|

Who gets to say whether “God the Father of Our Lord Jesus Christ” is the same as “Adonai Elohenu” of the Jews and “Allah” of Muslims? Who has the authority to mandate, permit or ban the use of any name for the god we are calling God? This is more than an esoteric theological question. It has pragmatic impact.

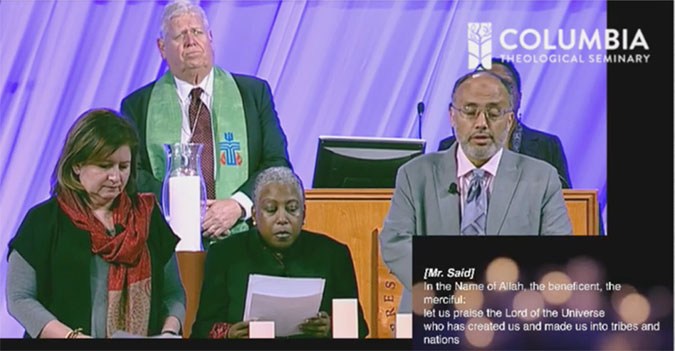

There is a sense of protective entitlement and ownership involved in this. People tend to get riled up when someone infringes on their right to say who their god is. It’s personal. But most of us become alarmed when our group’s god is described wrong. At that point it is a social issue. “You can’t call God Allah,” I was admonished not long ago. “Allah is not God!” At about the time I was being scolded in that way by a Christian who uses “Jesus” and “God” interchangeably, Muslims in Malaysia were going to court to prevent Christians from distributing Bibles that used the word “Allah” for God. Those Bibles were impounded. That’s pragmatic impact. Now we have the same debate in a distorted form being waged in public media by candidate(s) for President of the United States. Religion is playing a larger role in this year’s Presidential campaign than at any time since John Kennedy was running for office. Who speaks for God can be political. You may have an image in your mind of a god sitting serenely on a lotus blossom, or peering severely down from celestial clouds. It’s entirely up to you. If you share your view with someone, it’s up to the two of you. If you join a group and want them to adopt your concept, it’s up to the group. That’s the principle. Is God legitimately addressed as Allah? That involves a second principle, concerning discourse. It’s usually a matter of context. The trouble is that contextual boundaries are fuzzy. Just a couple of hours ago (as I wrote this essay) a controversy arose when someone at a Presbyterian gathering offered a prayer that mentioned God as synonymous with Allah. Protest came from those who refuse to countenance the idea that Muslims and Christians have anything essential in common. I will come back to this prayer later. First, consider contexts for discourse involving God-Allah. Prayer is one context. Can a prayer offered by someone in a public gathering contain names for God that some might object to? This is a frequently recurring issue wherever religious representatives are invited to lead public groups in prayer. I believe Christians have forgotten the principles of public prayer as opposed to private prayer. In public prayer someone articulates a prayer, and then the assembly responds with “Amen” if they want to. “Amen” is a word derived from the Bible in Hebrew that means one accepts the prayer as one’s own heartfelt prayer, too. Amen doesn’t mean “the end”; it means, “Yes, me too.” Amen is how one person’s prayer becomes the prayer of others. But the person leading a public prayer has an implied duty to respect the persons being invited to include themselves in the prayer. The prayer leader needs to try to respond to what the assembly is thinking, concerned about, and attempting to become. This awareness automatically contextualizes the prayer. It’s how the prayer leader involves the listeners cognitively, emotionally, and spiritually. Otherwise the prayer will fail to be in behalf of the people. But it is unlikely and unnecessary that a prayer leader compose a prayer that in all respects everyone is completely comfortable with. Speaking is also contextual. Talking and writing implies dialogue, even if the exchange is not explicit. A speaker before a group is in a “both-and” situation. The speaker is both a group representative and an independent individual – depending on context. Who the speaker represents may be as important as what is said. If the speaker represents a group, that needs to be made clear. H.H. Pope Frances said not long ago that Muslims and Christians pray to the same god (God and Allah, by name). As the acknowledged leader of a billion Roman Catholics he might have been speaking “to” or “in behalf of”. Speaking to, means communicating with. Agreement with what is being said is merely a hope. Speaking in behalf of, means that agreement by those being represented is assumed. Was the Pope’s statement a personal-pastoral one, or ex cathedra: formal-official? I think in this case he was advocating an understanding about God that he hoped all Christians and Muslims might agree upon. Language is also an aspect of context. When one is speaking in English in a Christian gathering, to refer to God as Allah makes a striking emphasis and probably an argumentative one. It is different if one uses the word Allah while speaking in an Arabic language. In that regard I wonder what the Muslims in Malaysia proposed the Christians call God, if not Allah. As I understand it the Christians said Allah is the word for God. The Muslims were trying to prevent the Christians from including themselves as Allah-worshipers, but they avoided proposing an alternative term. Conservative Islamic clerics might have been trying to head off such phrases as “Allah, the Father of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.” Hearing Christians pray to Allah is one thing, but hearing them re-describe Allah as Father of a second divine figure named “Lord and Savior Jesus Christ” would be too much for them to tolerate. Conservative Muslims object to Christians using the word Allah because they cannot abide the elevation of Jesus to divine rank. Conservative Christians object to liberal Christians using the word Allah because they think that by doing so Jesus must be demoted to the rank of prophet. But were the Presbyterians right to invite a Muslim to pray to God identified as Allah? As I reflect on it, the prayer leader had the right as the one chosen to pray. The assembly had the right to say Amen or to refrain from doing so. The prayer leader also had the right to expect Presbyterian support for a prayer to Allah, God. In the official Presbyterian Church USA Book of Common Worship,prayer 726 says this: “Eternal God, You are the one God to be worshiped by all, the one called Allah by your Muslim children, descendants of Abraham as are we. Give us grace to hear your truth in the teachings of Mohammed, the prophet, and to show your love as disciples of Jesus Christ, that Christians and Muslims together may serve you in faith and fellowship.” And to that I say, “Amen”. Note: The picture accompanying this essay is of Wajidi Said offering the prayer referred to above at the opening plenary session of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church USA in Portland, Oregon, June 22, 2016.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed