|

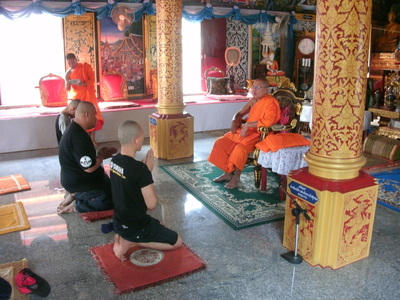

Ordination before the fire is a particular type of merit-making that is both fairly common and relatively undocumented. Buat naa fai could be called a cremation ordination and it is done by boys to make merit for a relative, often a grandparent. It typically is purely ceremonial in that the boys have no intention of remaining in the monastery community longer than one day.

This week’s blog is essentially a picture essay with concluding observations. First a few principles: (1) “Ordination before the Fire” is generally into novice status. (2) Since it has a particular, limited purpose there are few of the customary preparatory ceremonies such as formal leave-taking from mother and father, elaborate procession to the temple, or a feast for the chapter of monks and laity. (3) It is possible for the novice(s) to change their mind and remain in the temple longer than one day. (4) Not all abbots are willing to receive novices into this type of ordination. The elements of ordination before a cremation are simply the bare essentials for ordaining a novice into a temple community of monks. The pictures accompanying this blog are a record of 3 nephews who were ordained on March 25, 2016 to make merit for their grandmother, Mrs. Fong Wanna, in Sanpatong District, Chiang Mai, Thailand. The ordination included the following activities: 1. The boys had their hair cut and eyebrows shaved. This is normally done or finished by a monk, but in this instance the abbot told them to do this the night before the cremation. 2. On the morning of the cremation the boys went with older male relatives to the temple with the things necessary for the ordination. 3. The abbot presided, assisted by just 2 other priests. The boys ceremonially requested ordination and were asked the standard questions before being permitted to change into saffron colored robes. They left their street clothes at the temple. 4. They were then ordained by the abbot, who urged them to consider staying in the temple as novices longer than one day. 5. Down the street, preparations for the big funeral service were getting finished. The new novices drew everybody’s attention as they arrived with their assigned mentor. 6. The novices attended the chanting service, but participated as they would, had they still been laity. They sat off to the side. 7. When the chanting was finished everyone was served a community meal. The priests and novices were served first, and their food was specially presented. 8. As the casket was moved from the family home to the cremation grounds, the novices led the crowd under the direction of their mentor. The chapter of priests who had done the chanting and would preside at the cremation were taken by car. 9. The boys had a place of distinction at the cremation, but lined up with the family as all the guests filed past. 10. Following ignition of the cremation fire, which burned the catafalque spectacularly and the casket inside the cremation oven, the people left the cremation grounds. The priests returned to their various temples. The novices returned to the village temple where they quietly asked to demit and were given permission. They changed back into their shirts and jeans leaving their orange robes at the temple. Observations: This ceremony is all about making merit which is transferred to the deceased. It is a family-oriented thing to do. There is no intention that any of the benefits of regular ordination will accrue to the ordinands or the temple. The novices do not even have to memorize their ordination vows. They practice no meditation and only briefly adhere to any abstentions. The boys tended to feel self-conscious rather than honored. There was almost no time they felt at ease or knew exactly what to do. They were coached every step of the way. Their motive, in the end, was to express love and respect for their grandmother. This type of ordination is considered an optional custom, happening only in a small percentage of funerals. There is no stigma for foregoing this, even in large or prosperous families. However, having grandsons do this is a sign the family has “done everything possible” to see that Grandmother has a complete send-off. The very fact that this type of ceremony exists is sufficient to prove that merit-making is a valid part of Thai Buddhist practice. Furthermore, the merit is transferred in order to offset the demeritorious accumulation of the deceased, who is (of course) an entirely passive beneficiary. There are other ordinations to make merit in behalf of recipients. Sometimes there is even an elaborate merit-transferral ceremony. This has important implications for the theological understanding of karma, and functions in principle precisely as Christian atonement does.

0 Comments

Throughout the transitional era of Thailand from a basic economy and subsistence lifestyle into a progressive capitalist economy and middle-class lifestyle (1940-1990) the church undertook an amazing variety of approaches to supplement its three-fold mission with a fourth. Previously, Protestant work in Siam/Lao/Thailand had been directed toward improving life religiously, educationally and medically. Institutional supports for this were churches, schools and hospitals.

As Herb Swanson documented in Khrischak Muang Nua, his historical analysis of the Protestant Church in North Thailand, when threats from the Lanna authorities suppressed church growth among the Chiang Mai upper class, missionaries used their status as patrons to provide jobs for needy new Christians. The size and spread of the Protestant Church outgrew that strategy, and the missionary exodus from the north after Pearl Harbor brought it to an abrupt end. However, the impact of the “Social Gospel” and the scale of human needs of people after World War II in the church and within its sphere was so pressing that a new mission was undertaken: the improvement of people’s economic capacity. This impressive effort was in full swing when I arrived in Chiang Mai in 1965. There were as many agricultural and vocational missionaries as there were medical specialists, perhaps more. [Note: in 1965 and afterward as well, missionary wives were appointed by mission boards “to assist their husbands.” In fact, many of these women undertook an unlabeled specialized mission of vocational training and product development.] · American Baptist agricultural missionaries working with ethnic Karen Christians included Dick Mann, Rupert Nelson and Ben Dickerson. The efforts they showed me were about improved rice production and development of additional agricultural products including wool, fruit (grapefruit, passion fruit, apples) as well as coffee, tea and flowers. They also developed village water supplies, sanitary toilets, and schools. · American Presbyterian agricultural missionaries included Travaillers and Turnbulls at the Sampantakit Farm in Chiang Rai. The Farm was a cooperative experiment to homestead previously useless land into farms growing multiple crops and benefitting from united purchasing and marketing power. The goal was to demonstrate how previously landless peasants could become land owners with expendable income through modern farming methods including mechanization. Dr. Larry Judd undertook a broad effort in North Thailand to inspire and enable rural Christians (the great majority of CCT members at that time) to band together to improve their economic power. The CCT developed a Rural Life Department to coordinate these projects on a national scale. · Handicraft production and sales was another strategy that achieved international attention. Three enterprises were spearheaded by missionaries: Marian McAnallen’s Lao Song cloth products from Nakhon Pathom, Thai Tribal Crafts selling a wide range of hand-made items from ethnic villages in the northern hills, and handicrafts made by McKean leprosy patients and former McKean residents in satellite villages. The idea was that producers of marketable products did not need to be displaced from their homes and villages, nor taught new skills and trades, to make things that would bring in supplemental income. Marlene Mann, Dee Nelson, Idalene Conklin, Elaine Lewis, Dot Turnbull, Heather Smith, Marian McAnallen and others served as quality control coaches and “fusion” product designers. Key to the success of these ventures was finding markets for the products; Church World Service and the SERRV free-trade agency were the international outlets, expanding sales beyond shops in Thailand. In some cases handicraft production became lucrative enough that manufacturers gave up farming entirely. In 1965-70 McKean was a large, fully functioning village. Residents made furniture, did wood carving, custom printing and refined handicrafts, sewed garments, grew fruit, and raised fish and hogs. · An Urban-Industrial mission (following the vision developed by Dr. Marshal Scott at McCormick Theological Seminary) was begun in the Samut Prakan Eastern Seaboard area south east of Bangkok. This mission attempted to help displaced industrial workers cope with the challenges of slum-living, being educationally disadvantaged, and feeling powerless. Bryce Little helped the project get started and become an official unit of the CCT. The Rev. Somrit Wongsang and his wife, Nuansri, continued the work for another four decades. · The Marburger Mission undertook evangelism and church leadership development. An aspect of this included experiments in two fields: a diaconate program in which women committed themselves to a shared life of Christian piety and service, and a training program for “tent-making” ministry to equip men to be pastors with skills to generate a living at such things as livestock husbandry or motorcycle repair. One thing all these efforts had in common was an attempt to be realistic and practical about improving the living conditions of people mired in economic disadvantage. The basic reason they all faded is that they failed to help people achieve their real aspiration, which was to rise above their economic level rather than to simply be more comfortable within it. Yet for a while, these programs did generate hope and bring relief. Like strategies in H.M. the King’s “Sufficiency Economy Philosophy,” the church’s social-economic initiatives were interim solutions. It is unfair and irresponsible to accuse those who supported these efforts of surreptitiously trying to keep the lower classes servile and passive. I have read presumably responsible academic papers that made that charge. The projects did not fail if they helped people live better while rising above menial subsistence lifestyles and circumstances into the middle class. But the projects faded and folded when people born in the next two generations were able to “do better than that.” Prosperity comes in cycles, but for the present, the goal of village young people is to get salaried employment to escape the marginal jobs and unpredictable income of their agrarian parents and ancestors. These days, every family unit needs at least one person earning a salary. Income from a sideline such as handicraft production is not enough unless the manufacturing is on a full-time basis. Sidelines for farmers are in areas such as construction. For a growing number of villagers, however, it is farming that is the sideline. You do not know the name of God. No one does.

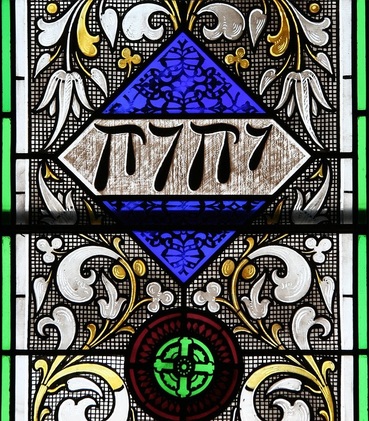

This is a universal theological truth, but this short essay is limited to a discussion of the name of the god who ambiguously said, “YHWH,” when asked for a name. Moses said to God, “If I come to the Israelites and say to them, ‘The God of your ancestors has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ what shall I say to them?” God said to Moses, “I AM WHO I AM.” He said further, “Thus you shall say to the Israelites ‘I AM has sent me to you.’ … This is my name forever, and this my title for all generations.” (Exodus 2:13-15, New Revised Standard Version) According to a recent article about YHWH, translating the phrase is difficult. That is in perfect agreement with my Old Testament professor several decades ago. For one thing, the letters can all be vowels (or vowel place holders) as well as consonants. Since the word (or phrase) was sacred it was unpronounceable, and without any idea how to pronounce it, it is virtually impossible to translate precisely. It can be rendered “I Am that I Am” or “I shall be what I shall be” “I shall be what I am” or “I will become what I will choose to become” or “I will become whatsoever I please” or perhaps (if the verb is causative) “Who causes to be” “Who gives life” or “Who causes to exist.” There are, I take it, only two possible reasons why God would tell Moses a name like that. It would have to have been in order to obfuscate and confuse, or to imply unfathomable holiness. You can guess which rationale I think is obvious. The outcome, however, was far from settled. Even though the god of the ancestors preferred to not to be on a first name basis, in a world of gods with famous names, Moses and a majority of his spiritual descendants didn’t think a nameless god would work out well. Beginning soon after the burning bush encounter in Exodus 2, Israelites coined and borrowed a large number of names which they used and often even enunciated when they came across YHWH in writing. Pious Jews, still later, hesitated to use any name for God. It became very confusing after all. At least the gender of God was clear from the beginning. Wasn’t it? Rabbi Mark Sameth submitted an opinion editorial to the New York Times in which he sought to correct our certainty about God as Father, He and Him. Rabbi Sameth says that YHWH was ambiguous not only with regard to tense (present or future) but also with regard to gender. In fact, the Hebrew Bible, when read in the original language offers a highly elastic view of gender. And I do mean highlyelastic: in Genesis 3:12, Eve is referred to as “he.” In Genesis 9:21, after the flood Noah repairs to “her” tent. Genesis 24:16 refers to Rebecca as a “young man.” And Genesis 1:27 refers to Adam as “them.” …In Esther 2:7, Mordecai is pictured as nursing his niece Esther. In a similar way, in Isaiah 49:23, the future kings of Israel are prophesied to be “nursing kings.” …In the ancient world, well-expressed gender fluidity was a mark of a civilized person. Such a person was considered more godlike. The idea of “nursing kings,” Sameth says, was derived from Hatshepsut who succeeded her husband Thutmose II and became one of Egypt’s greatest Pharaohs. That sets the stage for Sameth’s assertion that “the four-Hebrew-letter name of God … YHWH … would have [been] read … in reverse as Hu/Hi – in other words the hidden issue of God was Hebrew for “He/She.” In that ancient context, this would merely have been another way to indicate that God was too holy and remote to be too specific about. Sameth’s conclusion is, “…The God of Israel … was understood by its earliest worshipers to be a dual-gendered deity.” Now, having the benefit of 3000 years of cogitating on this, we have added several solid layers of certainty about God’s identity that earlier people would not have dared or dreamed of doing. Conveniently, it all fits neatly into our binary he-she social construct and rejects he/she as a possibility. Our refusal to look critically at our socially-biased belief probably wouldn’t matter if it weren’t being used as ammunition to slaughter each other in the name of the nameless god with many names. Fortunately, I learned from Rabbi Sameth, we do not need to object to the growing consensus about gender fluidity on Biblical grounds. HE/SHE was rather huffy about mortals being too inquisitive and adamant. Footnotes: Rabbi Mark Sameth’s article appeared August 12, 2016 in the New York Times. Downloaded: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/13/opinion/is-god-transgender.htmlwww.nytimes.com/2016/08/13/opinion/is-god-transgender.html A full discussion of YHWH can be found online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tetragrammaton “The Church of Christ in Thailand: Turning Into Its Own Idea”

The beginning of the Church of Christ in Thailand can be traced back to the missionary work of American Baptists and the Presbyterian Church in the USA, in the 1830s. The goal of both mission groups was to establish a church organization composed of local church congregations. The strategy was to identify and develop clusters of Christians with the potential of growing into self-sustaining, self-governing churches responding to critical needs for spiritual, educational and medical support. Projects to provide sustained economic assistance were added after the Second World War (and will be discussed in a later essay). In general, the Baptists concentrated on immigrant and ethnic minority groups while the Presbyterians tried to develop mission work with Siamese and Lao populations. Mission centers were built by the Presbyterians in larger towns including Bangkok, Petchaburi, Nakhon Sri Thammarat, Lampang, Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, Prae and Nan. By the end of the first missionary century, celebrated in 1928-29, there were Christian churches, hospitals and schools in each of those centers with satellite churches surrounding the larger centers. 1930-1980 was a half-century of refinement, expansion and transition. Mission work of the Christian Churches (Disciples of Christ), located largely in Nakhon Pathom and Ratchaburi provinces West of Bangkok, joined the CCT as District 11. Three types of entities developed separate missions: churches, institutions and organizations. These moved into various forms of autonomy or semi-independence. Churches tended to be self-supporting to the extent that they built and maintained their own buildings and larger churches hired clergy. The national Church of Christ in Thailand was formed. Schools and hospitals operated with fewer and fewer missionaries on staff and gradually none had missionaries as administrators. A couple of hospitals were closed as Thai government medical services expanded, but schools tended to keep going with new schools added from time to time either spearheaded by key leaders or as satellites or offshoots. Seminaries and other higher education institutions were established or “came into their own” during this era, including the Bangkok Student Christian Center and the Center for the Uplift of the Hill Tribes (now called the Siloam Center), followed by Payap University in Chiang Mai and Christian University of Thailand in Bangkok and Nakhon Pathom. Organizations that were neither churches nor institutions tended to be thought of as extraneous to the main mission of the CCT. They were treated in various ways. The Thai Student Christian Movement was tolerated rather than supported. Baptists developed a program in Chiang Mai for women (particularly women escaping from or avoiding prostitution) that, like the Bangkok Christian Guest House, is only loosely connected to the CCT. Sampantakit Farm cooperative in Chiang Rai “completed its mission” and dissolved, dividing assets among coop members. Free Burma Rangers never received CCT endorsement and is solely independent. The Voice of Peace chose not to join with the CCT. Whereas, the Klong Toey mission is fully integrated in the CCT but is required to operate as if it is not. These are examples. The list of organizations is extensive. Since 1980 (to pick an arbitrary date) the CCT has undergone major changes of perspective and operation. Although I am avoiding mentioning names in this essay, I need to mention two with regard to the way by which the CCT “turned into its own idea.” Khun Wibul Pattarathamat was a Thai-Chinese business man (some would say “tycoon”) when he was elected to a single term as Moderator of the CCT at the beginning of this third era. He installed a vision of financial independence that was controversial and daring at the time. His concept was that the CCT could operate on a business model utilizing resources at its disposal to make a great deal of money with which to run the church. Church real estate was one immense resource the church was underutilizing. Using vast property of the Foundation of the Church of Christ in Thailand Foundation as collateral, he pushed a plan to build a new church headquarters building on a piece of land behind the Bangkok Christian Hospital which included several floors of office rental space to produce income to pay off the loan and continue generating income for the church. He also implemented a self-development plan in 1979 for churches to use funds from the central church organization to pay pastor’s salaries in decreasing amounts over 10 years so that the congregations, with full-time pastors, would be able to grow large enough to be self-supporting from then on. This plan has been modified, but was the beginning of a major expansion of pastoral services across the denomination. The Rev. Dr. Boonratna Boayen served the CCT for about 30 years as Moderator or General Secretary. His vision was for the CCT to move from a level of chaotic decentralization and chronic dysfunction into a more centralized and tightly controlled national organization. Highly representative government was modified into a much more hierarchical form with power increasingly vested in top leadership, but units became more accountable and functioned more effectively according to stated plans than ever before. Revisions of the CCT constitution and book of regulations reduced the authority of boards of institutions and of church district councils (formerly called “presbyteries” then “districts”). Funding became centralized to the extent that the CCT top leadership team (the 9-member Executive Committee including the 4 full-time national church leaders) have the authority to intervene in any church or institution to review finances and replace board members and institutional heads, or even close institutions. The CCT has developed a very Thai way of operating, but has thrived at its main mission, which is maintenance of the CCT as an organization with functioning congregations. During this era virtually all 800 local churches have acquired full-time pastors (up from barely 20% in 1980), a majority of churches have built new church buildings or refurbished older ones to retain historical appearance. Since 1980 three large groups have been incorporated into the CCT: Christian churches in the Isan region (provinces in the NE section of the country), formerly established by the Christian and Missionary Alliance, joined the CCT as District 13. Karen Baptist and Lahu Baptist groups joined en masse, more than doubling the membership of the CCT. This influx motivated the second constitutional revision to insure that ethnic Thai and Thai-Chinese would retain control of the CCT. Major building programs since 1980 are beyond counting, but mention should be made of the CCT headquarters building in the commercial heart of Bangkok on the campus of the Student Christian Center, the Mae Kao Campus of Payap University, and the Nakhon Pathom campus of Christian University of Thailand, as well as 2 high-rise additions to Bangkok Christian Hospital. The CCT is no longer Presbyterian or Baptist. Some congregations retain aspects of their rites and heritage, but the whole church is more Thai than anything. There are no foreigners in the CCT administration or on national committees. The CCT has become what it sought to become, even as it grows on to become something else that is its own idea. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed