|

“The first thing that happens once you have been accused of breaking a social code … The phone stops ringing. People stop talking to you. You become toxic.” “Here is the second thing that happens, closely related to the first: Even if you have not been suspended, punished, or found guilty of anything, you cannot function in your profession.”

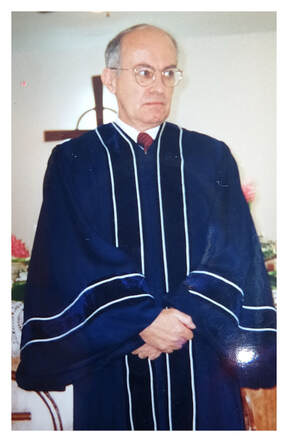

How true. Back 20 years ago this is how my pastoral career ended. I was accused of breaking the social code that required me to demonstrate my cis-orientation. I was given the choice of dismissing Pramote (my same-sex spouse) and living un-controversially, or finding my way outside the church. I decided to see who would continue to contact me. The phone stopped ringing. Then I was warned not to try to re-activate my pastoral credentials but to just stay off the rolls of any pastoral or missionary list. That was clarified, “Stop doing anything as a clergyman.” I was to hang up my robe and find another job. I reckoned it did not matter in terms of my ability to function as I had been, conducting spiritual life retreats, writing Bible studies, and teaching in seminaries. However, my ability to do those things was never counted when the time came to let me continue or let me lapse. I was never given a chance to appear and discuss this at all. Discussions about me were held without me. It was no longer my abilities that mattered, but my social misconduct. Upon further reflection I think it is unclear that my knowledge, skill, and “call” were ever as important to my functioning as a pastor as was my social position. I seriously underestimated that all along. I was valuable to congregations and communities because of my being the pastor. In those days (the 1960s to 80s) pastors were still valuable to congregations and communities as members of the leadership who oversaw the best interests of the people, who were leaders with various perspectives and privileged entre into private lives at critical times, and due to their collective memory. Formerly, pastors were key members of that leadership, but that was changing in the 1980s. By that time a pastor had to earn esteem. It no longer came with the title. Longevity was important, but so was a track record. Every pastor developed their own persona and standing. But it only seemed to have much to do with how good they were at their jobs as preachers or evangelists (recruiters of members), or even as chaplains to the community. Beneath it all there was a consensus about what a pastor must be that had to do with being a role-model. The right to judge these matters was firmly held by others, especially, of course, those being ministered unto. The bottom line was not “my spiritual gifts and call,” but the approval those who would call upon me to exercise the gifts. If the phone stopped ringing the pastor was done. Decisions to pick up the phone and call a pastor were never made officially by a committee or tribunal; those meetings came much later, if needed to mitigate some catastrophe. The pastor was the first to know when the phone stopped ringing. But in those days before social media it was rare for the pastor to be told why trust had disintegrated. This dynamic is not limited exclusively to pastors and religious leaders. Anyone whose position depends on acceptance by the public can find that eroded. Teachers, civic officials, celebrities, and even war heroes can sink without warning or recourse. Some are in a position to fight back and others are sufficiently buffered to outlast the incoming tsunami, but many are destroyed. Social conformity is demanded as the price for social acceptability. Nonconformists must have some immense skill or leverage. The infuriating thing about this is how little facts count for anything. When a teacher is accused of racism or favoritism, if social media get wind of it, the storm may grow unstoppably. Neither circumstances nor accuracy matter. Only a counter-storm of overwhelming support has any chance, and those who could help are often hesitant to get involved and become collateral damage or targeted as co-conspirators. Social media have made this much worse and more pervasive. Social media are invasive, relentless, unforgiving, and ruthless. They thrive on the very energies that destroy discourse and courageous inquiry. People these days feel entitled to freedom from discomfort, let alone intimidation. They presume they have the right to protect themselves by any means, even at the cost of failing to know what the world is like. This is ominous. At this rate things are going to continue toward repression, fear, and disregard for “others” as well as disdain for the very possibility that truth may exist outside one’s bubble. [Thanks to Anne Applebaum for the quote at the top of this essay from her August 31, 2021 Atlantic article “The New Puritans”.]

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed