|

The emancipation of Thai slaves in 1905 was initially a very unpopular edict, especially among the slaves themselves in Lanna, the northern region of Thailand and adjoining principalities. This inconvenient fact is never explained in textbooks and is being gradually obliterated from the national narrative for a number of reasons.

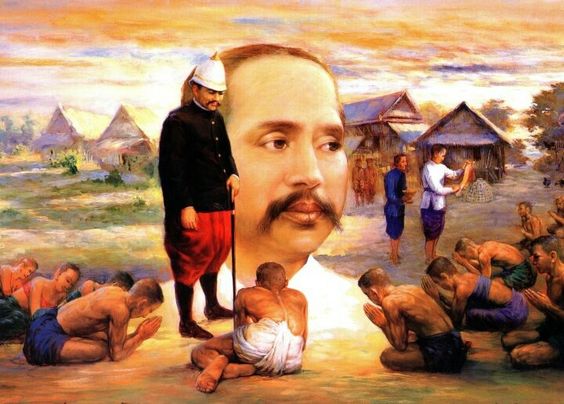

1. The standard narrative exalts the King of Thailand for doing away with slavery as it was being eliminated by his contemporaries in Europe and the Americas. The ending of slavery was a glittering example of his benevolent enlightenment and modernization. 2. It is unpopular after several decades to remember that the inclusion of the Lanna Kingdom into the Empire of Siam involved extensive cultural suppression and shifts of power into the hands of the Bangkok elite. 3. The most potent resistance to the centralization of authority came from exalted Buddhist religious leaders. This remains marginally true today in the North, and even more so in the Isan (Northeastern ethnic) region. The official account of the freeing of slaves in Siam makes several points. (A) In the beginning of the reign of HM King Chulalongkorn in 1868 “more than 1/3 of the population were slaves” due to the fact that “it was so because there was the endless continuity of offspring slaves. They all were slaves for the rest lives. Traditionally children of slaves also became slaves.” (B) In 1900 it was decreed that slaves had to be given pay or credited for their labor at a fixed rate, the children of slaves were freed at age 21, and the value of a slave was fixed (a boy was worth about 10 baht and a girl was 8), but the enslavement was actually based on the amount of money owed to a creditor and repayment was established at the rate of not less than 1 baht a month. (C) In 1905, Royal Edict 124 “Slave Act” declared the end of the sale and resale of slaves. Reality was a bit more complicated. There were basically three kinds of slaves in 18th and 19th century Siam, and throughout the region. One kind was those who had been conquered in war. They were forcibly relocated to reduce their ability to continue opposing the victors. They also had certain valuable skills that were appropriated. At one time, for example, the village of Hang Dong, immediately Southwest of Chiang Mai, was a place where slaves from North Burma were resettled. They were considered valuable because they were paper-makers. They were exempted from corvee labor pools and other taxation, since they were “slaves”. In other words, their slave status was beneficial, and was resented by previous residents who were displaced and less privileged. This separate status from centuries ago still has influence in local politics today. The second kind of slaves were called money slaves, actually คนเงิน ”money-people” and not that “slaves”. They were debtors who had defaulted on their debts and were working off their indebtedness. They had used their own person as collateral. Although they could be indebted to wealthy patrons, it was temples in the north that were the biggest money-lenders. Therefore, temples had the largest number of these slaves. Historian Hans Penth puts this type of slavery into perspective. “Monasteries and their accumulated treasure served as banks: a person could borrow money from a monastery. Upon default he or she became a so-called money-slave … of the monastery until the debt was cleared. Being a monastery slave was better than a tax shelter: the person was exempt from taxes and also from corvee labor.” (Penth, Hans. A Brief History of Lan Na. Chiang Mai, silkworm Books, 2008. P. 118.) Being a slave offered significant protection and generally no greater travail than other serfs endured. A third kind of slavery, Penth reports, is “honorary slavery,” “those who freely attached themselves to a certain monastery or holy place and pledged to take care of a certain part or a certain building or Buddha image, which was considered an honor. Important monasteries would have more than a hundred of these honorary slaves.” (Penth, p. 118). All these kinds of slavery gradually ended, but not gladly. “Many of these changes were bitterly resented and even opposed, not only in Lan Na. The time-honored bondman or serf system (in the West usually called a slave system though these slaves were generally well treated, in particular in Lan Na) was an accepted social and religious institution. … With the gradual abolishment of the system the creditor felt that now he had to pay wages to a person who actually owed him money. Also for hundreds of years it had been a very meritorious act to forsake the service of one’s bondman and to present him to a Buddha image in a monastery, so he could serve the image. This great source of making merit was now closed.” (Penth, pp. 137, 138). The King’s enlightened benevolence and role as “beloved father of the nation” has to be seen also in the context of his political struggle to consolidate power in order to present a formidable resistance to British and French colonizers. His internal adversaries were powerful clans and vassal princes whose authority and power were derived from serfdom and economic slavery. What the King was doing was to undermine the economic foundation of the system that supported opposition to centralization of power. His attack was twofold. In addition to the elimination of using persons as collateral to secure loans, the King decreed the right of ownership of land throughout the empire to the people who actually farmed the land. Area princes were no longer land-lords and masters with life-and-death authority over the people under his (or sometimes her) sovereignty. This infringement of rights was offset by two major changes in the way Siam ran. People could no longer use their persons as collateral to acquire loans, but they could use their land as collateral. The former landlords could no longer derive income from the labor of the serfs, but they could become honored employees of the King as a whole new bureaucracy was developed to oversee the country and expand its agriculture and manufacturing, as well as centralized banking. When this shift became fully in effect, a large amount of the dissatisfaction with the end of slavery was reduced. By the 1930s, the only major resentment was on the part of religious institutions. After centuries people could no longer make great merit by turning over slaves or by becoming a slave attached to a Buddha image or temple precinct. What’s more, the entire Sangha hierarchy was being subjugated to central control under the King. Leading monks have resisted this, and continue to be the single most powerful bloc to unrestrained power by the military-royalist alliance.

1 Comment

Tony Waters

1/28/2019 05:37:56 pm

Great summeary . Something new to talk over at lunch sometime! Are you ever on campus?

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed