|

Sorry, friends, there is no such thing as inerrant scripture. If you are counting on a perfect Bible, it isn’t to be found. All we have are best guesses about what the Bible says.

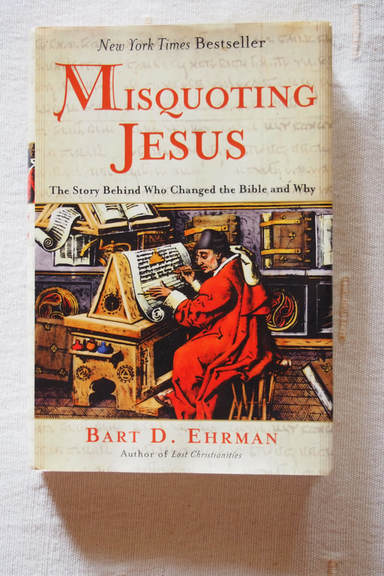

This could come as a blow to those who are convinced that every word of the Holy Bible is inspired by God and accurate. Even if a reader is not persuaded that the Bible is literally the day-to-day account of how God made the world and the step-by-step description of how it will end, it is hard to know what to believe if THE BOOK doesn’t tell us. Christianity is a “religion of the book” in a way many world religions are not. The book is where we start to decide every issue of theology and to evaluate every tradition. It seems that each generation has to acquire basic intellectual tools for itself. One set of tools is a system for deriving Christian truth. Since the beginning of Christianity as a church (that is, as a coherent organization) the starting point has been scripture. Step one, “What does the bible say?” Step two, “How do we decide what it means?” Step three, “What then is necessary for belief and practice?” In my day, seminary education tended to call those steps exegesis, hermeneutics, and systematic theology. As a practical matter our exegetical studies were limited to elementary courses in Biblical Greek and Hebrew, moving quickly to a few exercises in evaluating texts and translation. We learned that nowhere were there manuscripts actually written by Matthew or Moses, no songs by David or Solomon, and Jesus probably could not write at all. What we had were various editions of manuscripts copied from previous ones with some differences, one from another. But never mind, they BASICALLY agreed, and detectives had been working on finding out what were the most likely versions. Our Greek and Hebrew Bibles had immense footnotes to keep track of the important little differences between the old manuscript found in the Vatican Library and the older one found in the monastery in the Sinai Desert, for example. We held our breath for new twists coming out of the Dead Sea Scrolls at that time, and were relieved to find our versions being confirmed. We heard why the Gospel of Thomas was not in the Bible, but the books of First and Second Maccabees could be appreciated anyway. In effect, our exegesis course was about gaining confidence that we could rely on newer translations to have done a better job than older ones because the hard-working translation committees had access to recently discovered documents and they had the benefit of a vast amount of careful studies of the tricky bits. However, if the very idea of scholarly research is being doubted, as it seems to be these days, then another way of deriving Christian truth will be employed. Cue the preachers. One thing that anti-intellectual preachers have in common, in addition to disdain for the intellectual elite, is a short-cut to the truth. There is no need for tedious study of ancient texts because the Bible we have is just fine. There is no need for contorted discussions of what the Bible means because it means what it says. Ah, we have arrived back at the beginning where the question is, “What does the Bible say?” This generation, much in need of tools to debate how we can do anything in the face of such arrogant stupidity, can be thankful for help from Bart Ehrman of Chapel Hill, North Carolina. --------------------------------------------- Misquoting Jesus: the story behind who changed the Bible and why. Ehrman, Bart D. 2005. Harper Collins. This NY Times bestseller accomplishes what the author sets out to do. He presents a history of biblical exegesis that any non-scholar can understand, and he argues against biblical literalism on the basis that there is no fixed text and there never has been. His historical review is limited in such a way as to maintain the focus and avoid extraneous argument. He describes the exacting science of textual comparison. He selects various texts to show how some of the thousands of text differences may have happened. Most of them are trivial but some have had a profound impact on theology and history. Ehrman is not shy about mentioning how some of our most precious beliefs are founded on scripture that has been adjusted to enhance those points. Suspicious Biblical verses about the doctrines of the Trinity, the Virgin Birth, and the subordination of women are discussed. He concludes with observations about how interpretations are unavoidable. The Bible does not say anything that cannot be interpreted in various ways. But if you want to understand the Bible you have to understand how it came to us as stories, poems, legends, sermons that were never meant to be taken literally, word for word. Ehrman confesses that this is a lot easier when one realizes that we do not have a set of words that came directly from the mouth of God. --------------------------------------------- I am completely in awe of Bart Ehrman. He wrote his entire history and defense of the science of exegetics without ever once yielding to the temptation to mention the term. His writing is very much for people like my sister who never spent a day in seminary or college, but know as much about how the Bible functions in life as any of us and wonder what went wrong recently. What went wrong is that a way was invented of extruding what the Bible says without going to the trouble of questioning whether or not the Bible says it.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed