|

Message for the New Generation

It’s not supposed to be like this. There is not supposed to be any controversy about how wrong it is for a teen-age young adult to kill 18 ten-year-old kids and their teacher in a classroom. It is wrong. Period. There is not supposed to be a danger of being killed when you go to a grocery store in Buffalo. Another 18-year-old with a killing machine did that; he was a white supremacist and his target victims were Black. He talked a lot about doing this before he did it. There is not supposed to be a threat to Taiwanese-Americans in their Presbyterian Church, from another immigrant from Taiwan who planned not only to kill these strangers because they were from Taiwan, but also to incinerate the church where they were having dinner. There is not supposed to be an unprovoked invasion of a sovereign nation by its neighbor for any reason. Yet Russia invaded Ukraine and claims it is right to do so. There are supposed to be international law and powers to prevent such atrocities. There should not be a need for the President of the USA to reiterate the country’s commitment to assist Taiwan with military intervention if it is invaded by China. There is not supposed to be a national movement to control women’s sexuality. But such movements exist in several nations, and have for a long time. There is not supposed to be the possibility for a large Christian denomination to protect clergy who engage in illegal sexual activity. These goings-on over the last two weeks are not supposed to be happening. This is not how life is supposed to be. We do not have to put up with it.

0 Comments

What makes teaching in Asia perilous?

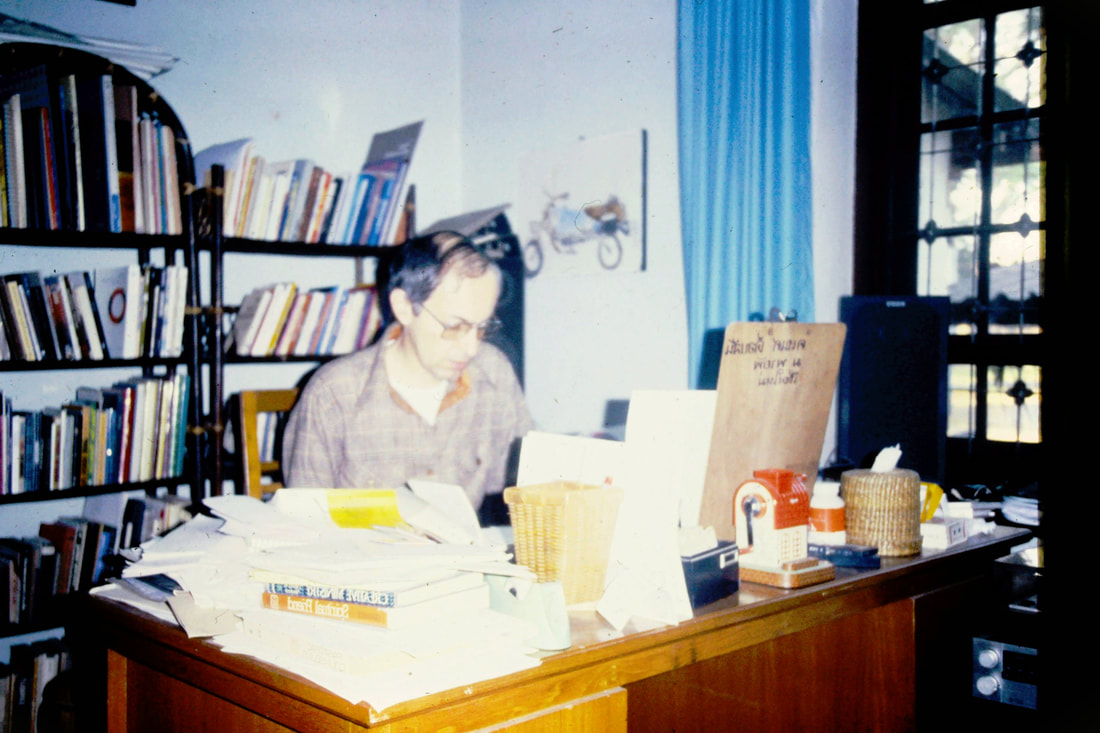

Sometimes it’s the need to conform one’s teaching to a political philosophy, or to stay out of politics entirely despite one’s subject matter. But that hasn’t been my experience here in Thailand. I am thinking of the way I was handled as we tried to require “English proficiency” for PhD and MA students following criticism from employers of previous graduates that they had expected our students to be more capable in using English than they had turned out to be. The administration was alarmed. So, we imposed “English proficiency” and a proficiency exam as requirements for graduation. It was my job, mainly, to develop this requirement and produce the courses and exams. Now, proficiency is a technical term in English as a Foreign Language. It is measured in levels from beginner to advanced, some 6 or 9 levels, each one taking about 200 (two hundred) hours of instruction and practice. That is too much to be suddenly added onto a degree program in some other field, such as “Advanced Nursing” or “Doctor of Hospital Administration.” Even moving students from one level to the next would be impossible. So, we first decided to simply produce a course and exam that showed that students could use English better than when they came to us. We had an entrance exam, and then an exit exam and if the student improved, great. But not all students were equally improved. We modified the course to clarify areas of competence: listening and comprehension, speaking, reading, and writing. Every time we taught the course, we tweaked it. But a couple of the PhD students who were medical doctors aiming for medical administration degrees (2 out of about 20 students) complained that the exam included questions about a reading that had not been presented in class. Even though it was in the course outline that “ability to analyze English writing to determine the meaning” was the course objective, which is not the same as “remembering what was discussed in class”, the administration became alarmed that out PhD students were unhappy. Immediately, without regard for prior approval of the course outline and description of the lessons, I was required to re-grade the exams and make sure those PhD students all passed. From then on, we had to re-write the English courses to include only material from the textbooks (not more than 2 or 3 pages, actually, from 400-page textbooks) and make sure that the exam had nothing new, no more “proficiency” but only “accomplishments” were to be measured. This went on for two years. There was continual readjustment of the courses as they were going on, based on student feed-back. It seemed painfully unfair and organic, as if nothing could be depended on. What mattered, as it turned out, was student satisfaction much more than future employer satisfaction. Even end-of term evaluations were based on what the institution needed to show, how the overall impression about the institution would look. Twenty years prior to that I went through another disappointing attempt to be effective and creative. I was teaching institutional management to master’s students. Up to that point, we did not have practical courses at the master’s level because the effort had been to produce effective functionaries. But I thought I had stumbled on a way to improve the instruction to produce leaders who would know not only what they were supposed to do but why things worked as they did, which would lead to discovering better ways to get things done. For example, if the course was about administration, then students ought to be familiar with literature that was available about management, and able to go into the field and examine how things were operating. So, our students scattered out and came back with new perspectives. No longer blocked by old ideas of adhering to manuals of operations, they reported that dysfunction had nothing to do with loyalty to the establishment but everything to do with clan and ethnic expectations. So, our management questions needed to be reformulated. Establishment efficiency could not be achieved and sustained without attention being paid to what actually mattered to the people who did the work and were the constituency. I lasted only to the end of that year. Our university did not need a new way of perceiving its objective, which was to educate masters who would be leaders. Actually, that notion was so irrelevant it was not even the reason I was replaced as teacher of the practical courses in the master’s program. I was replaced because there was another man who needed a job, and teaching “the manual of operations” was what he could do. We needed him because he could attract students and because he was well known. In thinking about this, larger principles came in sight. What always mattered was the reputation of the institution and its ability to recruit students. What did not matter was the integrity of the instruction as it pertained to course objectives and outcomes. It also did not matter that teachers were treated with disregard to their dignity or qualifications. What was important is that the institution and its leaders were always “on top of things” even though they were burdened by less competent underlings. The institution and its leaders were what mattered. The issue was institutional esteem. I have now retired after nearly 60 years of contact with educational institutions in Thailand. In my leisure I have reflected on how things work here. There are differences in institutional culture, especially with regard to those massive government-connected institutions and private ones. But one thing that seems to be true in all of them is that the thing to be defended from challenges of any sort is the institution and its leaders. Sometimes it is not immediately apparent who is the “leader” since the one in the front office may not be the one in charge. It’s a hierarchical system built on a pyramid that gets steeper and lonelier at the top. Some leaders stay in charge by trying to micro-manage everything; hours are long and physical wear and tear are inevitable. Some leaders try to build a team to which they listen and use as surrogates or buffers, extensions of their own authority (because the country as a whole understands hierarchical administration to the exclusion of all others). Some leaders consider themselves temporary place-holders, something like the zero in mathematics; they are helping the institution through a transition, usually between what was and something quite similar to that which was. It is not dangerous to be a teacher here in Thailand. There are no spies in the classrooms reporting any suspected deviance to political authorities, no batteries of surveillance cameras in the rooms and hallways, as in neighboring China. There are no midnight raids rounding up teachers and sending them to prison or making them disappear forever, as in neighboring Myanmar. There are no parents forming vigilante groups to police teachers, ban textbooks, and take over boards of education, as in the USA, causing teachers to resign in droves. The parameters are culturally specific: students are to be treated properly, as students at the very bottom of the pyramid, and the institution and its leaders are to be supported and defended as necessary. All service institutions function on a similar principle. The system is to insure institutional esteem. It helps to know that. On April 30, 87 years ago, the road to Doi Sutape Temple was opened and a car traveled up it for the first time. This, in my estimation, was the most momentous road opening in Chiang Mai history.

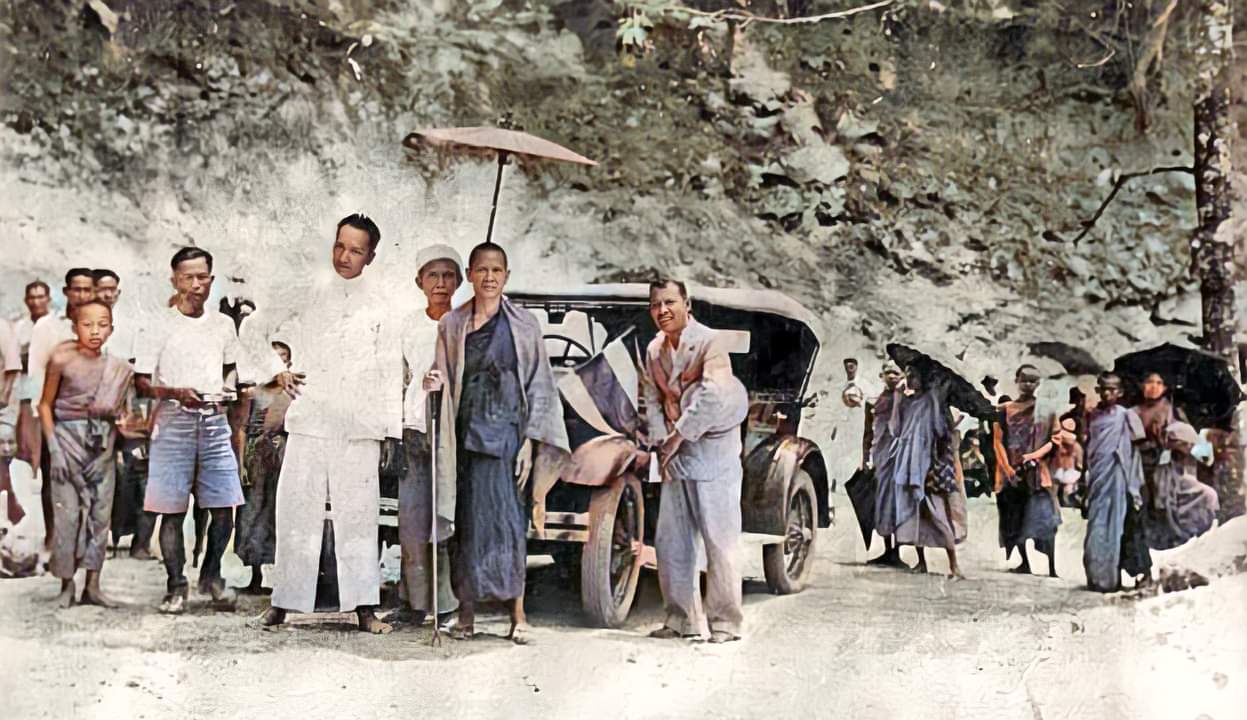

The construction of the road was a significant undertaking, begun at the behest of Kruba Srivichai, abbot of Wat Suan Dawk at that time. The temple on one of the peaks of Sutape Mountain immediately west of the city of Chiang Mai was neglected and hard to reach, although it presumably contained a major relic of the Lord Buddha. The relic’s twin was at Wat Suan Dawk. This symbolically linked the two temples. What Kruba Srivichai proposed is the people build the road as a merit-making undertaking. The project was begun on 9 November, 2477 with a ceremony performed by the abbot. For the next 5 months and 22 days thousands of people took hand tools and scraped a roadway around the mountain to the base of the 325 step stairway leading up to the temple building and chedi. Then, on 30 April 2478 (1935 AD) the road was completed enough to allow the first car to pass over it, carrying Kruba Srivichai. The trip began with a formal ceremony in which the venerable Kruba lit candles in honor of the Triple Gems, with Lord Kaew Nawarat the ruler of Chiang Mai in attendance. What makes this event most important is the way it indicated how important Kruba Srivichai was in the estimation of the people, who responded in their multitudes at his beckoning, despite the fact that the hierarchy (both political and religious) in Bangkok were trying to suppress him. He had been placed under house arrest for his outspoken resistance to Bangkok’s attempts to do away with Buddhist practices that were not under Bangkok’s control. He obstinate in his efforts to preserve a measure of Lanna character. He had huge support for whatever he undertook. The success of the road-building sent a powerful signal that Chiang Mai needed to be handled differently than had been attempted. Today, Doi Sutape is Chiang Mai’s most important pilgrimage destination. 30 years after the road was completed, HM the King constructed a palace residence a few miles further up the mountain beyond the temple and spent extended time there each year for several years, showing in concrete and roses that he was king over the north as well as the rest of the country. People barely remember how the nice road, now well paved and easy to traverse, was first of all a rebellious act. But some do. Every year on April 30 someone brings out old pictures of the day Kruba Srivichai opened the road and ascended to the top of the hill overlooking the whole valley. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed