|

WHO ARE INDIGENOUS PEOPLE AND WHAT DO THEY WANT?

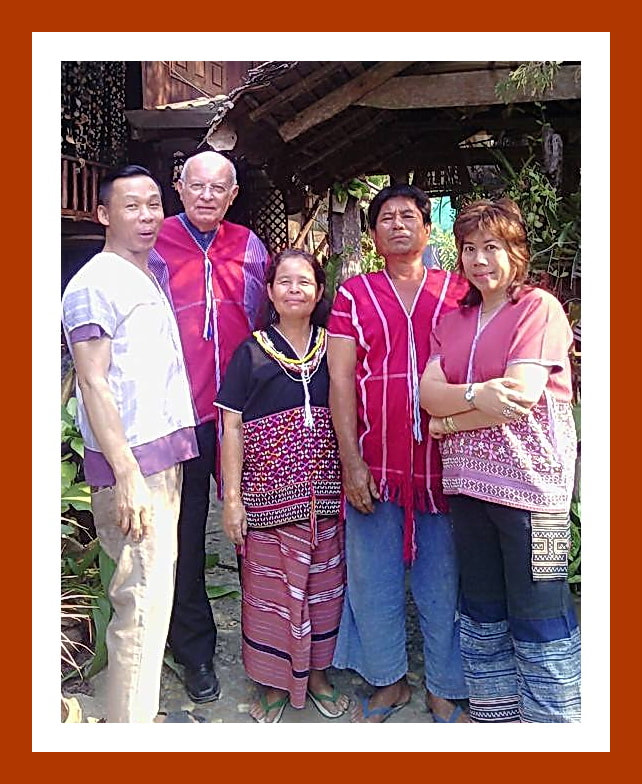

Never, since 1492, has the question been so hotly debated, “Who are indigenous people and what difference does it make?” The Persians and the Greeks accommodated indigenous people in ways that would bewilder Europeans voting for Brexit, North Europeans scared of an influx of Syrians and Turks, and white Americans building a wall because they don’t live on an island. Thanksgiving in the USA, the coming election, and the challenging season of Advent and Christmas turn spotlights on indigenous and migratory human movements and challenge the sentiment that one ethnicity must be dominant at least within a particular boundary. The harsher name for ethnicity is tribalism. It is this that has become the actual rationale for pretty much all geo-political action since … well … a long time. Just since World War Two, which could have ended international imperialism, and since the end of the Soviet Empire 30 years ago, ethnic cleansing and re-emergent tribalism have murdered millions and brought the world to the brink of insanity and (arguably) extinction. Back to the more limited topic of who are indigenous people and what they want. How can you tell? Who, for instance, is “indigenous” in the picture that accompanies this essay? This week Cliff Sloane provided an article written by Ian G. Baird, entitled “Indigenous Peoples of Thailand: A contradictory interpretation” published in Asia Dialogue, a journal of the University of Nottingham Asia Research Institute. Baird’s contradictory interpretation is that movements for indigenous rights and restitution are limited to areas where settler colonizers moved in overwhelming numbers and blotted out the indigenous culture and often most of the indigenous people. He laments that the Thai government avoids efforts to focus on indigenous sub-cultures while in other places (such as the USA and Australia) survivors and descendents have begun to try to reclaim some of what their ancestors lost. But in places where the in-migration was not across “salt water” the idea of some people being indigenous and not others has not taken hold. [Baird’s article is worth study if you are interested in Thailand’s ethnic issues, but it is also relevant to what is also going on world-wide.] I have no intention of disputing Baird. I think he is right. I just want to mention that there are additional reasons why the idea of indigenization (and race, for that matter) evades the every-day consciousness of people around here and different ways of measuring progress aside from what the government is doing on paper. (1) HM King Bumiphol, Rama IX (whose birthday December 5 is a national holiday and “Father’s Day”) and his mother made a very large impact on gaining status of many kinds for ethnic minorities in Thailand. They spent decades expanding commercial options and government services to marginalized people. Without them the country would still be ignoring ethnic diversity in favor of centralized cultural dominance and the accompanying opportunities for government entities to exploit these people. The work, however, is unfinished although the momentum toward fuller acceptance continues. (2) Cultural centralization is increased by the general preference of oncoming generations of people from ethnic backgrounds to enter the financial mainstream and gain its advantages of security and comfort. They may still wear ethnic items of clothing, but ethnic culture is selective and optional for them if they can pull it off. The drive is to get language, education, and vocations to join the mainstream. The idea of ancestral lands and customs being buried and stolen is hardly remarked on. In fact, regardless of historical reality, most ethnic minorities passively accept the idea that their lands really belong to a higher entity and they have moved uninvited onto it from where they actually belong. The motive for this forgetfulness is that they feel identified with people whose demographic center and cultural base is elsewhere. “Our people are over there.” Historical reality is that they have lived where they are for several generations and when they moved there the area was dominated by an entirely different military power than the one that claims sovereignty at present. (3) When it comes to drafting legislation and national policy, political action to accommodate ethnic sub-cultures and minority religions inevitably bogs down when it becomes apparent that whatever is done must also apply to those in the southernmost provinces. The Muslim population in the 3 provinces bordering Malaysia has never been reconciled to the military and political take-over of their Pattani Sultanate by the Bangkok government 150 years ago. The least that must be done is to acknowledge their religious rights. This sometimes works to the advantage of minorities, holding the zealous majority at bay from such things as declaring Buddhism the only national religion, but often simply results in the parliamentary political conclusion, "We're not going to touch that, yet." So the government signed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples without being able to specify what to do about those rights. (4) Baird makes an excellent argument for seeing the drive for making ethnic cultural rights official as being restricted mostly to places where settler colonialism took place, whereas elsewhere it has been common to disregard cultural minorities because "they are just varieties of us, after all, deep down." "Just more of us" breaks down, of course, when things like full citizenship or property rights are opposed for "some of us" who are really "actually them." Meanwhile, some of the old ways are being neglected, and cultural knowledge is slipping. Nostalgia is a motive to hang onto some of it, and commercial possibilities tend to help. When ethnic textiles or household utensils become marketable, it’s considered a “win” and hardly anybody objects that the products have to be repurposed to sell. At the base, where it matters most that an ethnic culture is valued and fought for is whether the language, activities of daily life, and opportunities for children growing up are thought to be better inside the ethnic culture or not. (5) If the dominant culture begins to lose its allure, especially if there is rot perceived in its elite, previously subjected sub-cultures may re-emerge. As time goes on, for example, Lanna history and mores are being reasserted and the prevailing narrative of the North being rescued by Bangkok is being disputed more openly. This ability to tell a different story about how Lanna was conquered rather than liberated, in the face of fierce opposition by the story-spinners in Bangkok, is ironically enabled in part by the momentum that continues to sustain and empower other ethnic cultures whose people are even more easily identifiable as immigrants. As Karen (Paw-ka-yaw) and Hmong communities gain civil rights and yet sustain pride in their ethnicity, the idea of being proud of diversity takes root. National unity does not HAVE to mean cultural subjection. Finally, this is a timely seasonal reflection. For Christians, Advent leading to Christmas is a reminder of the intention to create a different kind of realm. Kingdom was a term of the era in which Jesus was advocating the things that now come under the heading of human rights and human unity. Political powers, kings and Caesar, were not going to do the job of valuing human life differently. Only a divinely inspired grassroots respect for diversity and inclusion have the potential needed.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed