|

“Woke is a political term originating in the United States referring to a perceived awareness of issues concerning social justice and racial justice,” our amazing online reference resource, Wikipedia, informs us. “It derives from the African-American Vernacular English expression ‘stay woke’, whose grammatical aspect refers to a continuing awareness of these issues.”

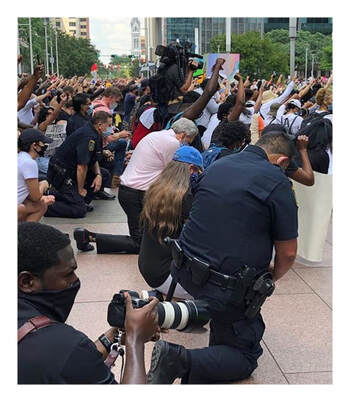

I’m guessing a few million of us became aware of the word “woke” during the events following the murder of George Floyd when protests arose and expanded from anger about that single injustice, to that sort of injustice, to what police do, to the danger of white supremacy, to the racism of some national heroes (Columbus, Churchill, Woodrow Wilson, Gen. Paton, Robert E. Lee … and Edward Colston – you’d know who he was if you were a woke Londoner). The protests were a “Woke Movement”. The question that quickly follows when one is woke is what to do about it. And that sometimes leads to our second jargon of the year Cancel Culture. “Cancel culture refers to the popular practice of withdrawing support for public figures and companies after they have done or said something considered objectionable or offensive. Cancel culture is generally discussed as being performed on social media in the form of group shaming.” Thanks for that definition, Pop Culture Dictionary. Before this year I would have associated the term with, say, a TV show being cancelled when the ratings dropped. Then came the ruckus about J.K Rowling, the author whose books I have read and written about more than any other in the last 20 years. Timorously, a group of alarmed celebrities (including Piers Morgan of the BBC’s “Good Morning Britain”) have tried to help us understand that cancel culture attacks can become exaggerated, as when a group of Vegans intruded into a British steak restaurant and interrupted everybody. They were out-shouted by a spontaneous group of diners chanting “Red Meat, Red Meat!” As I understand it, social media (and by that many observers mean TWITTER) have raised the stakes. For some targets, such as Rowling with her millions of pounds in the bank, being smeared and vilified online and having her popularity dimmed is more of an inconvenience than a danger. But for people of lesser means, just being accused of not being a strong enough supporter of a cause can result in the end of a job or being physically attacked. Stay woke, cancel culture, and virtue signaling, which are moral issues, have a sinister potential to turn into a purity spiral, which is a competition. Nathan Taylor, a gay guy who loves knitting started a hashtag aimed at promoting diversity in knitting. What happened was what Gavin Haynes in a BBC documentary called a “purity spiral” in which the online “discussion” intensified into moral outrage. Haynes insists that “the spiral often concerns morality, it is not about morality. It’s about purity — a very different concept. Morality doesn’t need to exist with reference to anything other than itself. Purity, on the other hand, is an inherently relative value — the game is always one of purer-than-thou.” What happens is that people who are involved feel the need to defend their purity as more pure than other’s. They list examples. The knitting group began talking about the books they were reading to prove they were pure of the racism the knitters were being accused of. The books were found to be racist by other knitters. Knitting businesses began to become targets. But those accused could also benefit by agreeing with the thought leaders. Saying, “We just sell yarn!” could lead to death-threats. But agreeing that “We knitters have been deeply remiss in our failure to acknowledge the pain we have inflicted on struggling Black and indigenous people of colour,” [a paraphrase of a comment by a Scottish knitter quoted by Haynes] might get one by until rants began that “just feeling sorry is the very essence of white privilege.” When Nathan Taylor tried to calm things down the attacks intensified so much that he had a nervous breakdown. Purity spirals can have those outcomes. They happen when a purity spiral turns mindless and destructive. But purity spirals contain their own demise in the way they form. Pressure to be purer and purer leads to posturing and defensiveness that are unsustainable. Timur Kuran, Professor of Economics and Political Science at Duke University, calls this ‘preference falsification’. His theory relates to things like the fall of the Soviet Union, where almost no one saw the end coming, because they hadn’t realized that an entire population was falsifying their experience to each other. That’s what happens when one tries to win in a purity spiral. Eventually the effort simply becomes too much. Before that happens it can get very ugly.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRev. Dr. Kenneth Dobson posts his weekly reflections on this blog. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

| Ken Dobson's Queer Ruminations from Thailand |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed