|

There are four realms of discourse about faith in the United States that should be kept separate even though that is hard to do. These areas overlap, so activity may involve more than one domain. Social scientists study these practices as discrete issues, which tends to ignore simultaneous operations and blur conclusions. Theologians, religionists and students of comparative religion must be able to synthesize the whole picture, even the gestalt, which tends to become argumentative after a while. Meanwhile, most people are content to lump all their beliefs together.

The four realms are religion, civil religion, spirituality, and folk-faith. DEFINITIONS Religion in the USA is understood to be the purview of various traditions with their structures, traditions and rituals enclosed in boundaries of their own construction. Religions have narratives that are shared widely among all adherents to the religion, which connect people to the sacred. The purpose of a religion is to sustain and communicate a key, fundamental truth (or body of truths), the way to derive the benefits of knowing this truth, and the implications for a life modified to comport with that truth. The complex symbolisms in religions are to facilitate retention of the truth by initiates and to provide foci for communities of believers, and to help them bridge the chasm between the mundane and the holy. North America has been host to nearly all of the world religions as well as sub-divisions of them. Several indigenous religions emerged as well, e.g. the Mormons. It is accepted in America, following Christian hegemony, that one cannot be a member of more than one formal religion. Civil religion is a faith-based cluster of concepts that presume to account for the history and unique culture of the American people as a nation. This national narrative is not compiled into a fixed canon but is reiterated as legends and truth agreed to by consensus. American civil religion incorporates symbols (such as the flag, and the national anthem, to name but two), and patriotic shrines and landmarks where a “reverential” level of patriotism is mandated (as at the “Tomb of the Unknown Soldier”). These symbols and shrines may only vaguely refer to the national narrative. National observances tend to evolve into holidays of three types: those that support the fundamental principles of American civil religion (e.g. Memorial Day and Independence Day – the 4th of July, and Thanksgiving Day), those that contradict American civil religion (e.g. Martin Luther King’s birthday), and those that become irrelevant to American civil religion (e.g. Labor Day and the Washington Monument). In times of cultural threat civil religionists recruit formal religious leaders and transform organizations in the cause of patriotism to perform civic duties. Whenever civil religion is a dominant influence, separation of “church and state” is obscured. Spirituality has to do with how individuals integrate the experiences and components of life in order to live effectively and optimize a sense of meaningfulness and fulfillment. Spirituality is concerned with strategies for synthesizing insight, discovering peace, and maximizing life. Spiritual strategies usually involve training in mind control through physical deprivation or exertion, limited sensory input to deepen concentration or sensory overload to open the mind, and/or expanded knowledge and cognitive capacity leading to insight. American spirituality is eclectic and optional. It often incorporates physical exercise or some dietary regimen in the name of being holistic. Folk-faith in the USA includes a wide range of generally held beliefs and narratives about life and death, common sense, and the natural order. It is the character of folk-faith to hold these beliefs tentatively, while deriving assurance from them. Some of these beliefs are held in spite of official opposition or scorn (e.g. that suicide is a valid option rather than unbearable, interminable suffering), but other folk beliefs manage to acquire a measure of agreement (e.g. that when we die we will be reunited with those we loved, an assurance that will generally be reiterated by clergy at an American funeral). Folk beliefs are subject to waves of popularity. Much mischief results from failing to recognize how these realms of faith function. Some of the trouble is deliberate. Political powers benefit from manipulating public emotions about faith issues. It makes a difference that formal religions have a canon of scripture, but civil religion does not. That can be and has been exploited. Most of the confusion is inadvertent, although sometimes damaging. Now that personal spirituality is indistinguishable from formal religion, the fact that spiritual development is understood to be a personal choice has undermined traditional religion’s ability to arbitrate between persons’ inclinations and cultural values, for example. In the end, the muddle manages to destroy the very thing faith is supposed to provide, freedom to believe. Faith systems can coexist as long as they respect each other. But confusion and belief cannot coexist.

0 Comments

February 16 is recalled as the founding date of Payap University. This is the date that the committee met and took action to establish an educational institution called “Payap Christian College”. When

this was proposed to the Ministry of Higher Education [now a unit of the Ministry of Education] they had us drop the word “Christian” and use the name “Payap College” for our establishment. This year was the 43rd anniversary of our founding, to which all past presidents and retired personnel were invited to join. The university was honored to have the Treasurer of the Foundation of the Church of Christ in Thailand preach that day. Going back into the past, Payap College began with the McGilvary Seminary, established in May 1889 and the McCormick School of Nursing and Midwifery, founded in 1923. Payap College had its opening ceremony on June 22, 1974 and was elevated to university status in 1984. It is the first private university in Thailand, and has three campuses: Kaeonawarat Campus (home of the seminary, faculty of nursing, and college of music), Mae Kao Campus (the main campus), and Crystal Springs Campus (not used at present). Payap University was established by the Foundation of the Church of Christ in Thailand in 1974 to manifest God’s love, faith, humanity’s reverence for God, and human-kind’s mutual support. This is expressed in the motto, “Truth and Service”. We strive for academic excellence and morality leading to understanding, shining forth in the truth of life and enhancement of good attitudes in service to society. 38,118 students have graduated from Payap in the past 43 years. [These paragraphs are from two documents prepared in time for the anniversary.] A consensus seems to be developing among analysts that one of the triggers for the conservative-reactionary backlash going on in the USA and Europe is fear that is generated by the inability to adjust to rapid cultural change. Things are changing too fast for people to adjust, and of course it appears that the future will alter the centers of power away from those who now hold it and benefit from it.Trump, Brexit and the rise of ultra-right political parties are attempts to reverse the change.

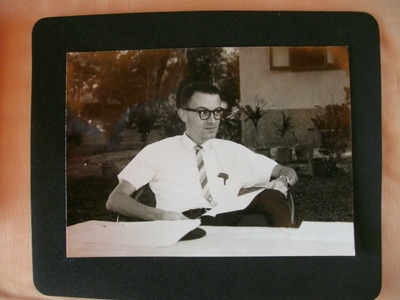

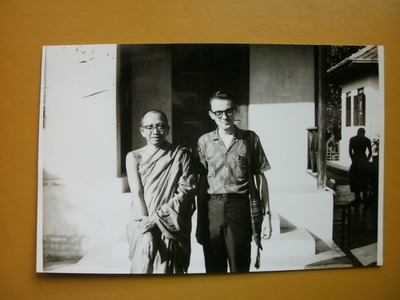

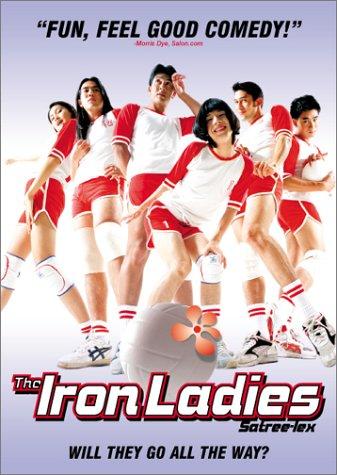

Some of the issues are international in scope: migration and refugee flow is changing the “color” of traditionally light-skinned populations; LGBT emergence as a socio-political force is changing the moderators of cultural norms; pressure from women to gain fair participation in decision-making is changing male-dominance; religious diversity following channels of migration as well as postmodernist patterns of independent thinking are changing the most visible cultural indicators (viz. churches, cathedrals and other religious institutions and even their edifices); and widespread skepticism about the role of government and the spread of globalization being beneficial is changing popular support for the way international and inter-cultural relationships operate. As a whole these changes are so vast and vague that they cannot be grasped. They are mysterious and frightening. Fear leads to irrational reactions, which can easily be counter-productive. When people are gripped by amorphous apprehension, small incidents can loom large, opinions become fluid and volatile, conspiracy rumors run rampant, and charismatic voices saying, “I will lead you out of this,” get attention. Rather than re-run explanations about this and opinions about how to deal with it, I want to share reminiscences about the summer of 1969, where I first encountered my own inability to adapt to ominous change. [The pictures above are from just before I left Thailand that year.] I was certainly not alone in that, but here is my story of two incidents that shook me: In August 1969, I arrived back in Chicago from four years in South East Asia watching governments collapse and under threat in Indonesia, Burma, Laos, Vietnam and Malaysia from the onslaught of Maoist Communism during the height of the horrifying Cultural Revolution. Chicago was traumatized and polarized. Mayor Richard J. “Hizzonor” Daley had used violent force to protect the Democratic National Convention (i.e. “The Establishment”) from Vietnam War protestors the year before. My own seminary in the Lincoln Park neighborhood had been “occupied” and closed down by the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican street gang, a.k.a. “freedom movement” against “The Establishment”. Scores of gatherings and marches were held to protest US actions in SE Asia and the Vietnam War. I thought I had a small set of useful stories about how brave but afraid people were in the Philippines and Thailand, to balance the discussion, or add to it a more human perspective. I found no impartial forums or seminars on the Vietnam War. Nobody wanted to hear stories that undermined their rage, and they were raging pro and anti. I felt isolated and threatened in the city I thought of as my urban home. It was the first experience of my life where discourse on a major issue was illegitimate. In June 1969, just months after the Six Day War between Israel and the United Arab Republic, we stopped off to visit dear family friends in Cairo. The city was sand-bagged and preparing for an invasion from Israel, which had, in fact, made the preemptive air strikes that began the war two years earlier. We met with several people who told us stories of relatives being killed, wounded or made prisoners of war, and of horrifying incidents. Not long after that, I was invited by a Reformed Jewish Congregation in Shaker Heights, Ohio, to be on a panel discussion on the Six Days War. It was beginning to be clear that the war had tipped the balance of power and delivered huge amounts of territory into the control of the State of Israel. Who “owned” that land depended on how legitimate the 6-Day War had been. As invited, I filled my fifteen-minute slot with stories about how devastating the war had been to families in Egypt. I had been misinformed by the organizers of the event. There was no appetite, even among those sophisticated Jews and a few Christians, to hear from the Egyptian or Palestinian side. “The Egyptians got what was coming to them.” At the end of the workshop I had to be escorted to my car for my own protection. It was my second major experience of unwelcome discourse. The summer of 1969 was a time of turbulent change and I had trouble adjusting to it. On July 20 the USA pulled ahead of the USSR in the “Space Race”. Neil Armstrong took “one small step for mankind” from the bottom rung of the Apollo 11 moon-lander onto the moondust and then he and Buzz Aldrin collected 50 pounds of rocks. There was some doubt about who was winning the nuclear arms race, but the space race was clearer after July. Watching those grainy black and white pictures from the moon, I realized that “now things are different”. It was a whole new era and our perspective about life on earth would never be the same. The war in Vietnam was going all wrong with the USA stepping in to defend the corrupt, dictatorial regime in Saigon for reasons that were unclear and hidden but had to do with natural resources and the Cold War to prevent Communism from taking over the world. John Foster Dulles had convinced us that SE Asia was like a string of dominos. If one fell, they all would fall. In 1969 the dominos were teetering precariously. A specter hung over hundreds of Thai colleagues, students and acquaintances that I considered dear friends. My fear for them was deep and existential. On August 15-18 I was again shaken, unexpectedly, by a cultural earthquake. The epicenter was at Woodstock. It was the dawning of the Age of Aquarius and a whole new wave of cultural change. It was the official end of Modernism and the beginning of Postmodernism, but that was not yet clear. At the time we thought Elvis Presley and the Beetles had brought cultural change, but they were really still on the threshold. I can say it now, Woodstock alarmed me. I no longer belonged to a unified culture. I was no longer in a position to be a moderating agent, as I had imagined I might be when I finally settled into my role as a Presbyterian pastor of a “tall-steeple” church. Intuitively I knew, by 1970 the change was overwhelming. What does one do? There are, briefly, four options when one is attacked or threatened. Fight, retreat, surrender, or negotiate. When I was confronted by overwhelming change, my strategy was to retreat and then negotiate. First, throughout the fall and winter of 1969 and 70 I withdrew into my cave, working on a master’s degree and lying low. Then I thought I might be able to work out a rapprochement with the cultural quake, at least. Perhaps I could be a mediating influence in specific instances between anti-war and anti-communist partisans and between the Hippy-Jesus Freaks and the traditional church. The full impact of the cultural change had not yet hit me. It took me several years to learn the lessons of the summer of 1969, that THIS cultural shift had changed the dynamics of social formation. Communication has never been the same since then. Ethnic divisions leading to tribalistic “ethnic cleansing,” and fragmentation of cultural entities leading to crumbling borders and global neo-liberalism have developed new realities. Fighting this change is what the resurgence of conservative alt-right alliances are about. They will fail, but they may precipitate another war first. Surrender to cultural change is the only realistic course of action, and the only one where change agents have a chance to undo the lethal trajectory of tribalism and neo-liberalism. But be warned: rational discourse will not work wonders as it used to do. “The Iron Ladies” was a surprise box office hit in 2000 before a new round of cultural suppression began in 2002. That crack-down was ineffective insofar as its attempt was to curtail public acceptance of gay, kathoey and trans persons into occasional prominence and public acclaim. “The Iron Ladies”, directed by Yongyoot Thongkongthun, is a light-hearted comedy inspired by the nationally-known success, three years earlier, of a volley ball team from the northern city of

Lampang. The team contains a variety of queer players when the previous players dropped out rather than be coached by a woman (a “tom” they claimed [using Thai slang for a lesbian, equivalent to “dyke” as the English subtitles say]). The coach accepts two trans players and so all the boys quit except one who becomes the team captain. Bee, the coach, has to make a team out of them but the obstacles are formidable, including: personality peculiarities, family objections, opposing teams’ ridicule, and then official obstinacy. The team coalesces, wins its way to the national championship and then seems to be blocked by the homophobic, misogynistic tournament organizers, until fans overwhelm them and the main bad guy knocks himself out, so the championship can proceed and be won by the “iron sisters”. As Yongyoot tells the story, key players being recruited and installed into the team have to overcome impediments at home, on the court, and in their own hearts. A closeted gay male player has to come out and openly defy his family to play, while another family is giddy with joy to have their kathoey-trans child going on this adventure. The coach has to confront officials about their rules being made up as they go along – no one dreamed of men playing against a team presenting themselves as an odd form of women. Society, as “The Iron Ladies” portrays it, is coming to terms with gender diversity, but the energy is entirely from the grassroots. The issue is where do these people fit into society and into national culture? Apparently, it will take acts of defiance to make it happen. In retrospect, “The Iron Ladies” is much about defiance. Yongyoot is quite willing to pander to stereotypes. He doesn’t hesitate to have a player come unhinged when she breaks a fingernail. One is reminded of flamboyant Armand in “The Birdcage”. It seems hard to find normal queers in movies of that time (1996). We are all exaggerated. In “The Iron Ladies”, before the final climactic contest, every one of the players and most of their foils has been identified as a type. There is a lack of subtlety about the obedient son, the raging homophobe, the flaming queen, the doting parents, the controlling father, and the pathetic misogynist. There is a satisfying predictability about how those who rise defiantly achieve success and those who do not wither in defeat. The volleyball teams that the ladies face seem incapable of respecting their opponents or accepting defeat gracefully. The fans, in particular, are defiant. Yongyoot clearly signals that sexual minorities have fights to wage. The main impact “The Iron Ladies” makes is not through its blunt messages. Film critic Roger Ebert disagreed with almost everything about the film except the characterization of Bee, the coach. He felt the film was about forty years out of date in its representation of gender diversity and especially its ludicrous stereotyping. Still, the film was the second highest grossing Thai film at the time, a record it held for more than a decade. It spawned two sequels (which were not as good, although profitable by Thai standards). What Ebert could not know when he wrote his review, is that “The Iron Ladies” was to be barrier-breaking in Thailand and East Asia. It was a movie that showed gender diversity positively, showed public acceptance of it, disparaged official repudiation of it, and then even as the credits rolled said “these LGTK people can live happy productive lives after their volleyball victory, in life among you.” No government publication, to this day, makes those claims. Moreover, the movie and its success helped fulfill those assertions. It is a help to be a national champion or a phenomenal success if one is to gain public acceptance. But the bar is lowered as more and more of the public get acquainted with the new normal. The big story of “The Iron Ladies” is about the public perception and positive response. It began with the crowds at the tournament, but spread through the Kingdom of Thailand. These queers had fans from Chiang Rai (far north) to Trang (far south) and that had never happened before. Arnika Fuhrmann of Cornell University puts it this way, “[the film’s] greater emphasis lies on engendering national discourses of advocacy regarding homosexuality and transidentitarian positions.” She concludes, however, that films like “The Iron Ladies” are superficial in that their “potential for radical figurations of queerness remains limited.” |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed