|

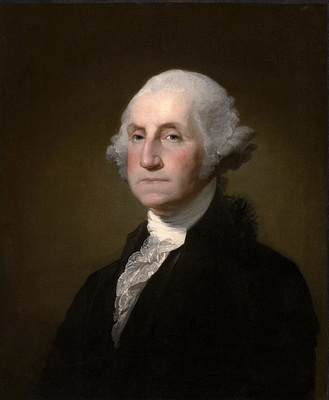

Every year at Pesach (widely called Passover in English) many Jewish congregations in the United States read a letter written by George Washington, sent on August 21, 1790 to Jews in Newport, Rhode Island. The impact of the letter was to state clearly Washington’s support for the concept of utter separation of religion from government. In the letter to Jews in Newport, Washington goes beyond the prevailing notion of Patrick Henry and others that the US is a Christian nation and that other religions may co-exist at the behest of Christians. The free exercise of religion is a “natural right” Washington argued. It is inherent in the nature of things, a human right not subject to being bestowed although it can be protected. Toleration of religious minorities anywhere in the United States is not a prerogative of the majority, but is an inherent right of all classes of people. The US was to be a pluralistic society.

Washington wrote: It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support. The principle was at the very heart of United States’ independence. The issue was from whence come human rights. The Revolutionary War was fought over this very principle, with the US Patriots insisting that certain rights are “inalienable”, “self-evident”, natural, inherent and universal. Moreover, those who govern, do so by the will of the people at the grass roots. Then those rights were enumerated, including “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” The British resisted, arguing that rights are bestowed from above by those who have divine authority to govern those below them, class by class; otherwise there is social chaos. Shortly after the Revolutionary War was won (temporarily, to be continued in 1812) and the US Constitution was drafted, it became clear that the “rights” claimed in principle in the Declaration of Independence needed to be more carefully enumerated in the Constitution, so ten amendments were attached to spell out these rights. A key (and the most contentious) article stated, “Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” This was article three in the draft of 1789, but since articles one and two were not ratified, it became Amendment I in the version ratified by 3/4ths of the States as of December 15, 1791. Subsequently even this was clarified to mean that states also have no authority to make laws establishing a religion or prohibiting the free exercise of religion. Washington’s letter and several other letters he wrote and speeches he made in 1790 and 91 were on the anti-establishment side of the debate. He was honored and thanked by religious minority groups for his support. Those groups included Jews, Muslims, Quakers, Presbyterians and others being or feeling threatened by religious establishments in various states. Some of those states included ones founded in order to provide religious freedom, which generally meant, “freedom for us to practice our religion.” Groups practicing other religions were not always welcome. Washington and his like-minded revolutionaries felt that the only solution was to separate the functions of church and state. In due time the principle was accepted that no churches or religions were to be established by state or federal governments and those already established were to be dis-established. Thenceforth, there would be no Puritan Church established by Massachusetts, no Episcopal Church established by Virginia, nor a Mormon Church governing Utah, a Roman Catholic Church as a state function in Florida, Texas or Maryland. On the other hand, no state or federal agency would have authority to limit or interfere with people undertaking religious practices that did not deprive other people of their human rights. It is a measure of how much this two-century-long consensus has deteriorated, that presently the debate is back to whether the USA ought to declare itself a Christian nation and thereby relegate other religions to the status of “tolerated” rather than entitled by inalienable natural rights to practice their religion. As George Washington understood, we cannot have it both ways. Either religion is an inalienable right or it is not. The intervention of political government into the direct connection of human beings to God is never other than the re-establishment of a Church-state, no matter what it is called.

1 Comment

5/8/2016 06:43:31 pm

Right on, Ken! You are this crucial point brilliantly: "It is a measure of how much this two-century-long consensus has deteriorated, that presently the debate is back to whether the USA ought to declare itself a Christian nation and thereby relegate other religions to the status of “tolerated” rather than entitled by inalienable natural rights to practice their religion. As George Washington understood, we cannot have it both ways. Either religion is an inalienable right or it is not. The intervention of political government into the direct connection of human beings to God is never other than the re-establishment of a Church-state, no matter what it is called."

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed