|

REMINISCENCES

It’s commencement season. Virtually every institution of higher education on earth is having a ceremony to send graduates into the big world. Celebrity commencement speakers are competing for sound-bites but tend to be out-shouted by candidates for political office this year. Were I to be a commencement speaker (a role I used to fantasize might happen, but now never will), I would lament the demise of liberal arts. Liberal arts have declined – declined so far, in fact, that I feel constrained to explain what I am talking about. “Liberal arts” is not a course of study, but an approach to higher education based on the idea that a college graduate would be a leader in society by virtue of an elite educational background. The first question was, “What academic equipment does a leader need for the multiple tasks to be faced?” It was assumed that a college graduate would be a professional, but also more. A dentist might be on the school board, a governor’s committee, or even the governor. A librarian would be counselor to most people in town. A medical doctor might not only be on the hospital board, but the city council, the church council, and the draft board. A physician who became a missionary was ipso facto also a theologian, linguist and anthropologist. A community leader would need to draw on a wide range of knowledge, or at least not feel like an alien when a discussion was going on about something from literature, history or natural science. It was important for the intellectual area of life to be as familiar as the social circles of the community would be. The task of tertiary education was to acquire a well-rounded understanding of how life functions for the optimal benefit of everybody. Embedded in education was the concept that “ethics is the ability to think critically about life processes and morality is living in conformity to ethics”. These were to be learned if one was to be a leader. When I went to college in 1958 I was certain it was a step toward seminary and that was preparation for a lifetime of pastoral ministry. I thought I’d have a role in town equivalent to a school principle, chief of police, and superintendant of the hospital. But first I came to Thailand with the same intent I had in college: to be more well-rounded and informed as I prepared myself to contribute to a better society and world. About the time I was hitting my stride as a pastor-professional, I heard a warning, “Middle age is when you expect to begin to collect your rewards for playing by the rules, and that’s when they change the rules.” The big shift in our case was into a corporate mentality. The mayor of our town was no longer a citizen presiding at city council meetings, but was the CEO of the civic administration. Leaders were specialists, not generalists. The idea of a leadership elite with a holistic vision for society was eclipsed by searches for managerial specialists who would do their job and keep out of the way of other experts doing their jobs. I am not lamenting my loss of opportunity to wield civic responsibility. I did think Sam Harris, from the town where we lived, President of the Illinois Senate, might nominate me for a position on a state committee … but nevermind. I returned to Thailand just in time to join my friend from college days, Dr. Amnuay Tapingkae, waging a battle against the national higher education bureaucracy to develop Payap into a liberal arts college. We got there too late and in the wrong place. By the 1980s, what Thailand insisted was needed were trained employees. A college graduate was to become part of a corporation of some sort. Some corporations were called companies, some were professional associations, or government organizations – they were functionally corporations. Higher education had become the human resource production tool for corporations, and corporations began to take over what the university taught and then also how universities operated and were oriented. Corporate mergers and internationalization made the world more complex and opaque. Massification of higher education eliminated the status of graduates as elite. A bachelor’s degree now certifies that one is merely qualified to begin to undertake specialization or professionalization, or licensed to search for employment as one still unqualified. Ironically, the bulk of undergraduate work is increasingly supposed to be vocational, answering “how” without questioning “why”. In order to get into a success track, there is a selection process that gives priority to those with demonstrated capacity to excel, meaning that by graduation from college a student would have to already be “excellent”. Pre-professional bachelor’s degrees like the pre-theology program I took, or pre-med and pre-law, were narrowed so that a graduate entered professional graduate school having already taken as many profession-focused courses as possible. The need to show excellence has also driven the bell-shaped grading curve lopsided. Now students will not stand for grades below outstanding or excellent. Grade inflation is so rampant that grades no longer are treated as indicators of real achievement. Meanwhile, there is no time in undergraduate programs for becoming liberally educated and well-rounded. “Humane letters” is an archaic term. Education for appreciating areas of life (arts, literature, languages, philosophy, and culture) has become a luxury that is both too expensive and too time-consuming. As expected, we now have a couple of generations of people who are very selective in what they appreciate, and tend to be unwilling to appreciate people who appreciate other things. I was expounding on a type of literature the other day and was interrupted, “You misunderstand that I care!” I had misunderstood that, but it reminded me that it can no longer be assumed that people care about each other very much either. When this becomes instilled in society (and I believe it has already been) conflicted values and intolerance are sure to follow. A culture without arts is impossible. But a culture that no longer knows what arts are is one in an accelerated rate of decline. There is more at stake than the loss of a well-rounded leadership class. The loss of liberal arts is the loss of comprehensive education, sabotaged in order to produce trained workers who need not aspire to leadership nor be concerned about what their leaders are doing. PS-This 2014 article from Psychology Today "The Cult of Ignorance in the United States" expands on the underlying points of this week's blog.

0 Comments

REMINISCENCES

Thailand Theological Seminary as I first knew it in 1965 was a campus built around an imposing central building called either the Main Building or the Yellow Building ตึกหลวง or ตึกเหลือง . The building was constructed on a field in the Nong Seng village part of Chiang Mai Municipality across Kaewnawarat Road from the American Mission Hospital grounds. Both the seminary and the hospital, as well as Dara Academy for girls, were being moved from crowded locations along the Ping River. The cornerstone for the seminary was laid on 25 February 1914 by Mrs. Sophia Bradley McGilvary, wife of the late Rev. Dr. Daniel McGilvary who is credited with founding the evangelist training program that developed into a seminary for pastors and evangelists. At the time of its dedication in October 1915 it was the largest building of its type in Chiang Mai. Funds for the building were provided by the American Presbyterian Mission, which donated $3500 and Mrs. Louise Severance of Cleveland, Ohio who contributed $15,000. [$18,500 in 1915 is equivalent to $436,600 in 2015 funds or about 15 million Thai baht]. As I was introduced to the seminary, the 2 floors were divided, north and south. In the middle, on the ground floor behind the front doors was a reception area with dining area behind. Food preparation was done in a small building behind the dining area. Toilet buildings were there, too, used for storage since restrooms had been installed inside the main building. The ground floor to the north (to the left from the front door) was a hallway with the Rev. Prasert Intaphan’s office and the Rev. Francis Seely’s textbook project office. Beyond, were classrooms on the right and left. The ground floor to the south gave access to an academic office across from the seminary president’s office. Farther down the hall on the left were an apartment on the left and the chapel on the right. The second floor contained the library and study hall in the center with the women’s dorm to the left and offices and small classrooms on the right. By 1965 the campus contained several residences and a wooden dorm for men. The oldest house was a small bungalow east of the seminary building that had been built for Ajan Prasert and then housed the Koyama family until their new home was finished. That’s where I lived until 1969. The west end of the campus had a wooden house in which Drs Harold and Harriet Hanson and their 3 boys lived, a concrete house for Dr. John and Betsy Guyer (with Janet and Jimmy), and 2 houses built by Taylor Potter in which Dick and Estelle Carlson and 5 children lived next door to a similar house built for the Rev. Dr. E. John Hamlin and “Khun Fran”. The history of the seminary can be divided into 3 eras: pre-war, post-war, and Payap University. During the years before 1941 the seminary was an unofficial training center for church workers. During World War II when many Christian institutions were closed, the seminary building was used by the Japanese army as a hospital and morgue. This led to the tightly held conviction of students in later years that the seminary was haunted, and there were anecdotes to bolster that belief, despite protests to the contrary from the missionaries and somewhat weaker support from church leaders. Following the war, the seminary was rehabilitated and converted into the configuration I first remember. The Rev. Herbert Grether was assigned to re-open the pastoral training program as a full-fledged seminary. The Rev. Prasert Intaphan was his colleague in this endeavor. By the time I arrived, Dr. Hamlin had been recruited to preside at the seminary, and he undertook a bold up-grading and expansion of programs. By 1965 there were 5 identifiable units of the seminary. Pastoral training was a 7-year Bachelor of Divinity degree program, unauthorized by the Thai Ministry of Education, but accredited by the Association of Theological Education of South East Asia. The Christian Service Training Center was a development of the Marburger Mission, with a separate campus in Pa Kluay Village next to McKean Leprosy Institute; the CSTC was designed to provide bi-vocational pastors with employable skills as well as a basic theological education so they could be self-sufficient in small rural churches unable to pay a living salary. The CSTC academic program had been brought into the seminary by 1965. A Department of Christian Education was developed to train specialists in Christian religious education. A Department of Church Music was established to help improve the music and worship of churches. This department was transferred into Payap College as the college was founded in 1974 and is today the College of Music of Payap University. Finally, there was a Lay Training Institute that provided a sequence of summer courses for lay leaders, supposedly elders in churches, but usually the participants were young people. The staff and faculty were international: Hamlins from the USA, Riemers and 2 other couples from Germany, Koyamas from Japan and the USA, Suells from England (just leaving as I arrived), Ajan Prakai Nontawasee, Kamol Arayaprateep and Rev. Pisanu Arkkapin from Thailand, Manickams from India, Pouws from Indonesia, as well as Jane Arp, Kellys, Carlsons and Judds from the USA. There was a wide range of activities going on, including “field education” on weekends. Seminary students were all assigned to churches where they helped teach Sunday School, lead worship, conduct youth activities and sometimes serve as pastors in all but name. The churches around Chiang Mai counted on these seminary students, and the students benefitted from hands-on experience. In 1974, when Payap College was opened it was expected that McCormick School of Nursing and Midwifery and the McGilvary Theological Seminary (the new name by then) would be pillars of the college. Dr. Hamlin had been working for more than a decade to get the seminary degree fully recognized and that was now possible. However, seminary alumni and leadership of the Church of Christ in Thailand were concerned that the government would exercise control over course content and mandate secularization of theological perspectives. In 1979 the CCT consented to let the undergraduate programs of the seminary be part of Payap. The seminary was then called the McGilvary Faculty of Theology (today it is the McGilvary College of Divinity). Its B.A. program was 4 years, with the Master of Divinity program an additional 3 years, as is standard around the world. The Thai government still does not officially endorse the M.Div. degree, but it is accredited by ATESEA as it has been. The CSTC program was phased out. The Christian Education program became a department of the seminary. And the Church Music program split into a separate department of church music for seminary students offering tutorials and a couple of credit courses, while a much larger program in music developed in the Faculty of Humanities and then became the Faculty of Music, now the College of Music. In 1989 the old seminary building was torn down. The small street behind the seminary had been expanded into a 4 lane modern street placing the back door of the seminary almost in the street. Plaster and stucco needed replacement and the building was subject to termites. So on November 1, 1989, the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the seminary programs, the old building was de-commissioned and the “foundation stone” for a new building was ceremoniously blessed. May 14, 1965 was a memorable day for me, but not primarily because it was my 25th birthday. That was the day I graduated from McCormick Theological Seminary and ended 19 years of continuous formal education. The hymn that ran through my head that day included the words, “Time like an ever-flowing stream, bears all its sons away. They fly forgotten as the night flies at the break of day.” I was very conscious of soon flying away from Illinois for distant Thailand, although I thought it was to be a brief tour away.

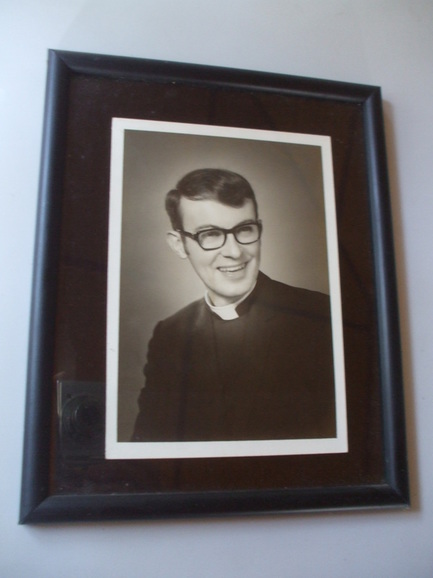

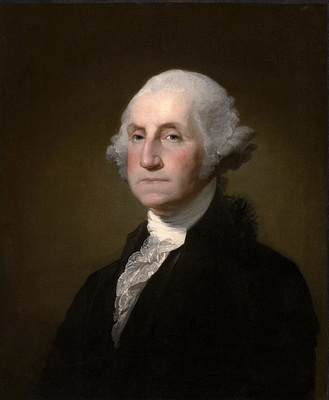

Now, rather than reminisce on a comparison between past and present which a person my age is wont to do, I want to ruminate on what I have observed that cannot be learned through comparing experiences. It’s hot today, very hot. People say it’s the hottest stretch of unbroken high temperatures Thailand has had in more than 6 decades. But it is not proof of global warming. Climate change is a matter of centuries. Warming is calculated by thousands of temperature measurements from all over the world averaged month by month. Local extremes count for little. But the totals count for a lot. Two degrees rise in worldwide averages will show up in major ice melts, higher sea levels and coastal erosion. That has nothing much to do with “more tornadoes”, “less rainfall” or any other weather trend we think we might have discerned. I’m a member of two national cultures. Both of these cultures are experiencing political dissonance. How else do you explain people’s relative apathy toward what’s going on at the political top of the two countries you know I’m talking about? But it’s not proof of intellectual decline. Even if educational systems’ failures have had some impact on people’s disinclination to do critical thinking, the willingness to go along with avalanches of absurdity is too profound to be the fault of schools alone. Comparisons do not help us get to the bottom of this. We cannot explain Trump by comparing the amount of homework American students have, compared to students in Finland. It doesn’t help to compare political indoctrination and intimidation in Thailand with North Korea. The dissonance between people’s values and life goals and their placid reaction to what’s going on is too vast and systemic to be the fault of some isolated thing that can be easily remembered and compared. “You are high church,” a seminary classmate noted in May 1965. My ordination picture that month (above) is pretty clear about that. I did not disagree, since I understood “high church” to mean I trusted the institutional church to promote what is best for humankind, and to take appropriate corrective action when ecclesiastical change is needed. It was this ideal sort of institution that I felt committed to help lead. I am older and disabused of that idealism now. But it is not my disappointments and experiences that have convinced me that institutional religion is at a threshold. In fact, I tend to believe that institutional Buddhism is about to have a metamorphosis and institutional Islam is splintering even as Islam grows. What is developing and spreading is spiritual diversity, focused on a narrow range of personal attractions to particular objectives, leaving people free to sample and move around. There are Jewish Buddhists in Brooklyn and Chiang Mai, Hindu Catholics in Toronto and Mumbai, atheist Unitarians in Boston and Bangkok. We would be mistaken to see this as a post-modern phenomenon. It has been coming for 500 years and it is just beginning to take a new form. The conclusion of this set of ruminations on my natal anniversary is that there are truths based on evidence too extensive for us to validate or disregard from our own experience. But we can decide to include the best informed conclusions on these things in how we do things. What we cannot conclude is that our actions do not matter. Tonight we may be gone and tomorrow forgotten, but our carbon imprint will linger. Every year at Pesach (widely called Passover in English) many Jewish congregations in the United States read a letter written by George Washington, sent on August 21, 1790 to Jews in Newport, Rhode Island. The impact of the letter was to state clearly Washington’s support for the concept of utter separation of religion from government. In the letter to Jews in Newport, Washington goes beyond the prevailing notion of Patrick Henry and others that the US is a Christian nation and that other religions may co-exist at the behest of Christians. The free exercise of religion is a “natural right” Washington argued. It is inherent in the nature of things, a human right not subject to being bestowed although it can be protected. Toleration of religious minorities anywhere in the United States is not a prerogative of the majority, but is an inherent right of all classes of people. The US was to be a pluralistic society.

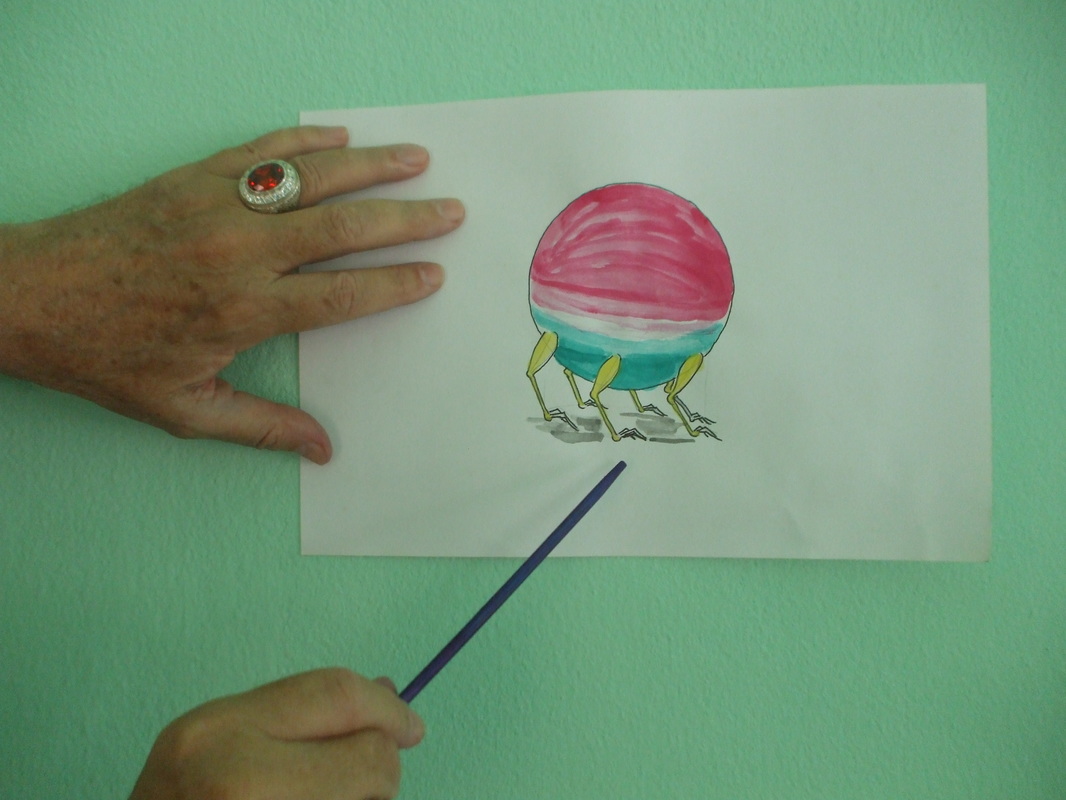

Washington wrote: It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support. The principle was at the very heart of United States’ independence. The issue was from whence come human rights. The Revolutionary War was fought over this very principle, with the US Patriots insisting that certain rights are “inalienable”, “self-evident”, natural, inherent and universal. Moreover, those who govern, do so by the will of the people at the grass roots. Then those rights were enumerated, including “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” The British resisted, arguing that rights are bestowed from above by those who have divine authority to govern those below them, class by class; otherwise there is social chaos. Shortly after the Revolutionary War was won (temporarily, to be continued in 1812) and the US Constitution was drafted, it became clear that the “rights” claimed in principle in the Declaration of Independence needed to be more carefully enumerated in the Constitution, so ten amendments were attached to spell out these rights. A key (and the most contentious) article stated, “Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” This was article three in the draft of 1789, but since articles one and two were not ratified, it became Amendment I in the version ratified by 3/4ths of the States as of December 15, 1791. Subsequently even this was clarified to mean that states also have no authority to make laws establishing a religion or prohibiting the free exercise of religion. Washington’s letter and several other letters he wrote and speeches he made in 1790 and 91 were on the anti-establishment side of the debate. He was honored and thanked by religious minority groups for his support. Those groups included Jews, Muslims, Quakers, Presbyterians and others being or feeling threatened by religious establishments in various states. Some of those states included ones founded in order to provide religious freedom, which generally meant, “freedom for us to practice our religion.” Groups practicing other religions were not always welcome. Washington and his like-minded revolutionaries felt that the only solution was to separate the functions of church and state. In due time the principle was accepted that no churches or religions were to be established by state or federal governments and those already established were to be dis-established. Thenceforth, there would be no Puritan Church established by Massachusetts, no Episcopal Church established by Virginia, nor a Mormon Church governing Utah, a Roman Catholic Church as a state function in Florida, Texas or Maryland. On the other hand, no state or federal agency would have authority to limit or interfere with people undertaking religious practices that did not deprive other people of their human rights. It is a measure of how much this two-century-long consensus has deteriorated, that presently the debate is back to whether the USA ought to declare itself a Christian nation and thereby relegate other religions to the status of “tolerated” rather than entitled by inalienable natural rights to practice their religion. As George Washington understood, we cannot have it both ways. Either religion is an inalienable right or it is not. The intervention of political government into the direct connection of human beings to God is never other than the re-establishment of a Church-state, no matter what it is called. Professor Virgil Verbal’s classroom in Hogwarts castle was a semi-circular shape which was useful in many ways. In the first place, from time to time the students sat in two or three rows facing the center where something was going on. Professor Verbal rarely lectured, but often read aloud and sometimes acted or performed. More frequently groups of students did that. Some of the time the students were involved in composing ideas, which was the way the professor referred to writing. “It is much more than writing, don’t you see,” he would say. “The writing is the part that happens when the ideas are trying to escape. You capture them with your sharp pens while they’re still squirming around in your head. They can’t get away as easily when they’re all spread out in view.”

“Oh yes,” Professor Verbal said enthusiastically one day, “language is quite as magical as any hex or charm.” The students laughed at this absurd idea. “Come, come, don’t make it so hard for yourselves,” Professor Verbal came back at them. “You can all learn how to make words turn into images or ideas. Some of you are quite good at using language to draw attention toward something you want people to notice.” The students chortled again. “Oh, indeed! Just a few well chosen words can send minds racing far away, or re-create a time and place that once existed or conjure one up that never existed at all. With words you can make people think or forget. You can have the power of the dream spinner.” “But dreams aren’t real,” a student objected. “Whatever gave you that idea?” Professor Verbal responded. “Well, when you wake up the thing you dreamed is gone,” another student picked up the challenge. “So it’s all in your head.” “Oh, you mean that a thing is not real if it does not exist somewhere else as well as in your mind. I think a thing might be quite real even if it were only a dream-like thing. Let’s try an experiment,” Professor Verbal said, as if he were making a suggestion rather than uttering an imperative. “With words alone, I will describe something and we will see what we can see with just what’s in your head, without anything ever going first through your eyes.” Professor Verbal got a far-away look in his eyes and began, “I-bows are about the size of watermelons but quite round like basketballs. They are pink on the top and green underneath, green as a mint leaf. Each of the I-bows has six legs, like the legs of a bird, with three toes on each foot. The legs are evenly spaced all around and the three toes on the feet face in the direction the I-bows want to go. There are no other things visible, no eyes or tails, for instance.” Professor Verbal then took a deep breath and finished, “Now, draw a picture of an I-bow.” When the pictures of the thirty students were finished Professor Verbal posted them all around the outer wall. As the students walked around admiring the work and comparing each other’s pictures to their own, Professor Verbal spoke to them. “That is the magic of language. Nobody has ever seen an I-bow but you could all draw a picture of one. What’s more, almost all your I-bows are so much alike that if a person knows what one I-bow looks like they’ll know that something else that looks like that is an I-bow. Shall we give it a try?” Matching his actions to his words he went to the door and called in two students who happened to be in the hall. The teacher held one of the pictures in his hand. “This is an I-bow,” he said and then repeated it, “an I-bow.” Then he gestured toward the pictures on the wall. “What are those?” The two students looked back and forth between Professor Verbal and the pictures as if they were hoping for some clarifying reason for this quiz or perhaps an inspiration, but after a little while both students surrendered. “They are I-bows?” they said with their voices going up as if they were trying to straddle the line between an indicative and an interrogative statement. “Yes,” Professor Verbal nodded sagely, “if one of them is an I-bow, it would be reasonable to conclude that all these splendid portraits are of I-bows. Would you be surprised to learn that no one has ever seen an I-bow before this very hour?” Professor Verbal asked the two visitors who were smiling faintly and edging toward the door without answering. “Well, thank you for confirming our discovery.” When the two visitors had gone Professor Verbal turned again to the class. “So you see, it is not necessary for a thing to exist anywhere outside our mind for it to be real enough for all of us to have a fairly large consensus about it – as long as there is language to make the necessary connections. That’s the magic of language. “Now, would you say that an I-bow is more real than a penguin?” he asked, smiling good naturedly. “Less real,” several students assured him. “Well, let’s put it to a test. How many of you have ever drawn a picture of a penguin?” A few hands went up. “Not as many as have drawn a picture of an I-bow,” he observed without bothering to count the hands. “But maybe your having drawn a picture of something is not the only test or even a valid test of something’s existence. How many of you have drawn a picture of my grandmother?” the professor asked. No hands were raised, but a titter went around the room. “So we can agree that some things, perhaps most things in the world, are or were very real even though you cannot draw a picture or even take a photograph of them. Is the problem because of your artistic or technical skill?” “We don’t know what your grandmother looked like,” a student protested. “Well, let’s say that’s because I haven’t described her to you. We haven’t had the words.” “We could do better from a picture than your telling us,” one student challenged him. “Well, I happen to have a picture of her,” Professor Verbal conceded. A few seconds later it was being projected onto the front wall which served as a screen. “Confucius is said to have said that a picture is worth ten-thousand words. Let’s try that out.” Verbal drew a card from his pocket and held it up beside the picture of his grandmother. They were the same size. “The card has about a fiftieth of ten-thousand words. Listen. “Lottie was born in a shepherd’s cabin in the highlands of Scotland where the birds taught her to sing, she said, and the sheep and her father taught her everything else that was important. The most crucial day in her life was in the winter when she was ten. There was a highlands blizzard and her father was lost in it. There was no food in the hut and the fire burned out. It would have been death to go away from the hut, but it was deathly cold inside. Toward evening Lottie heard some bleating. A few sheep had wandered up to the sheltered side of the cabin. Among the sounds outside she recognized the high-pitched stutter of a little lamb. ‘It’ll freeze,’ she told herself and she decided to rescue it. The lamb was easy enough to find, but its mother was not about to let the girl take it away from her. ‘Well, inta th’ cabin wi’ye,’ Lottie said. Before she could get the door shut there were seven sheep in there. After a while, their bodies warmed the room a wee bit and so they survived the last full day of the storm until Lottie’s uncles could get to her.” “Which tells more about my grandmother, the photograph or the two-hundred-word story?” Professor Verbal asked. Some students were sure the right answer was the story. “But why is the story a better look into my grandmother’s life than the photograph?” “It tells more, the story does.” “Does it tell us what she looked like?” “No.” “Well what does the story tell us?” “How she stayed alive and kept the lamb alive.” “What else?” “That she cared about animals. That they would come to her. That she didn’t panic and run.” “So is that what you’ll remember from the story, that Lottie was courageous, compassionate and lucky?” “Yes,” some agreed. “I doubt it,” Professor Verbal shook his head. “No,” Anthony admitted, “I’ll remember the little girl in the hut with the sheep keeping warm in the blizzard.” “Ah, the thing you’ll remember is a scene you can picture, a key part of the story. The picture in your mind is what will help you recall the abstract parts of the story, but the story is more vivid and informative than the photograph we saw. “One last thing about the power of language: why does it have power? Think about what you do when you listen to a story you are very interested in. Your ears take in the sounds and your mind makes connections with things you have stored in there. Lottie, sheep, cabin, blizzard. Notions of what these may be like are pulled into your conscious mind which is very busy as you quietly listen. You are in a very active frame of mind when you have to conjure up the pictures to fill in the blanks. It is easier to listen to a description when there are things to compare it to. I-bows are round like basket balls, the size of watermelons, with three-toed feet on legs like birds. You can picture an I-bow by assembling those parts in your mind. Your mind is very busy. “But what happens when you see a movie? What does your mind have to do? If the movie is like most of them your mind doesn’t have time to do anything but receive the images. The picture is full and your mind has to absorb what is given to it. The less it flits around the better, because you can absorb more. You must be passive. “Language is the most magical art form, students, very magical.” Professor Verbal straightened up and waved his wand so that the pictures of the I-bows flew off the wall back to their artists. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed