|

You do not know the name of God. No one does.

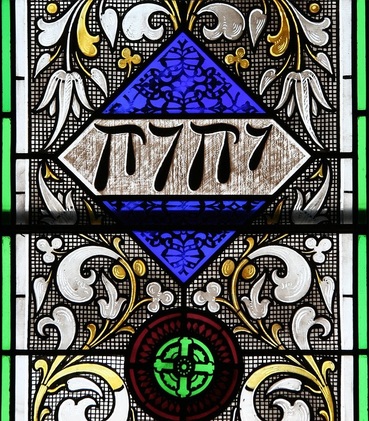

This is a universal theological truth, but this short essay is limited to a discussion of the name of the god who ambiguously said, “YHWH,” when asked for a name. Moses said to God, “If I come to the Israelites and say to them, ‘The God of your ancestors has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ what shall I say to them?” God said to Moses, “I AM WHO I AM.” He said further, “Thus you shall say to the Israelites ‘I AM has sent me to you.’ … This is my name forever, and this my title for all generations.” (Exodus 2:13-15, New Revised Standard Version) According to a recent article about YHWH, translating the phrase is difficult. That is in perfect agreement with my Old Testament professor several decades ago. For one thing, the letters can all be vowels (or vowel place holders) as well as consonants. Since the word (or phrase) was sacred it was unpronounceable, and without any idea how to pronounce it, it is virtually impossible to translate precisely. It can be rendered “I Am that I Am” or “I shall be what I shall be” “I shall be what I am” or “I will become what I will choose to become” or “I will become whatsoever I please” or perhaps (if the verb is causative) “Who causes to be” “Who gives life” or “Who causes to exist.” There are, I take it, only two possible reasons why God would tell Moses a name like that. It would have to have been in order to obfuscate and confuse, or to imply unfathomable holiness. You can guess which rationale I think is obvious. The outcome, however, was far from settled. Even though the god of the ancestors preferred to not to be on a first name basis, in a world of gods with famous names, Moses and a majority of his spiritual descendants didn’t think a nameless god would work out well. Beginning soon after the burning bush encounter in Exodus 2, Israelites coined and borrowed a large number of names which they used and often even enunciated when they came across YHWH in writing. Pious Jews, still later, hesitated to use any name for God. It became very confusing after all. At least the gender of God was clear from the beginning. Wasn’t it? Rabbi Mark Sameth submitted an opinion editorial to the New York Times in which he sought to correct our certainty about God as Father, He and Him. Rabbi Sameth says that YHWH was ambiguous not only with regard to tense (present or future) but also with regard to gender. In fact, the Hebrew Bible, when read in the original language offers a highly elastic view of gender. And I do mean highlyelastic: in Genesis 3:12, Eve is referred to as “he.” In Genesis 9:21, after the flood Noah repairs to “her” tent. Genesis 24:16 refers to Rebecca as a “young man.” And Genesis 1:27 refers to Adam as “them.” …In Esther 2:7, Mordecai is pictured as nursing his niece Esther. In a similar way, in Isaiah 49:23, the future kings of Israel are prophesied to be “nursing kings.” …In the ancient world, well-expressed gender fluidity was a mark of a civilized person. Such a person was considered more godlike. The idea of “nursing kings,” Sameth says, was derived from Hatshepsut who succeeded her husband Thutmose II and became one of Egypt’s greatest Pharaohs. That sets the stage for Sameth’s assertion that “the four-Hebrew-letter name of God … YHWH … would have [been] read … in reverse as Hu/Hi – in other words the hidden issue of God was Hebrew for “He/She.” In that ancient context, this would merely have been another way to indicate that God was too holy and remote to be too specific about. Sameth’s conclusion is, “…The God of Israel … was understood by its earliest worshipers to be a dual-gendered deity.” Now, having the benefit of 3000 years of cogitating on this, we have added several solid layers of certainty about God’s identity that earlier people would not have dared or dreamed of doing. Conveniently, it all fits neatly into our binary he-she social construct and rejects he/she as a possibility. Our refusal to look critically at our socially-biased belief probably wouldn’t matter if it weren’t being used as ammunition to slaughter each other in the name of the nameless god with many names. Fortunately, I learned from Rabbi Sameth, we do not need to object to the growing consensus about gender fluidity on Biblical grounds. HE/SHE was rather huffy about mortals being too inquisitive and adamant. Footnotes: Rabbi Mark Sameth’s article appeared August 12, 2016 in the New York Times. Downloaded: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/13/opinion/is-god-transgender.htmlwww.nytimes.com/2016/08/13/opinion/is-god-transgender.html A full discussion of YHWH can be found online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tetragrammaton

3 Comments

Aline Russell

8/15/2016 10:22:03 pm

Fascinating! I had no idea about YHWH or about the many examples of "highlyelastic" references to gender!

Reply

8/19/2016 04:11:16 pm

Aline, I think that in the case of kings, they nursed the kingdom. It was a metaphor, although Rabbi Sameth should probably speak for himself.

Reply

Lois

5/20/2017 10:38:16 am

Explain the meaning of Psalms 83:18

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed