sacrificial meal to recapitulate the supreme divine-human encounter. That simple meal first eaten by Jesus with his disciples was embossed with layers of ritual sanctification which Protestantism sought largely to remove in order to get back to the essential meaning of “Christ with us.” The Enlightenment castigated all mystery as superstition and began to eradicate it. We have now come to the point where there is no longer such a thing as sacred space. Churches are designed as refuges. They are sanctuaries. They are places to escape the confusion and conflict going on outside. They are places of serenity and community. This downgrading of holy places (which is happening throughout most cultures in our time) has come at a price. Domesticated holiness is impotent. When we no longer value the transformation that comes from encountering the stunning and awesome Holy, and refuse to see our stricken and naked souls clearly, we succumb to the illusion that there is nothing worthy of awe. But our friendly gathering places (or their virtual substitutes into which we can zoom or chat) lack the power we need to meet the realities that linger in the shadows to assail, betray, and beguile us. Deprived of sacred spaces we become lethargic and inept. Lulled by the deceit we have cultivated that there is nothing to fear, we succumb to the illusion that there is nothing worthy of awe. Trapped in our naiveté we are overwhelmed when the shadows congeal. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed