|

Essay #4 on SOCIAL ORDER

Expression vs. communication “OMG this is awful” she exclaimed in bright red letters on Facebook. That was it, no explanation of the exclamation. No clue about what was awful. Within an hour 20 friends were sympathizing mindlessly and wanting to know more. For a day she refused to reply. I began to wonder whether she was just getting a kick out of messing with us, but I think something was messing with her. Compassion aside, what she was doing was not communication, although it is what passes for it these days of communication deterioration. Internet Communication Technology (ICT) has changed the parameters of speech. Before: Expression was contained: private, personal, privileged Communication was conversational, conventional, conciliatory Media were moderated, managed, modulated Now: Everybody is the owner of their media The right to express is being aggressively asserted (under the banner of “free speech”) The effects of expression on communities (e.g. hate speech) are denied The difference between expression and communication is blurred How did we get into this loss of meaningful communication? Not surprisingly modern philosophers have dedicated a lot of their speculation toward the subject of communication. The move to consider language as the basic philosophical issue began with Bertrand Russell, of England. Bertie insisted, “a statement that purports to be about reality but whose truth or falsehood makes no observable difference to anything has no content, no meaning – it is not saying anything.” Only statements that are empirically verifiable are empirically meaningful; and the actual meaning of any given statement is revealed by the mode of its verification. The tool to sort this out is logic, a field in which Russell had excelled. For example, using logic, we can sort out the truth or falsehood of the following statements, and if we cannot, then the statements are meaningless.

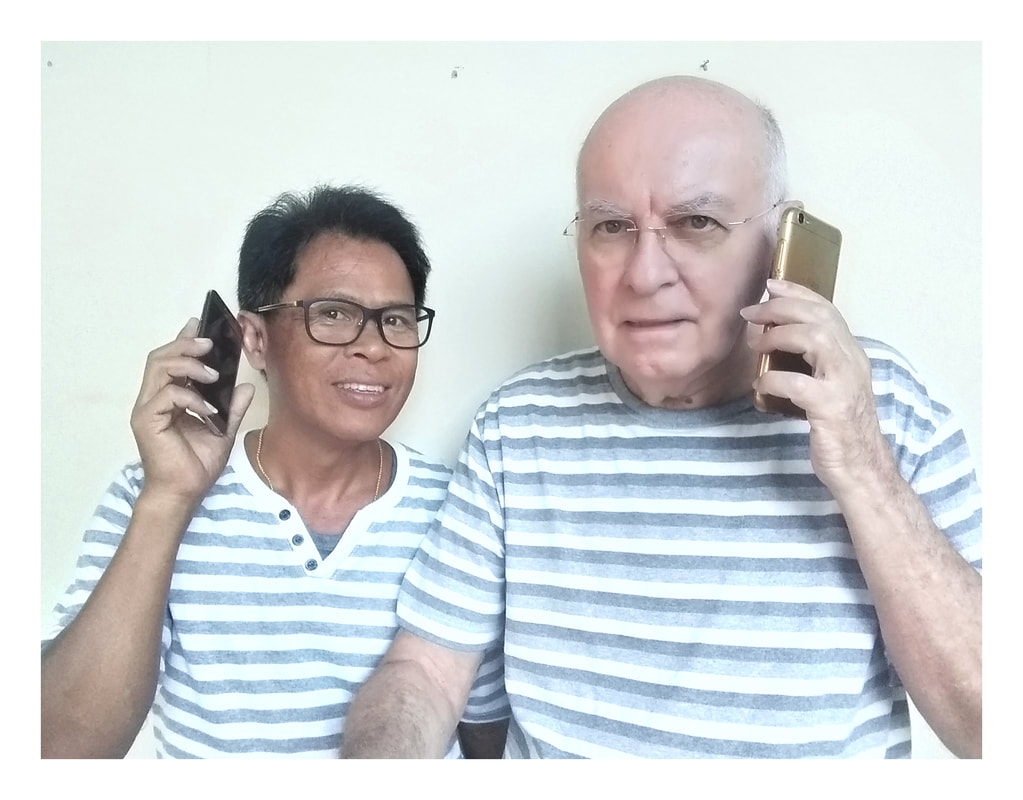

All the statements are in some sense false, but the reasons are different. The English throne is wooden, not iron (if by that is meant the “Coronation Chair with the Stone of Scone”). It is factually erroneous. There is no such thing as an American throne because the USA does not have any form of monarchy, so the statement is ridiculous. The Pope has a number of thrones, and any chair upon which he is seated is a throne if the Pope is performing official duties, but none of them are principally made of iron and, more importantly, the term “Papal throne” refers not to a chair but to the office. The throne in Kings Landing in George R.R. Martin’s books Game of Thrones, does not exist in reality and everything about the Iron Throne refers to a fictional object in a fantasy realm. However, within the realm of literature, the phrase would be true until the last episode when the throne was destroyed by dragon fire. The English throne can be metaphorically said to be made of iron, being durable as England is enduring. When an entity being discussed does not really in any sense exist, any statement about it is meaningless. This distinction was picked up by Ludwig Wittgenstein, Bertrand Russell’s student and successor as the major philosopher of England, having moved there from Austria when the Nazis took over Austria. Wittgenstein was renowned as the founder of the philosophical school of Logical Positivism, a rigorous type of analytical philosophy. What the Logical Positivists sought to analyze was not the logic that Russell thought to be the key to what can be said to be true or false, but the content of the words being used. Wittgenstein insisted that words have only the content assigned to them. Words mean what the users intend for them to mean. Moreover, words derive their meanings ultimately from whole forms of life. For example there is a whole world of scientific activity and scientific terms derive their meaning from the way they are used within the scientific world. There are whole worlds of military, political, religious, musical and countless other activities within which a term may have a specific meaning it does not have in another context. For example. “head” in the world of fresh produce draws to mind something like a cabbage. “I’ll take that head,” she said to the green grocer. The head of a social structure would be the appointed leader. “The chairman is the head of this company.” In the world of physical anatomy the head means a complex part of the body. “Use your head,” his mother shouted. Whereas, for a sailor, the “head” most commonly means the toilet. Logical Positivists rejected the idea that anything can be meant by a term unless its context is known, which provides the most important clue to what the term means to the person using it. Michel Foucault followed Wittgenstein and went a step further to propose that the reason people use terms, whatever their world of discourse, is that the user wants to manipulate or control the recipient. In fact all narratives do this, but mega-narratives do it in a mega-way, by which those with social power seek, through the invention of stories and myths, to extend their influence and control. Foucault advocated the deconstruction of those cultural artifacts, and insisted that the smaller the narrative the less it needed to be mistrusted. Foucault’s discursive analysis theories have the potential to revise the major political structures of the Enlightenment. At the same time the post-structuralist movement, until recently called post-modernism, has become the prevailing tone of voice of our times. Installing doubt about the intentions of all speakers -- without a positive counter-force -- has led to cynicism and a “me-mindset.” Doubt has morphed into suspicion and fear. The fragmentation of empires has led to the break-down of nations, the establishment of enclaves, and the embellishment of protectionism by ever-smaller socio-cultural units. Enter the era of EXPRESSION rather than conversation. If all words are contextual and infected with manipulative intention, the words do not contain anything that matters. What is left are effusion, expostulation, and effect. That is now amplified by the development of technological ways of storing data and disseminating it. The local newspaper gave way to television which then relinquished its main purpose of broadcasting information in favor of entertainment. Even the “news” must be entertaining. Newsmakers must be valuable as attention-grabbers. Boring politicians is an oxymoron, or will be at the next election. Absurd and ludicrous are preferable to bland and rational. ICT has made possible hundreds of “channels” of TV, and every individual with a smart phone can be a producer. In the domain of private discourse, too, meaning is not validated by content having a specific, consistent reference. Children learn this as an early survival strategy. Crying from hour one is just expression. By about day one it becomes more often expression of felt need. By year one the clever child has developed diverse ways to communicate felt needs. By year ten, mother, too, has acquired (or remembered from ancestors) skills in which “it’s not what she says but what she means.” “I’ve made your favorite dessert,” she says; but she means, “Congratulations on making it through that difficult patch, or passing that landmark.” Threats, as well, rarely mean what they say. So we grow up and move on to become part of the social order. We belong to different groups, and we mean different things in each one. It can be confusing. It tends to be challenging. It can, at times, be exhilarating to be Grandpa in one context, pastor in another, community elder just outside the gates, and author of essays. As we grow toward senility, or at least some form of advanced aging, we have more stories to tell, but they mean less and less. Once, our story might have suggested a course of action. Then later, that same story could have been a cautionary tale. Now it is a nostalgic recitation. But for every listener in this time in which we live, the task is to sort out what is true from what is meaningful. That is how our social order is kept from destroying itself and from deteriorating into irrelevance.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed