|

A village funeral is one of the most common and complex events in village life. Briefly, it is a final tribute to a member of the community, an expression of sympathy for the family and friends of the deceased, a religious reminder of the realities of life and death, a community bonding activity, a way to make merit to balance one’s karma, re-alignment of relationships in the family and community, and (not least important by any means) guidance for the spirit of the deceased to leave the village.

Funerals comprehend the whole range of emotions and concerns: that death is suffering which is only partly softened by knowledge that it is universal, that the community has been weakened and reduced which is only to some extent repaired by the experience of the whole community being involved in funeral, by fear and anxiousness about ghosts of the deceased and others which need to be addressed as effectively as possible, and by concern to aid the deceased as much as possible by performing meritorious acts in his or her behalf. Since the most meritorious acts possible are those that support and promote the spread of Dharma, which is done by monks above all, monks have a central role in funerals even though the Lord Buddha left no instructions regarding ceremonies to mark life passages. Resources and participation of every available, able member of the village is expected at funerals. Here in Northern Thailand nearly every aspect of the death, funeral and cremation of a body is public. It is as far from the remote, misty, pastel process in the USA as imaginable. In the first place, many people die at home, especially if their deaths are anticipated and considered inevitable. Family is close at hand. If death is imminent, attempts are made to have the dying person fix attention on the Lord Buddha and possibly to enunciate one of the names of the Buddha. When the death occurs the family makes the immediate decisions about the funeral, what auspicious day it will be concluded, how many nights of ceremony and chanting will precede it (normally 3), and who will be arranging what. These decisions are matters of discussion which gradually become firm. One consideration is cost. Funerals can be elaborate and expensive, but there is nothing to be gained from ostentation beyond the family’s means. Nor, for that matter, is embarrassing frugality appropriate. A person’s status in village society is already clear to everybody. But the village as a whole, and not just the family, contributes. There are 2 contributions of money. One is made to a funeral fund, which is a voluntary insurance association. Every member of the association contributes a small fixed amount whenever anyone dies. The association pays out a lump sum to help the family defray expenses. But there is a second collection during the evenings and the last day of the funeral made by family, neighbors and acquaintances from far and near that is called “merit making”. The money is given to the family and may be their resource to pay hospital costs or accumulated debts of the deceased. In our village it would be unusual for a family not to “break even” or even have a small surplus after the funeral and cremation. Some things cost money that comes from the family. The first expense is for a casket. Since cremation is common most caskets are made of combustible wood. Size and decoration varies, but in our village the casket is usually enclosed in an outer casket that is more elaborate. It was a contribution by a member of the community and simplifies matters when people are deciding on what casket to buy and burn. The body of the deceased is ceremonially bathed. That includes, in some cases, just pouring water over one hand of the body, which is then placed in the coffin. In our villages the entire body is given a soaking. In earlier times bodies were preserved from the time of death until the cremation by being stored with blocks of ice in the casket. If bodies were to be kept for a longer time, as in the case of paupers who were cremated as a group from time to time, or as is still the case with important monks or royalty, the bodies would be placed in specially designed containers and the body fluids would drain away until the bodies were desiccated. Now, as far as I know, it is universal to have the body “protected” by formalin injected intravenously, replacing the blood. But no attempt at cosmetic preservation is attempted. The family also invests in a catafalque or platform (prasat sop) to hold the casket on the day before the cremation and during the cremation, if it is out in the open (about which more later). This framework is highly symbolic. It can be relatively simple or quite elaborate. But in any case it represents all the things that a Buddhist temple building symbolizes. It is many-tiered like temple roof-lines, depicting the “world mountain” or the world axis. In other words, it is a symbolic link between heaven and earth, between the next destination for the spirit and the present residence. But the decorations are two-fold, standing for time-honored cultural traditions while also suggesting nobility and human dignity, giving final honor to the deceased. There are craftsmen who produce these catafalques and the necessary accessories such as the three-tailed banner (see: www.kendobson.asia/blog/three-tailed-banners). They are pre-fabricated and assembled on site. Another expense is for flowers. (See: www.kendobson.asia/blog/flowers). They are provided by florists these days, although not long ago they would be collected and arranged from whatever was available in the community. Since the funerals here in our village are all conducted in homes, and since crowds of friends, neighbors and family will need to be accommodated, men of the village are recruited as soon as the death is announced over the community public address system to help set up “tents” which are open sided awnings made of metal pipes with plastic-cloth coverings. These arrangements are completed with fluorescent lights and oscillating fans. The village owns these “tents” and they are available for whoever needs them. Plastic chairs also come from the village stock, as well as tables, cooking equipment, dishes, glasses and everything needed for feeding large crowds. In fact, families generally make donations of some of these supplies for the community or the temple as part of their merit-making in memory of dead relatives. Each evening after a death until the day of the cremation there may be a ceremony which family and neighbors attend. If the deceased is well known these evenings may attract large crowds and the affair will include a meal for those who have traveled to attend. There may also be exhibitions of pictures or a video production that reviews the life and accomplishments of the deceased. A memorial book is usually produced for guests to take away. The book is usually a collection of chants and mantras for meditation, and may include an obituary of the deceased. But in our village such extravagances are rare. But even for the most modest ceremony there will need to be some refreshments and ice water. This is not just for purposes of hospitality and to assuage grief. Since these ceremonies are for the benefit of the deceased the entire undertaking must be effused with emotions of gratitude. Meritorious actions are beneficial only insofar as they are received with gratitude. As the monk’s sermon is apt to mention, we cannot be certain of the disposition of the spirit of the deceased, but we can create as much gratitude and thankfulness as possible. The largest expense is for the final religious service, the community meal, and the actual cremation. Crews from the village do the food preparation and cooking. The family decides on the menus, which can vary from quite modest to very expensive. However, since the food is cooked locally, in most cases, the cost is just for the purchases from the market. If the family is better off financially, it has become common to hire the big final meal catered. For the final service a chapter of monks will be recruited. Since funerals are inauspicious occasions, the monks will be an even number; eight is normal. When they have all arrived the “ajan wat” (a lay leader who knows the laity’s chants) will begin the ceremony, the chapter of monks will chant traditional stanzas from Buddhist scriptures, one of the monks will chant a sermon (which may include some impromptu additions, or be entirely ad-lib) and the ceremony will conclude with water pouring as chanting is going on. During this final portion of the service the deceased will be featured in the chants and the family will be mentioned prominently in ways that are very similar to Christian prayer. When the service is over there will be a ceremonial meal for the monks, and everyone else will eat at the same time. Funerals are one of the times when almost everybody in the village eats together. As many as 100 men and women (fully a quarter of the village) will be involved in meal preparation, dismantling the “tents” and sending the borrowed equipment back to the village hall for storage. After the meal the trip to the cremation grounds will be lined up and then a procession will either ride or walk en mass. When people arrive at the cremation grounds they are generally presented with a souvenir as an expression of appreciation from the family; it may be something quite simple, such as a tiny jar of Tiger Balm ointment. At the cremation grounds the monks will again chant. Then they will ceremoniously remove packets of monk’s “robes” from atop the casket, which is a tradition hearkening back to the pre-Buddhist past where religious ascetics got their garments from cloths left at cremation grounds. It is said that the reason Buddhist monks’ garments are yellow is because saffron was the cheapest dye in North India, very much the same rationale as Franciscan monks in Italy used dark dye for their robes also gathered from cemeteries. When the monks have finished, the “undertaker” will prepare the body and coffin for cremation. Legs of the coffin will be knocked off so it does not tip over. The lid of the coffin will be opened and the undertaker will anoint the corpse with pure coconut water. Cracking open the coconut could be what is left of a more ancient act of cracking open the cranium to release the spirit. If the body is a woman it will be turned over, face down. This is often accompanied by loud calls for the spirit to depart. The actual fire can be lighted in several ways. One of the more spectacular is to have one of the monks light a rocket attached to a wire that leads to the pyre. The fire also sets off fireworks that include aerial bombs (if the family can afford it) to signify the finality of the cremation and also to further dissuade the deceased’s spirit from trying to linger. More and more cremations are done in modern crematoria, which are ovens fired by electricity or gas. In this case there may also be fireworks but it is the smoke from the crematorium chimney that is to be noticed. The prasat sop is burned at the same time. With that the ceremonies are over. On the second morning after the cremation the closest family members with 2 monks will collect the cremated “bones” in a white cloth prepared just for this. The bones are pulverized into dust and then after the priests chant briefly the powder mixed with phosphorus is ignited and expelled into the heavens. That’s how village funerals are done around here in our villages in the North.

0 Comments

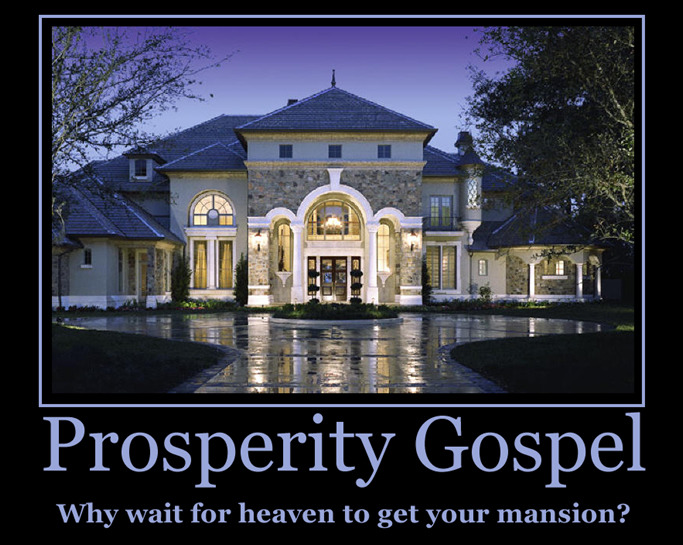

“Prosperity cults” and “prosperity benefits” are two phenomena that need to be distinguished and understood. Both are wrong from many perspectives. But they infect modern religions just as they did Medieval and Ancient ones.

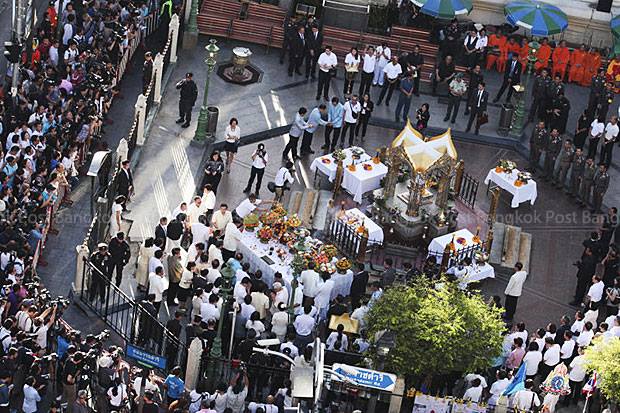

To begin with the extremes, John Oliver, a TV personality in the USA whose weekly show lambasts and sometimes lampoons popular movements and beliefs, recently highlighted Christian televangelists who fill the airwaves with promises of divine rewards to the faithful who send in money, which the TV preachers use to buy jet planes and mansions. Earlier in the year Al Jazeera jolted Thailand with an investigative documentary about similar shenanigans going on with certain monks and cults. A bit earlier, a Hindu cult in India so large it yields political clout was subjected to the same futile exposé. I say futile because exposure of the truth seems to have little impact on the way people hand over money to these operators. What are the characteristics that show these are “cults” as I have called them? I propose 4: 1. There is a single person in authority with no apparent outside accountability and no transparency about how decisions are made or reviewed. The preacher or guru is not functioning in response to higher authority. 2. There is a direct link between donations and access to the “center” where blessings are most abundant. In one famous Thai cult seating in the vast circular hall is allocated according to the size of contributions. In other cults access to esoteric knowledge is reserved for the more faithful. If faithfulness is determined by monetary measures you may confidently assume the organization is a cult. 3. The main attractiveness of the cult is its reflection of a consumer/elite/power mentality. It is good because it is grand. It is grand because its promises are extravagant. Anyone can prosper beyond their present circumstances according to prosperity cults, but those with the most to invest will, “naturally”, prosper most. 4. It is a cult rather than a scam if the leader actually believes that prosperity accrues to those who invest, “plant seeds”, or contribute. It is, of course, impossible to know what is going on in the leader’s mind unless there happens to be some unguarded moment when the leader ridiculed the gullibility of contributors, or a major lapse of the expectations of the faithful (as when the leader is caught living a lie). If the leader believes there is really no link between a person’s donations and the person’s prosperity a scam is being operated. Far more pervasive and detrimental to all religions I know of, is the expectation of benefits from religion. In fact, I can anticipate protests from some of my own religious friends and family when I say that valid religion makes no promise of benefits. None of the world religions do. Yet most people believe that the very purpose of religion is some sort of benefit. Here are just a few: · Prayer brings results · Religion builds better citizens · Religion promotes peace of mind · Religion connects one to a Higher Power · Religious practice assures one of a better life after death · Meditation results in a higher level of consciousness · Religion promotes social order If religion does not provide assurance of any of these benefits, what’s the use? Not a few of the lurches forward for institutional religions were propelled by just such promises of rewards. The “Great Awakening” of the 18th century in Christianity was built on the promise of deliverance from hell-fire and damnation. The Neo-Pentecostal movement and its daughter the charismatic movement promised healing, divine guidance, and solutions to issues of daily life large and small. Buddhists where I live expect their meritorious actions to bring results. Sometimes specific prescriptions are made for one to undertake particular exercises or rituals to bring some form of needed physical, economic or social prosperity. Still, in Buddhism as well as Christianity and Islam, people are sanguine about the possibility that the benefits might be delayed beyond this life. It is enough if life is rendered at least tolerable. So, if these benefits are not why religion is practiced, what is religion all about? And why would we want to undergo its rigors? In classical Buddhism the Lord Buddha discovered the way to extinguish one’s ego, and thereby end the repetitive cycle of birth, aging, dysfunction and death. Meanwhile, for those unprepared or still unqualified to achieve the breakthrough to enlightenment, a robust society can certainly help combat and mitigate the effects of sickness, war, famine and despotism. There are two basic narratives in classical Buddhism. One is of the Lord Buddha’s encouragement for individuals to achieve enlightenment, and the other is his instructions for forming religious communities in the midst of secular communities for mutual support. There is nothing in either of these narratives to encourage the notion that following the Lord Buddha’s teaching and example leads to prosperity. In fact, the theme is to forgo the lure of prosperity. In classical Christianity, Jesus had a lot to say about prosperity, all of it critical. Longing for prosperity (e.g. “love of money”) is an impediment to one’s ability to follow Jesus. For a millennium martyrdom and asceticism were standards for Christian perfection. Protestantism softened these indicators while sharpening the insistence that Christ has already accomplished everything that is ultimately important. There is no further need to strive for salvation. But this life is perilous and there is evil loose which is beyond our power to oppose without help as we travel “life’s way” along an indistinct path. We need nurses, guides and all manner of fellow travelers who are willing to sacrifice some of their personal well-being to help stragglers and strugglers. Indeed, we take turns, sometimes being those who are in need and at other times being the ones who can provide assistance and consolation. Those who abandon their companions and divert their journey in order to concentrate on acquiring benefits or other forms of enhanced prosperity fail to understand both their integral involvement in humanity as a whole (for the vast majority of whom circumstances are dire) and also the urgent injunctions of Christ. And that is where the prosperity gospel and prosperity cults are not simply benign mistakes but pernicious diversions. What the prosperity gospel loses is concern for others. The most generous thing that can be said is that for some engaged in the pursuit of prosperity their concern is also for their kinfolks and those with whom they feel kinship. The rest are severed into “others” and either left to fend for themselves or helped conditionally. A world so splintered is a world endangered. Life in such a world cannot be sustained indefinitely. Prospects are made bleaker for the majority of humanity when prosperity religion prospers. An explosion at a major shrine in the heart of Bangkok at rush hour on Monday night, August 17 which killed 20 people and injured about 130 others, raises the question again, “How fragile is Thailand?” [Thanks to the Bangkok Post for this picture on Facebook of 5 religious groups on Friday, August 21 honoring Monday’s victims; see http://www.bangkokpost.com/news/general/664608/ for the story. Thanks to Kamolrat Surakit for the picture of the Christian participants, in which all branches of the Church were present. How vulnerable can a country be when all major religions coexist peacefully?] Still, there are a surprising range of answers to the question of Thailand’s viability, which seem to depend on the pundits’ interest in particular issues. In general no one expects the country to collapse but the vulnerable points are worth listing.

1. ECONOMY Thailand’s economy has cooled down. Thailand is no longer listed as one of the Asian Tigers. Some wonder if the coming of the ASEAN Economic Accords on December 31 of this year will expose the economy to ruin, as key protective taxes and laws will presumably expire. Others worry that Thailand’s whole banking system is linked to artificially inflated real estate values leading to massive unrealistic debt. 2. EXPECTATIONS Thailand has developed a growing middle class with elevated expectations. Those expectations are basically two: that education will entitle one to income that does not involve concerted manual labor, and everyone is entitled to an education. Further, income should be sufficient to not only free one from hard work but also to provide a higher level of necessities, goods and services that used to be considered luxuries. To make up for a reduced work force in labor intensive parts of Thai life (agriculture in particular, but also construction and industry), mechanization and immigrant labor will be relied on. Meanwhile, jobs with higher skill levels will have to expand. This is a pyramid scheme, some insist, meaning it is not sustainable. 3. FOREIGN RELATIONS It is sometimes overlooked that this is one of the rare times in Thailand’s history that there is no external threat to its sovereignty and territory. Indeed, now that there is no realistic outside threat the vast military is redundant unless there is an internal threat, which is constantly being identified. Some say it is being manufactured through incompetence and others say it is by design. Pretty much everybody feels that at some level the greatest threat to Thailand’s stability and prosperity is the military itself. 4. CULTURE Cultural monitors are constantly concerned about the erosion of Thai culture by globalization. The developing and expanding areas of language, arts and to some extent religion are innovative, or imitative of other popular cultures. It is hard to maintain anything uniquely Thai in any area that is widely popular. Classical arts are not popular. Pop culture is not traditional. The worry is that if unique Thai culture fades, so will Thai identity, and then all will collapse. It’s a long-term process, but constantly mentioned. 5. SUCCESSION Finally, comes the question of loyalty of the Thai people to the institution of the Royal Family, and to whatever sovereign should follow His Majesty the King now revered but with health issues. Seen from outside the country, the entire social elite in this very hierarchical and patron-client society is vulnerable if the Royal Succession is vulnerable. Ironically, the very apparatus that is designed to deflect public interference or participation in royal affairs is the thing that makes the institution appear to be vulnerable. It is highly questionable that if this, one of the last of the Royal households in the world, were to be replaced by a republic that Thailand would crumble. No doubt the elite would have to scramble, but the country is not that fragile. Stressed minorities always have trouble finding allies to help them advocate for relief. The gay and lesbian movement is no different. But it is important to be clear about what relief is being sought.

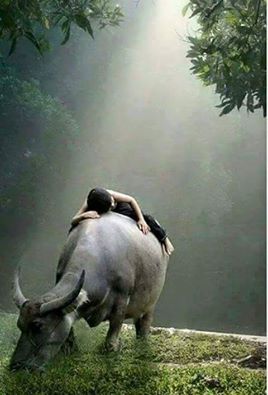

If the goal for LGBT constituencies is civil rights, our allies might be others looking for civil rights. Here in Thailand those might include the feminist movement, religious-cultural minorities, stateless migrants and refugees, or landless villagers. If the goal is status and respect, potential colleagues might be those stigmatized by handicap or disfiguration, by diseases such as leprosy (Hansen’s Disease) or HIV-AIDS, by sex work, or by their criminal past. Here’s where the trouble is. An alliance needs to be large to be noticeable and powerful, but the more diverse the alliance the more targets there are for the opposition. For this reason alliances are hard to form and fragile. Thai feminist professionals looking for ways through the glass ceiling see only peril from having their efforts compared to those of transgender women and lesbians, much less to professional sex workers. What have ethnic Karen villagers wanting Thai ID cards got in common with same-sex couples wanting marriage certificates? Gay entrepreneurs in high-rise condominiums on Sukhumvit’s golden miles want respect money can’t buy but certainly don’t imagine affinity with kathoey boys on the streets below or with former sex criminals is a way to get respect. So formidable are the obstacles to alliances, that few advocates would see any advantage in trying to form them. It would be better, wouldn’t it, just to forge an identity, as commercial brands build recognition? Notoriety builds fame fastest, but that usually is not how to garner respect, even though it works well for book sales. For the most part, public recognition for a social movement takes time, luck and patience. A lot of money for advertising also helps. Meanwhile, rather than narrowing focus onto particular objectives (such as removing the requirement to specify “Mr., Miss or Mrs.” when applying for a passport), it might be expedient to broaden the focus to address more fundamental objectives. That was the conclusion of a think-tank I attended this week. (See the pictures above.) Our conclusion was that for LGTK (lesbian, gay, transgender and kathoey) people, stigma comes because of failure in sex and gender education. Bias and misunderstanding are perpetuated throughout the culture because they are never challenged. That’s the place to begin. We can acquire educational resources and validation from the medical and health sectors, and begin to supply supplementary material to key people at the local level. If that is our project, and we are not mounting a direct challenge to those in power, we already have people and groups working on this. Rather than persuading them to join our movement, we can join theirs. We’re going in the same direction on the same road. It’s going to take a generation to reduce social stigma that comes from persistent homophobia and ignorance. So why not concentrate on the young people who are ready to receive knowledge-based information and who are going to be the policy makers by the time anything else we could undertake will be showing results? Water buffaloes are special. They defy categorization. They are farm animals but sometimes more than that, almost members of the family. They are given pet names. Love between a little boy and a kwai is sometimes hard to explain, but to call someone a “kwai” is a strong curse implying the person is an “idiot”. As if to counter this aspersion, a buffalo culture center has been built in Supanburi (an hour north of Bangkok) to show off the beasts’ ability to climb ladders and play ball. [All right, it is a reflection on human stupidity that the more like us animals can act, the more intelligent they are supposed to be; it’s the idiocy of most animal acts around the world].

On a real farm around here where we live in North Thailand, kwai were valued for their strength. They could pull plows and wagons. They were tough but (in line with their other ironies) they were also vulnerable to sun and insects. One of my former students told of sleeping under the house with the buffalo to keep a smoky fire burning at night to repel mosquitoes. Many farm children spent days of their lives tending buffaloes while they grazed and wallowed in the mud during the heat of the day. Buffaloes still pull plows in outlying districts, but in our valley they are gone. The most beloved got old and died. The less lucky ones were sold in the famous Sanpatong cattle market or were taken directly to slaughter houses to be turned into meat sold at special prices in fresh produce markets. Kwai meat is favored by local connoisseurs of raw minced meat and blood dishes such as ลาบ หลู้ ส้า because the flavor is thought to be better. The era of muscle power and self-sufficiency is over when the kwai are gone. Part of the culture almost as deeply engrained as elephants is gone. No more folk singing groups will choose the caribou as a symbol of their advocacy of the dignity of subsistence farmers. A coming generation will not be able to relate to the school-book stories of their fathers, nor to romantic pictures such as the one at the top of this essay. RICE PLANTING is in full swing in our valley. The rainy season is officially here on this weekend after Asanha Bucha Day. It is the beginning of Buddhist lent. The tradition says that the Lord Buddha instructed his disciples to stay in their monasteries during the rainy season in order to keep from traipsing across rice fields damaging the newly planted crop. This, we are told, was a very compassionate precaution.

Rice is the main food of Thailand as well as the main export product. In the late 19th century HM King Chulalongkorn, Rama V, mandated the expansion of Central Siam’s irrigation canal system. This opened up large tracks of land for rice farming. The produce far exceeded domestic need so an agri-industry developed to buy farmers’ excess rice and ship it abroad. Soon rice export values surpassed teak, up to then the main source of foreign exchange. With the development of reservoirs, a second rice crop became possible. Faster transportation expanded agricultural export possibilities to include fresh fruit and flowers. Advanced processing capacity has opened still more options to include soy oil, corn oil and corn meal, palm oil, coconut oil and canned, dried, pickled and candied fruit, especially oranges, pineapples and lameyes. Farming has grown from a seasonal occupation to a full-time, year-round possibility. Slowly, farmers have eased into the lower middle class, but in vast numbers. Even though the “middle-men” still work less, take fewer risks and make more profit, laborers have increasing expendable income and clout. The sheer bulk of the agriculture-based, laboring, lower-middle class has nearly leveled the balance of power between clients and patrons. The elite and those in the upper middle class still have control but they are hanging onto it more nervously. Rice production methods are an excellent example of how the change has come. I am watching the evolution from my windows overlooking rice fields and orchards. This year, large (well, middle-size) tractors with roto-till plows were used on our rice fields for the final plowing. Just a year ago transitional technology was used. (see: www.kendobson.asia/blog/how-now-to-plow) A few years ago water buffalo pulled the plows. That by-gone age was non-mechanical, muscle-powered, intimate, hands-on farming. The transitional era replaced muscle-power with motor driven plows, still guided by hand by farmers walking behind. Farmers called their machines “metal buffaloes”. This was still hands-on farming with the farmer in intimate contact with the soil, knee deep in mud. But in the emerging, current era the tractor driver sits above the mud piloting a machine, pulling levers while the farmer stands on the side of the field and watches, waiting to pay for having the field plowed. The only foreseeable technological advance would be robotic tractors directed by humans from a distance or entirely by computer. This is not, I think, the direction development will take. If agribusiness elsewhere is any indication, growth will be in terms of size of fields and equipment rather than computerization. But rice planting still generally includes an age-old aspect. The transplanting of rice seedlings is still done by hand, knee deep in mud. Broadcasting seeds onto a field reduced to slurry is not yet popular here in the North. As long as rice needs to be transplanted from seed beds into plowed fields it will be hands-on. When the fields become large enough to eliminate the transplant-phase the farmers will no longer own their land and will begin to grow distant from the production of their own food supply, and ours. The emphasis will shift away from a balance of tradition and common sense to maximized production without regard for impact on consumers or the environment. At the same time the annual agricultural cycle will fade in importance to villagers as it has for metropolitan dwellers, and culture and religion will change. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed