|

Professor Virgil Verbal’s classroom in Hogwarts castle was a semi-circular shape which was useful in many ways. In the first place, from time to time the students sat in two or three rows facing the center where something was going on. Professor Verbal rarely lectured, but often read aloud and sometimes acted or performed. More frequently groups of students did that. Some of the time the students were involved in composing ideas, which was the way the professor referred to writing. “It is much more than writing, don’t you see,” he would say. “The writing is the part that happens when the ideas are trying to escape. You capture them with your sharp pens while they’re still squirming around in your head. They can’t get away as easily when they’re all spread out in view.”

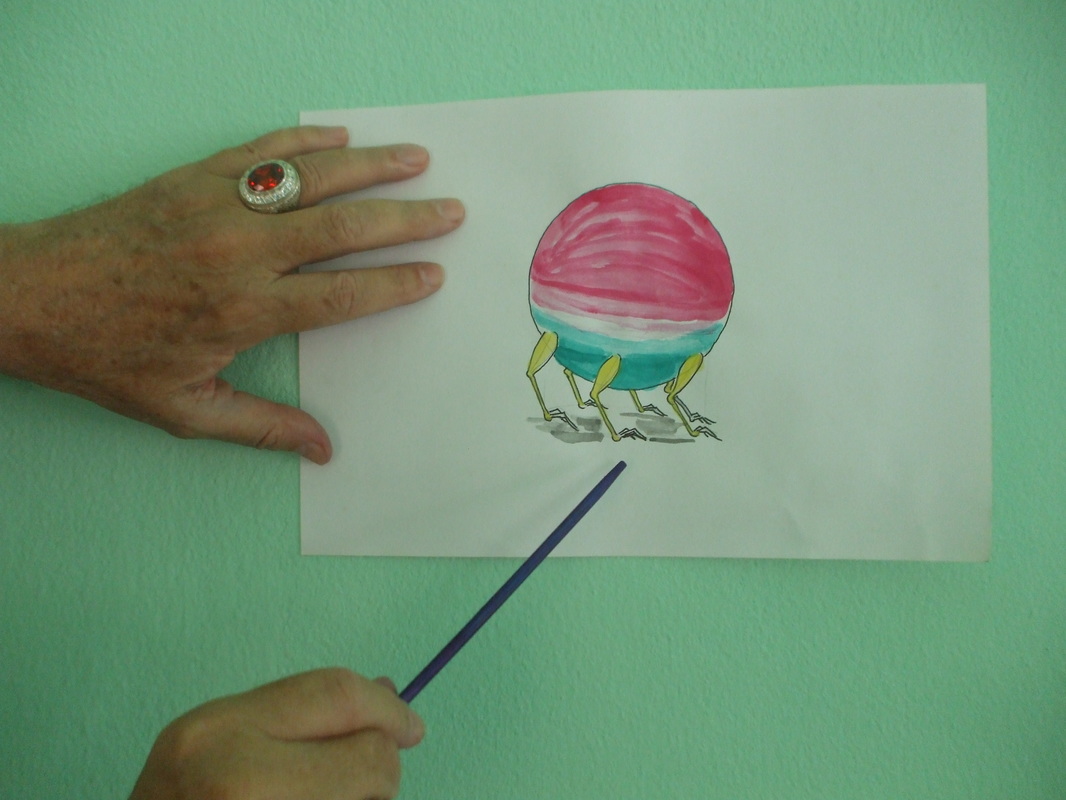

“Oh yes,” Professor Verbal said enthusiastically one day, “language is quite as magical as any hex or charm.” The students laughed at this absurd idea. “Come, come, don’t make it so hard for yourselves,” Professor Verbal came back at them. “You can all learn how to make words turn into images or ideas. Some of you are quite good at using language to draw attention toward something you want people to notice.” The students chortled again. “Oh, indeed! Just a few well chosen words can send minds racing far away, or re-create a time and place that once existed or conjure one up that never existed at all. With words you can make people think or forget. You can have the power of the dream spinner.” “But dreams aren’t real,” a student objected. “Whatever gave you that idea?” Professor Verbal responded. “Well, when you wake up the thing you dreamed is gone,” another student picked up the challenge. “So it’s all in your head.” “Oh, you mean that a thing is not real if it does not exist somewhere else as well as in your mind. I think a thing might be quite real even if it were only a dream-like thing. Let’s try an experiment,” Professor Verbal said, as if he were making a suggestion rather than uttering an imperative. “With words alone, I will describe something and we will see what we can see with just what’s in your head, without anything ever going first through your eyes.” Professor Verbal got a far-away look in his eyes and began, “I-bows are about the size of watermelons but quite round like basketballs. They are pink on the top and green underneath, green as a mint leaf. Each of the I-bows has six legs, like the legs of a bird, with three toes on each foot. The legs are evenly spaced all around and the three toes on the feet face in the direction the I-bows want to go. There are no other things visible, no eyes or tails, for instance.” Professor Verbal then took a deep breath and finished, “Now, draw a picture of an I-bow.” When the pictures of the thirty students were finished Professor Verbal posted them all around the outer wall. As the students walked around admiring the work and comparing each other’s pictures to their own, Professor Verbal spoke to them. “That is the magic of language. Nobody has ever seen an I-bow but you could all draw a picture of one. What’s more, almost all your I-bows are so much alike that if a person knows what one I-bow looks like they’ll know that something else that looks like that is an I-bow. Shall we give it a try?” Matching his actions to his words he went to the door and called in two students who happened to be in the hall. The teacher held one of the pictures in his hand. “This is an I-bow,” he said and then repeated it, “an I-bow.” Then he gestured toward the pictures on the wall. “What are those?” The two students looked back and forth between Professor Verbal and the pictures as if they were hoping for some clarifying reason for this quiz or perhaps an inspiration, but after a little while both students surrendered. “They are I-bows?” they said with their voices going up as if they were trying to straddle the line between an indicative and an interrogative statement. “Yes,” Professor Verbal nodded sagely, “if one of them is an I-bow, it would be reasonable to conclude that all these splendid portraits are of I-bows. Would you be surprised to learn that no one has ever seen an I-bow before this very hour?” Professor Verbal asked the two visitors who were smiling faintly and edging toward the door without answering. “Well, thank you for confirming our discovery.” When the two visitors had gone Professor Verbal turned again to the class. “So you see, it is not necessary for a thing to exist anywhere outside our mind for it to be real enough for all of us to have a fairly large consensus about it – as long as there is language to make the necessary connections. That’s the magic of language. “Now, would you say that an I-bow is more real than a penguin?” he asked, smiling good naturedly. “Less real,” several students assured him. “Well, let’s put it to a test. How many of you have ever drawn a picture of a penguin?” A few hands went up. “Not as many as have drawn a picture of an I-bow,” he observed without bothering to count the hands. “But maybe your having drawn a picture of something is not the only test or even a valid test of something’s existence. How many of you have drawn a picture of my grandmother?” the professor asked. No hands were raised, but a titter went around the room. “So we can agree that some things, perhaps most things in the world, are or were very real even though you cannot draw a picture or even take a photograph of them. Is the problem because of your artistic or technical skill?” “We don’t know what your grandmother looked like,” a student protested. “Well, let’s say that’s because I haven’t described her to you. We haven’t had the words.” “We could do better from a picture than your telling us,” one student challenged him. “Well, I happen to have a picture of her,” Professor Verbal conceded. A few seconds later it was being projected onto the front wall which served as a screen. “Confucius is said to have said that a picture is worth ten-thousand words. Let’s try that out.” Verbal drew a card from his pocket and held it up beside the picture of his grandmother. They were the same size. “The card has about a fiftieth of ten-thousand words. Listen. “Lottie was born in a shepherd’s cabin in the highlands of Scotland where the birds taught her to sing, she said, and the sheep and her father taught her everything else that was important. The most crucial day in her life was in the winter when she was ten. There was a highlands blizzard and her father was lost in it. There was no food in the hut and the fire burned out. It would have been death to go away from the hut, but it was deathly cold inside. Toward evening Lottie heard some bleating. A few sheep had wandered up to the sheltered side of the cabin. Among the sounds outside she recognized the high-pitched stutter of a little lamb. ‘It’ll freeze,’ she told herself and she decided to rescue it. The lamb was easy enough to find, but its mother was not about to let the girl take it away from her. ‘Well, inta th’ cabin wi’ye,’ Lottie said. Before she could get the door shut there were seven sheep in there. After a while, their bodies warmed the room a wee bit and so they survived the last full day of the storm until Lottie’s uncles could get to her.” “Which tells more about my grandmother, the photograph or the two-hundred-word story?” Professor Verbal asked. Some students were sure the right answer was the story. “But why is the story a better look into my grandmother’s life than the photograph?” “It tells more, the story does.” “Does it tell us what she looked like?” “No.” “Well what does the story tell us?” “How she stayed alive and kept the lamb alive.” “What else?” “That she cared about animals. That they would come to her. That she didn’t panic and run.” “So is that what you’ll remember from the story, that Lottie was courageous, compassionate and lucky?” “Yes,” some agreed. “I doubt it,” Professor Verbal shook his head. “No,” Anthony admitted, “I’ll remember the little girl in the hut with the sheep keeping warm in the blizzard.” “Ah, the thing you’ll remember is a scene you can picture, a key part of the story. The picture in your mind is what will help you recall the abstract parts of the story, but the story is more vivid and informative than the photograph we saw. “One last thing about the power of language: why does it have power? Think about what you do when you listen to a story you are very interested in. Your ears take in the sounds and your mind makes connections with things you have stored in there. Lottie, sheep, cabin, blizzard. Notions of what these may be like are pulled into your conscious mind which is very busy as you quietly listen. You are in a very active frame of mind when you have to conjure up the pictures to fill in the blanks. It is easier to listen to a description when there are things to compare it to. I-bows are round like basket balls, the size of watermelons, with three-toed feet on legs like birds. You can picture an I-bow by assembling those parts in your mind. Your mind is very busy. “But what happens when you see a movie? What does your mind have to do? If the movie is like most of them your mind doesn’t have time to do anything but receive the images. The picture is full and your mind has to absorb what is given to it. The less it flits around the better, because you can absorb more. You must be passive. “Language is the most magical art form, students, very magical.” Professor Verbal straightened up and waved his wand so that the pictures of the I-bows flew off the wall back to their artists.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed