|

REMINISCENCE

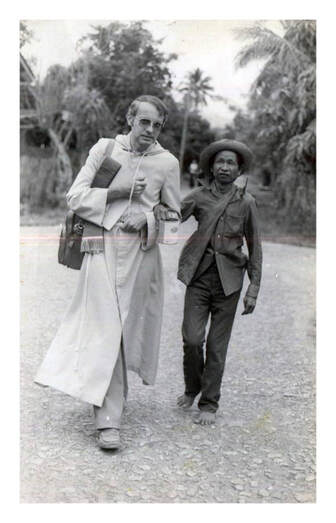

From the first year I became a teacher in the theological seminary here in Thailand in 1965 I began to realize, “We are not doing this right.” Then 40 years ago I had an opportunity to try a new approach to theological education. For a couple of years I took a group of students on week-ends to work in a cluster of village churches. The work was practical and involved teaching classes, leading worship, preaching, and sometimes interventions. Every week we’d then discuss and reflect on what had happened. What we did was reverse the educational paradigm for those “practical theology” functions (i.e. preaching, teaching, counseling, and officiating). In traditional classes the process is essentially to focus on a concept and then tell stories about how that works out in various situations. We gather in classrooms to study activities going on somewhere else. It is about principles in search of applications. On our weekends the situations came first and the concepts were identified in retrospect. It was inductive. We did what we needed to do; then we thought carefully about it, and tried to do it better the next time, if there was a next time. We were constantly surprised by peak learning moments. The best were challenges or interruptions, random and unplanned. Sometimes it was a spontaneous act that reverberated most resoundingly. [I was astonished by the ripples that resulted from my simply taking a blind man to breakfast one Sunday morning (as in the picture with this essay). Most of the student-team hadn’t realized how important random acts of kindness could be as keys to ministry.] Context was a continuous issue, without which most of the learning experiences made less sense. In fact, it was context that made every incident unique, and it was uniqueness that demanded coherent explanation, that being the threshold of theological meaning inherent in the experience. Pretty soon it happened that the learning that was taking place not only informed us about the practical undertakings in which we were involved, they were also leading to vocational and spiritual discernment that just never happened as predictably in other kinds of theological education. Another result was the evolution of community. At the outset we were a group of outsiders who came on weekends. But our group coalesced and became colleagues. The villages to which we went welcomed us as they were able, but that evolved to the point that we actually became part of the village to some extent because of how we slept on floors and ate in the market or in church halls with kids. If there was a village fair we were there, and toward the end of the year we had a fair and the whole village came. If we had not had to conform to the university’s academic requirements and calendar we would have achieved a level of involvement in which we became participants in village affairs with voices in creating the village’s future as well as expanding the capacity of the church to be effective and influential. That was a vision some of those students perceived. Even though that model was not continued by the seminary in Thailand, some of those students never lost the vision.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed