|

On Christmas I “joined” the congregation of the Washington Cathedral for their midnight Eucharist at which the Episcopal Bishop of Washington DC, the Right Reverend Mariann Budde delivered the Christmas homily. It was inspirational, insightful, and interesting. It “worked,” I thought, reverting to my seminary-teacher mode.

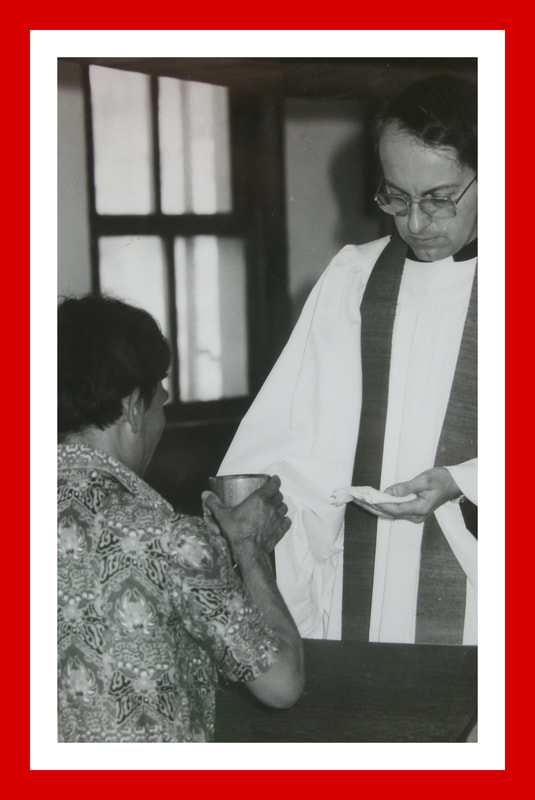

But why did it work? Why do some sermons work and others do not? This is a question I pose not only for Christian preachers but for Buddhist and other preachers, as well as those who listen to preaching. There is one absolutely indispensible component for a successful preaching event: the listeners must be imbued with the foundational narrative as it relates to their existential context. In this case, the congregation in the cathedral and on-line (as was I) must know the Christmas story and find it currently and personally important. There is a link the preacher must make between the story that people know and how it relates to what’s going on. As to the Christmas Story, we Christians have that memorized. We know it by heart, at least the outline. It’s about Mary and Joseph going to Bethlehem, having trouble finding lodging in the inn, birthing the baby Jesus in an animal shelter, shepherds hearing angels singing and visiting the holy family, and then three wise men (kings?) on camels seeing a star and coming to worship the new king they have read about, and then evil Herod trying to kill the baby but Joseph taking the family and escaping to Egypt in the nick of time. The story can almost be taken for granted, as long as the audience is familiar with it. Christmas worship can then safely include symbolic references to the basic story. A star hanging from the rafters of a cathedral or stuck on top of a Christmas tree needs little explanation. Plaster sheep or children dressed as shepherds fit into the picture. Songs create a familiar emotional tone. Nevertheless, there are levels of meaning that can be explored … or not. Many Christmas services and most other Christmas events do not explore very deeply beneath the surface. Oh, there is a predictable anguish about how the real meaning of Christmas has been diverted by Santa and by commercialism. We try to get back to that real story with our candles and carols. But if the story is to be successfully probed for deeper meaning (that is, if the sermon is to “work”) it must connect the dots between what happened in Bethlehem some 2020 years ago and what’s going on right here and now. Bishop Budde’s homily was a splendid example of how to do it. She began by reminding everyone of Dietrich Bonheoffer’s heart-rending Christmas letter from prison to his family. She mentioned, then, her main point, that there is always a gap between what is and what could be. We feel that keenly on Christmas, but Christmas addresses that, because Christmas is all about a growth of awareness that God dwells with us. The STORY, she reminded us shows this gap, and how God comes to us to deal with it. The gap is seen in ourselves where we know we are not as we could be. It is in our family circle where there are divisions. In our community life we are polarized – ah, now she is particularizing a social condition. At the end she expanded her application to the whole world. Her sermon was pastoral, befitting her office whose symbol is a shepherd’s staff. It was not prophetic, denouncing the causes of the gap, but persistently announcing the solution as the main fact of Christmas. When speaking to people who know the Christmas story, it is expected to go deeper into what it means that God has come among us. Christmas is the beginning point and the ending point of the Bishop’s sermon. It was the context and the content of the whole service and what had brought the congregation to fill the National Cathedral at midnight. The sermon “worked” because the issue of gap and brokenness which is both universal and particular is consistent with the Story as everyone thinks of it. “Yes,” we respond, “there certainly was a gap between what God was doing in Bethlehem and what the government was doing.” And there still is this gap between what God is doing with Jesus and what governments are doing. What would it be like to preach on Christmas to a congregation who did not have the shared narrative of Christmas instilled in their minds? I have done that. In that case the homiletical task is quite different. Without Christmas as the unifying context and without the Christmas story to build on, the elements of a typical Christmas remain fragmentary and attached to individuals’ random and diverse meanings. The dots stay mostly unconnected. Most preachers would probably begin by introducing the Christmas story. “Christmas is the celebration of the birth of Jesus.” The idea would be to expand the audience’s knowledge, in hopes that some would “catch” or remember something. Maybe the benefit would be bridge-building between the audience and Christians living nearby. Preaching a Christmas sermon to a non-Christian audience would be a long-shot. It is hard to make it “work” at a deeper level because the audience does not have “the foundational narrative.” It is the same reason that tourists in Thailand tend to miss the whole point of a Buddhist sermon. The narrative context is missing for them as well as the social context. A Buddhist sermon loses a large part of its purpose if the congregation does not imagine themselves to be an extension of audiences who gathered to implore the Buddha to tell them how to overcome suffering. A Buddhist preacher will be most successful if the audience is a cohesive community and the preacher is an integral part of it. Most Buddhist funeral sermons, for example, assume that the fundamental story is shared by everyone, and that what is needed is an interpretation of how to overcome the multiple anxieties that death arouses. Both the sermon and the funeral event combine to do that. It is not strictly necessary for a Buddhist funeral sermon to be intellectually stimulating, or even fully understood. Some sermons are mostly chanted in a way that the congregation simply knows “that’s good, it’s just what it’s always been.” Anxiety subsides. A Christian Christmas celebration works that way to some extent. It is not strictly necessary for there to be a sermon. A cantata or pageant can renew the narrative. The Eucharist is supposed to do that surpassingly. The sermon is only successful in a context of understanding. Life is messy, but there is help nearby. The whole worship event communicates “it’s going to turn out well.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed