|

A consensus seems to be developing among analysts that one of the triggers for the conservative-reactionary backlash going on in the USA and Europe is fear that is generated by the inability to adjust to rapid cultural change. Things are changing too fast for people to adjust, and of course it appears that the future will alter the centers of power away from those who now hold it and benefit from it.Trump, Brexit and the rise of ultra-right political parties are attempts to reverse the change.

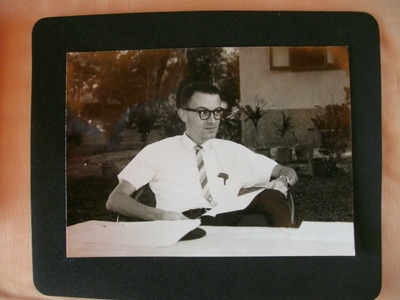

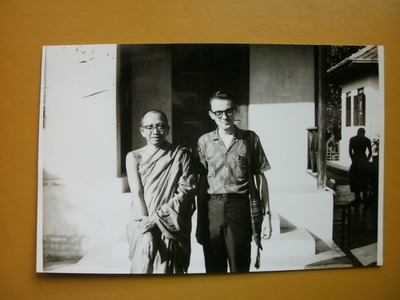

Some of the issues are international in scope: migration and refugee flow is changing the “color” of traditionally light-skinned populations; LGBT emergence as a socio-political force is changing the moderators of cultural norms; pressure from women to gain fair participation in decision-making is changing male-dominance; religious diversity following channels of migration as well as postmodernist patterns of independent thinking are changing the most visible cultural indicators (viz. churches, cathedrals and other religious institutions and even their edifices); and widespread skepticism about the role of government and the spread of globalization being beneficial is changing popular support for the way international and inter-cultural relationships operate. As a whole these changes are so vast and vague that they cannot be grasped. They are mysterious and frightening. Fear leads to irrational reactions, which can easily be counter-productive. When people are gripped by amorphous apprehension, small incidents can loom large, opinions become fluid and volatile, conspiracy rumors run rampant, and charismatic voices saying, “I will lead you out of this,” get attention. Rather than re-run explanations about this and opinions about how to deal with it, I want to share reminiscences about the summer of 1969, where I first encountered my own inability to adapt to ominous change. [The pictures above are from just before I left Thailand that year.] I was certainly not alone in that, but here is my story of two incidents that shook me: In August 1969, I arrived back in Chicago from four years in South East Asia watching governments collapse and under threat in Indonesia, Burma, Laos, Vietnam and Malaysia from the onslaught of Maoist Communism during the height of the horrifying Cultural Revolution. Chicago was traumatized and polarized. Mayor Richard J. “Hizzonor” Daley had used violent force to protect the Democratic National Convention (i.e. “The Establishment”) from Vietnam War protestors the year before. My own seminary in the Lincoln Park neighborhood had been “occupied” and closed down by the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican street gang, a.k.a. “freedom movement” against “The Establishment”. Scores of gatherings and marches were held to protest US actions in SE Asia and the Vietnam War. I thought I had a small set of useful stories about how brave but afraid people were in the Philippines and Thailand, to balance the discussion, or add to it a more human perspective. I found no impartial forums or seminars on the Vietnam War. Nobody wanted to hear stories that undermined their rage, and they were raging pro and anti. I felt isolated and threatened in the city I thought of as my urban home. It was the first experience of my life where discourse on a major issue was illegitimate. In June 1969, just months after the Six Day War between Israel and the United Arab Republic, we stopped off to visit dear family friends in Cairo. The city was sand-bagged and preparing for an invasion from Israel, which had, in fact, made the preemptive air strikes that began the war two years earlier. We met with several people who told us stories of relatives being killed, wounded or made prisoners of war, and of horrifying incidents. Not long after that, I was invited by a Reformed Jewish Congregation in Shaker Heights, Ohio, to be on a panel discussion on the Six Days War. It was beginning to be clear that the war had tipped the balance of power and delivered huge amounts of territory into the control of the State of Israel. Who “owned” that land depended on how legitimate the 6-Day War had been. As invited, I filled my fifteen-minute slot with stories about how devastating the war had been to families in Egypt. I had been misinformed by the organizers of the event. There was no appetite, even among those sophisticated Jews and a few Christians, to hear from the Egyptian or Palestinian side. “The Egyptians got what was coming to them.” At the end of the workshop I had to be escorted to my car for my own protection. It was my second major experience of unwelcome discourse. The summer of 1969 was a time of turbulent change and I had trouble adjusting to it. On July 20 the USA pulled ahead of the USSR in the “Space Race”. Neil Armstrong took “one small step for mankind” from the bottom rung of the Apollo 11 moon-lander onto the moondust and then he and Buzz Aldrin collected 50 pounds of rocks. There was some doubt about who was winning the nuclear arms race, but the space race was clearer after July. Watching those grainy black and white pictures from the moon, I realized that “now things are different”. It was a whole new era and our perspective about life on earth would never be the same. The war in Vietnam was going all wrong with the USA stepping in to defend the corrupt, dictatorial regime in Saigon for reasons that were unclear and hidden but had to do with natural resources and the Cold War to prevent Communism from taking over the world. John Foster Dulles had convinced us that SE Asia was like a string of dominos. If one fell, they all would fall. In 1969 the dominos were teetering precariously. A specter hung over hundreds of Thai colleagues, students and acquaintances that I considered dear friends. My fear for them was deep and existential. On August 15-18 I was again shaken, unexpectedly, by a cultural earthquake. The epicenter was at Woodstock. It was the dawning of the Age of Aquarius and a whole new wave of cultural change. It was the official end of Modernism and the beginning of Postmodernism, but that was not yet clear. At the time we thought Elvis Presley and the Beetles had brought cultural change, but they were really still on the threshold. I can say it now, Woodstock alarmed me. I no longer belonged to a unified culture. I was no longer in a position to be a moderating agent, as I had imagined I might be when I finally settled into my role as a Presbyterian pastor of a “tall-steeple” church. Intuitively I knew, by 1970 the change was overwhelming. What does one do? There are, briefly, four options when one is attacked or threatened. Fight, retreat, surrender, or negotiate. When I was confronted by overwhelming change, my strategy was to retreat and then negotiate. First, throughout the fall and winter of 1969 and 70 I withdrew into my cave, working on a master’s degree and lying low. Then I thought I might be able to work out a rapprochement with the cultural quake, at least. Perhaps I could be a mediating influence in specific instances between anti-war and anti-communist partisans and between the Hippy-Jesus Freaks and the traditional church. The full impact of the cultural change had not yet hit me. It took me several years to learn the lessons of the summer of 1969, that THIS cultural shift had changed the dynamics of social formation. Communication has never been the same since then. Ethnic divisions leading to tribalistic “ethnic cleansing,” and fragmentation of cultural entities leading to crumbling borders and global neo-liberalism have developed new realities. Fighting this change is what the resurgence of conservative alt-right alliances are about. They will fail, but they may precipitate another war first. Surrender to cultural change is the only realistic course of action, and the only one where change agents have a chance to undo the lethal trajectory of tribalism and neo-liberalism. But be warned: rational discourse will not work wonders as it used to do.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed