|

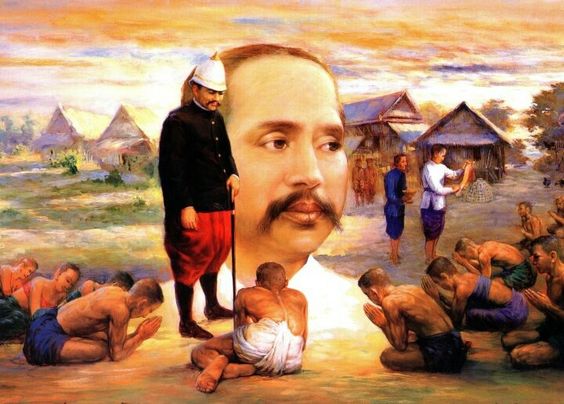

The emancipation of Thai slaves in 1905 was initially a very unpopular edict, especially among the slaves themselves in Lanna, the northern region of Thailand and adjoining principalities. This inconvenient fact is never explained in textbooks and is being gradually obliterated from the national narrative for a number of reasons.

1. The standard narrative exalts the King of Thailand for doing away with slavery as it was being eliminated by his contemporaries in Europe and the Americas. The ending of slavery was a glittering example of his benevolent enlightenment and modernization. 2. It is unpopular after several decades to remember that the inclusion of the Lanna Kingdom into the Empire of Siam involved extensive cultural suppression and shifts of power into the hands of the Bangkok elite. 3. The most potent resistance to the centralization of authority came from exalted Buddhist religious leaders. This remains marginally true today in the North, and even more so in the Isan (Northeastern ethnic) region. The official account of the freeing of slaves in Siam makes several points. (A) In the beginning of the reign of HM King Chulalongkorn in 1868 “more than 1/3 of the population were slaves” due to the fact that “it was so because there was the endless continuity of offspring slaves. They all were slaves for the rest lives. Traditionally children of slaves also became slaves.” (B) In 1900 it was decreed that slaves had to be given pay or credited for their labor at a fixed rate, the children of slaves were freed at age 21, and the value of a slave was fixed (a boy was worth about 10 baht and a girl was 8), but the enslavement was actually based on the amount of money owed to a creditor and repayment was established at the rate of not less than 1 baht a month. (C) In 1905, Royal Edict 124 “Slave Act” declared the end of the sale and resale of slaves. Reality was a bit more complicated. There were basically three kinds of slaves in 18th and 19th century Siam, and throughout the region. One kind was those who had been conquered in war. They were forcibly relocated to reduce their ability to continue opposing the victors. They also had certain valuable skills that were appropriated. At one time, for example, the village of Hang Dong, immediately Southwest of Chiang Mai, was a place where slaves from North Burma were resettled. They were considered valuable because they were paper-makers. They were exempted from corvee labor pools and other taxation, since they were “slaves”. In other words, their slave status was beneficial, and was resented by previous residents who were displaced and less privileged. This separate status from centuries ago still has influence in local politics today. The second kind of slaves were called money slaves, actually คนเงิน ”money-people” and not that “slaves”. They were debtors who had defaulted on their debts and were working off their indebtedness. They had used their own person as collateral. Although they could be indebted to wealthy patrons, it was temples in the north that were the biggest money-lenders. Therefore, temples had the largest number of these slaves. Historian Hans Penth puts this type of slavery into perspective. “Monasteries and their accumulated treasure served as banks: a person could borrow money from a monastery. Upon default he or she became a so-called money-slave … of the monastery until the debt was cleared. Being a monastery slave was better than a tax shelter: the person was exempt from taxes and also from corvee labor.” (Penth, Hans. A Brief History of Lan Na. Chiang Mai, silkworm Books, 2008. P. 118.) Being a slave offered significant protection and generally no greater travail than other serfs endured. A third kind of slavery, Penth reports, is “honorary slavery,” “those who freely attached themselves to a certain monastery or holy place and pledged to take care of a certain part or a certain building or Buddha image, which was considered an honor. Important monasteries would have more than a hundred of these honorary slaves.” (Penth, p. 118). All these kinds of slavery gradually ended, but not gladly. “Many of these changes were bitterly resented and even opposed, not only in Lan Na. The time-honored bondman or serf system (in the West usually called a slave system though these slaves were generally well treated, in particular in Lan Na) was an accepted social and religious institution. … With the gradual abolishment of the system the creditor felt that now he had to pay wages to a person who actually owed him money. Also for hundreds of years it had been a very meritorious act to forsake the service of one’s bondman and to present him to a Buddha image in a monastery, so he could serve the image. This great source of making merit was now closed.” (Penth, pp. 137, 138). The King’s enlightened benevolence and role as “beloved father of the nation” has to be seen also in the context of his political struggle to consolidate power in order to present a formidable resistance to British and French colonizers. His internal adversaries were powerful clans and vassal princes whose authority and power were derived from serfdom and economic slavery. What the King was doing was to undermine the economic foundation of the system that supported opposition to centralization of power. His attack was twofold. In addition to the elimination of using persons as collateral to secure loans, the King decreed the right of ownership of land throughout the empire to the people who actually farmed the land. Area princes were no longer land-lords and masters with life-and-death authority over the people under his (or sometimes her) sovereignty. This infringement of rights was offset by two major changes in the way Siam ran. People could no longer use their persons as collateral to acquire loans, but they could use their land as collateral. The former landlords could no longer derive income from the labor of the serfs, but they could become honored employees of the King as a whole new bureaucracy was developed to oversee the country and expand its agriculture and manufacturing, as well as centralized banking. When this shift became fully in effect, a large amount of the dissatisfaction with the end of slavery was reduced. By the 1930s, the only major resentment was on the part of religious institutions. After centuries people could no longer make great merit by turning over slaves or by becoming a slave attached to a Buddha image or temple precinct. What’s more, the entire Sangha hierarchy was being subjugated to central control under the King. Leading monks have resisted this, and continue to be the single most powerful bloc to unrestrained power by the military-royalist alliance.

1 Comment

On January 16 the Thailand Protestant Churches Coordinating Committee (TPCCC) issued a letter requesting every Christian church and institution in Thailand to send a letter to the committee by January 31 in which they state their opposition (or support) for the Civil Partnership provision of the proposed new constitution for Thailand. The committee will collect these letters and duplicate them to be presented to the office of the Prime Minister “and others”. The letter listed as co-signers in behalf of the TPCCC: The Church of Christ in Thailand, The Christian Fellowship of Thailand, The Baptist Foundation of Thailand, and the Foundation of the Seventh Day Adventist Mission in Thailand. It was addressed to all congregations, organizations and members of those church groups as well as those under the Roman Catholic Bishop’s Council of Thailand.

For those unfamiliar with the issue and the groups being referred to I add the following notes:

With all due respect, I suggest that the Thailand Protestant Churches Coordinating Committee reconsider their request that churches send letters of protest (or support) with regard to the Civil Partnership provision of the proposed draft constitution. The following are my reasons for suggesting the proposal is flawed: 1. Churches in Thailand have not had an opportunity to study civil partnerships from a Christian perspective because no thorough material has ever been published in Thai and no occasions have been provided for informed dialogue on this topic. It is unfair to ask churches to reply to any matter they have not studied. 2. This is a matter which many sectors of world Christianity have spent decades studying, even if churches in Thailand have not. It is clear that it cannot be responded to without extensive study. That study has led to heated debate, but a majority of churches who helped establish the Church of Christ in Thailand have concluded that civil partnerships and marriage are right and moral. There is now a large group of Christian denominations in favor of this form of marriage and family. 3. It is not easy to see any way in which the enactment of civil partnerships would have a legal impact on Christian churches in Thailand. Therefore, it must be that the churches on the TPCCC believe the issue is moral and that Christian churches should exercise a moral influence. However, the committee’s letter requests those who are highly motivated to express an opinion, not about a point of moral importance, but about a legal issue about which everyone already had a chance to express themselves when public hearings were going on. For these reasons, I respectfully suggest that the TPCCC refrain from creating a compilation of letters to be sent to the government. If it is time for the churches to take a stand about marriage equality and family life, then it is time to establish the opportunities and materials needed to study and debate this as other churches have done. If it is too soon for churches in Thailand to do that, then it is too soon for the churches to let a few voices speak for the whole church to the government. REMINISCENCES

Nothing, I believe, in the twentieth century, promoted Christian unity as widely as the annual observance of a week of prayers for Christian unity, given power and encouragement by the movement away from divisiveness growing out of the Second Vatican Council and the establishment of the World Council of Churches. The annual Week of Prayer for Christian Unity first began through the efforts of the cofounder of Graymoor Franciscan Friars, Paul Wattson, in 1908. During the same period Protestant leaders also proposed a festival of prayer for unity, and the two movements were combined into the present Week of Prayer for Christian Unity. Joint activities between the Roman Catholics and the Faith and Order Conference of the World Council of Churches led to decisions to hold a week (8 days) of prayers for Christian unity beginning on the day of the Feast of the Confession of St Peter and ending on the Feast of the Conversion of St Paul. Resources have been produced for the octave since 1968. In 2019 the week is from Friday January 18 to Friday January 25. My introduction to this week of prayers was in January 1966 when students from Chiang Mai University and their Jesuit mentors from Seven Fountains Student Center came to the Thailand Theological Seminary for a joint service. I understood it was the Catholics’ turn to conduct the service and for the Protestants to be hosts. For a few years the plan was to have the service alternate between these two institutions. As the next year approached, the Second Vatican Council was beginning to make an impact and ecumenism was much in vogue. I proposed that we might take this observance up a notch in 1967 by conducting a co-celebration of Holy Eucharist, a liturgy for which there was no established format and barely any precedent. The Rev. Dr. Kosuke Koyama and I were appointed to represent our seminary in making the suggestion to Father Andre Gomaine, SJ, of Seven Fountains. He listened nervously as Ko made the proposal enthusiastically and then said he would discuss it with the bishop. A few days later Fr Gomaine reported that, much to his surprise, the bishop had approved the idea. “I told the bishop that the Protestants want to have con-celebration of Eucharast as part of the service of prayers for Christian unity. The bishop was taking a shower and I was talking to him over the wall of the shower stall. The bishop agreed. I asked him if he had understood, and he said he had understood just fine but there should be no publicity about the event. Just do it.” Father Gomaine apparently felt trapped, but he worked with us in mapping out the liturgy. We divided the liturgy so that the parts emphasized by Protestants were done by Protestants and the parts most sacred for Catholics would be done by Catholics. Simply, the preacher was Ajan Prakai Nontawasee, a teacher in our seminary and soon to be the first woman to head a theological seminary in Asia and the first female Vice Moderator of the Church of Christ in Thailand. The consecration prayers (which I found out were called anamnesis and epiclesis) were done by one of the Jesuit priests, Father Siegmund Laschenski (if I remember correctly). Holy Communion was celebrated at two tables side by side, symbolizing our lamentable separation, we said. We later found out this was a historic and not uncontroversial thing we had done. The Vatican newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano had a front page note that asked simply, “What have the Jesuits in Chiang Mai done?” That, Fr. Gomaine told us, was a serious reprimand, but nothing came of it. As 1968 approached it was the Protestants’ turn to host the event. This time we proposed to have the Roman Catholics insert a short original cantata into the liturgy which would be conducted in two locations. The first was to be in Sacred Heart Cathedral recently finished as a gift from the King of Belgium. Gerald Dyck of the Thailand Theological Seminary’s Department of Church Music wanted to compose a cantata in the style of JS Bach, with solos, arias and choruses. He asked me to write verses for the choruses. It was accompanied, as Gerry remembers it, by a string quartet. Singers and musicians from both the cathedral community and from First Thai Church practiced and performed. The cantata was suitably focused on Peter’s confession that Jesus was the Christ, and the response, “You are the rock on which I will build my church.” Gerry took the cantata to Bangkok where he put together a larger ensemble (at a rehearsal of which the photo above was taken, from Gerry’s memoirs). From 1969 on, the joint services were organized by the two large Chiang Mai congregations rather than the student centers. Services are held in Bangkok to the present time. Predictions are largely projections of our hopes and fears, a friend of mine has reminded me. He’s right that they are largely projections, but I believe my predictions for 2019 are also observations based on evidence and experience interpreting trends I know something about. For what they are worth, here are my SIX GRIM PREDICTIONS FOR 2019.

1. The coronation of the King of Thailand on May 4-6, together with national elections and the ratification of a new constitution will consolidate the power of the military-royal alliance. It will give the King the most power a king has had in Thailand in nearly a century, since the end of the absolute monarchy. Some scholars say this is a virtual restoration of the sort of power once vested in the monarchy backed by an army under his personal control. 2. The US government will enter a time of crisis recalling the debacles of Nixon-Watergate, Warren G. Harding-Teapot Dome bribery scandal, and Andrew Johnson’s 1868 impeachment trial decided by a single vote by the junior senator from Johnson’s home state of Tennessee. Donald Trump is losing support he needs to stay on top. His plan in becoming President was to amass a personal fortune, and the GOP’s plan in boosting him was to erase as much government interference in big business as possible. They were counting on rapid action (especially Supreme Court appointments) before the great majority gets its counter-action coordinated. Time is running out on Trump and his dwindling backers. Trump is speeding up the clock by his bizarre antics and his public attacks on his critics, even those within his own inner circle. 3. It is really just abortion that holds the Christian Right together as a nationalistic force in the USA. Without abortion the coalition between right-wing Protestants and Roman Catholics would dissolve. Behind all the rhetoric and flag-waving is the plan to make abortions a crime. But behind that is the millennia-long struggle to repress sex. Abortion, by itself alone, is a contest between those compelled by the emotional notion that innocent children are being slaughtered, and the analytical argument that aborted embryos and fetuses are not yet children in any rational sense. Emotion always wins in contests of this sort. But when the matter expands to include the whole array of sexual freedom, action swings back and forth. Abortion has been politicized, but the longer-term outcome depends on the pendulum more than the politicians. 2019 will feature a major re-eruption of abortion battles but the swing on the broader question is away from the radical right in Europe and America. 4. China will not overtake the USA as the world’s major money merchant … this year. However, the USA has misplayed its hand too many times to recover. When China gains control, the blow to the US standard of living will be astounding. Of the great income producers (mining, manufacturing, and marketing), marketing is the easiest. Of the things to market, as the merchants of Venice discovered, money is the easiest – and banks are the money markets. My grim prediction for 2019 is that the USA will pass a tipping point from which it will not recover. This may not be the onset of another economic depression, but it could be a big policy blunder such as letting the national debt escalate to the point that borrowers of US dollars disappear and creditors begin to collect US gold, or failure (again) to hold financial magnates accountable at some critical juncture. 5. As for Christianity, 2019 will bring still more shift from the northern to the southern hemisphere. Euro-American hegemony of world-wide Christianity is at an end. The Pope is from South America, African Anglicans can compel the Anglican-Episcopal alliance to do what it wants, at least on some issues. Christianity has chosen sex and gender as its special target and has backed cultural repression of LGBT people, as well as outright persecution and prosecution. The few Christian groups and denominations that have resisted have been fractured, and are failing to stem waves of disenchantment with organized religion north of the equator. In 2019 the United Methodist Church will have its turn. It will be the year they make the choice of which side to take. In fact, a General Conference has been called for February 23-36 in St Louis to consider “human sexuality” and coincidentally whether to tolerate threats from Methodists from the southern hemisphere. 6. Higher education is in jeopardy. Its value measured in terms of “cost v. worth” is questionable. Already, valuable alternatives are developing as employment opportunities for graduates shrink. Here in Thailand the vast majority of college and university graduates do not retain positions more than five years related to their undergraduate fields of study. The exceptions may be health sciences and engineering. And even those who do work at jobs for which their degrees prepared them, have positions for which they could have been trained more quickly and cheaply than by university education. The more higher education becomes about training skilled workers for service positions so they can be factors of production, the less higher education will be thought to be necessary. In the USA a rebellion is developing against the modern indentured servitude that immense, career-long student debt imposes on students who now find jobs in their field are low-paying or unavailable. For decades the goal of higher education was the production of a valuable national human resource pool of independent thinkers. Today, not only is independent thinking considered unnecessary, it has been rendered largely impossible by post-modernism wherein the voice of the individual is indistinguishable from the voice of the group. In Thailand the problem is exacerbated by the unmitigated over-supply of university “seats” available due to unremitting construction of universities and falling birthrates (6.2 children per mother in the 1960s down to 1.5 in 2017). Last year there were 300,000 seats available for which just 230,000 students applied. The number of students at private universities in Thailand is down by 70% nation-wide. This decade, 2016-2026, will see accelerated decline of the perceived importance of higher education compared to expanded options, just as the half century, 1966-2016, saw a devaluation of education so that a bachelor’s degree acquires for graduates what a high school diploma used to provide. 2019 will see several closures or mergers of high-profile institutions of higher education. I commit these 6 grim predictions to print so they can be reviewed this time next year. I rest my prophetic reputation on them. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed